MIT HSSP and Stanford Splash! by Anna H. '14

Seven fundamental questions, and a field trip to the west coast

At MIT, I’ve taught for two Splashes, three Sparks, and two HSSPs. My classes have evolved with my interests:

- Spark (Spring 2011): Rockets and Composites (how rockets are designed and built)

- Splash (Fall 2011): Senses and Sense-abilities (the neuroscience behind the five senses)

- HSSP (Spring 2012): Introduction to Cosmology

- Splash (Fall 2012): Introduction to Radio Astronomy, Introduction to Pulsars

- Spark (Spring 2013): Introduction to Radio Astronomy, Introduction to Pulsars

- HSSP (Spring 2013): The Evolution of Our Scientific Answers to Seven Fundamental Questions

MIT is not the only school with Splashes. It does have the biggest Splash, but Stanford has the second largest, with over 1800 students taking classes from Stanford students. Yale, Columbia, Duke, Rice, Boston College, Clark University, Princeton, U. Chicago, all have Splashes (and those are just the ones I’m aware of.) We want Splash programs to learn from each other, so we send representatives from one Splash to another to help out, see how they function, and give them suggestions.

At the end of February, Chelsea V. ’15 and I received an e-mail saying “You’ve been selected to travel to Stanford Splash! Let me know if you’re still available that weekend and are still interested in traveling” – and on Friday April 12 (the last day of CPW :( ) Chelsea and I boarded a plane to San José. We were hosted by one of the Splash coordinators, who’s an MIT alum (actually, it seems like a LOT of the people involved with Stanford Splash are MIT alums…to the point where most of my dinner table was wearing a brass rat.) Saturday morning, our alarms rang at 5:30, so that we could walk over to headquarters and help set up.

I taught two classes that afternoon: a pulsar class for parents, and a pulsar class for middle school kids. The next afternoon, I taught a pulsar class for high school kids, and three radio astro classes: middle school first, then high school, then parents. My friends Sameer (a junior at Stanford, who went to middle and high school with me) and Daniel (a chemistry grad student at Berkeley, and MIT alum) came to my last class, which made it extra exciting.

The most obvious difference between Stanford’s Splash and MIT’s Splash: Stanford Splash encourages people to go outside. They have umbrellas to block the sun. They actually set up tables under those umbrellas. It was totally mind-boggling. This whole “weather in which you can actually stand in lines outside” is not something MIT ESP is used to working with. Something else I’m not used to working with: the overwhelming scent of trees and flowers, everywhere. I admit that it was a little painful to return to Boston after that.

The weather was fabulous, but my favorite part of the experience was seeing how very similar the people involved with Stanford Splash are, to the people involved with MIT Splash. Undergrads and grad students excited to teach. Kids excited to learn on a weekend. Parents a little frantic, but driving in from all over the place, dead set on their kid taking all the classes he or she wants to take (trust me: I spent two hours working at the desk that parents come to when something isn’t right with their kid’s schedule. It was busy.)

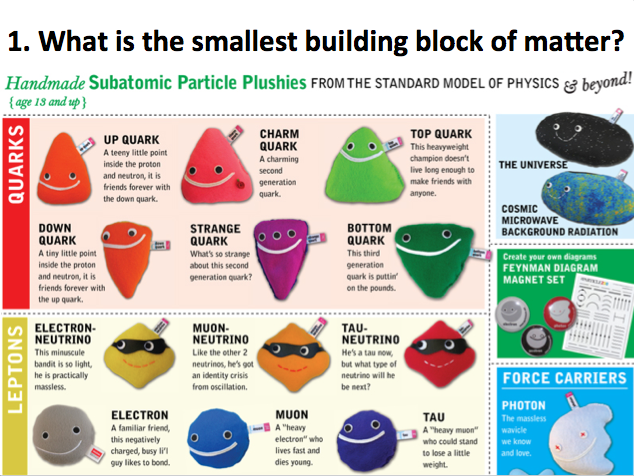

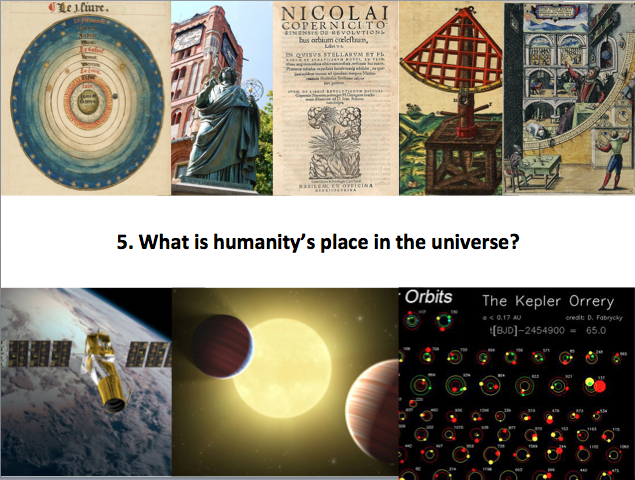

Back at MIT, my attention returned to HSSP. This spring’s HSSP class was a challenge; my friend Eric ’14 and I tried to think of seven questions that every civilization in history has had a working answer to. “How did the universe begin?”, for example, and “where did life come from?” We spent one class day on each of those questions, and talked about how answers have evolved over centuries and millennia. We presented a tentative “this is what scientists think right now” for each question.

Questions like “what is disease and how can we cure it?” and “where did life come from?” meant that I ended up lecturing on topics totally outside my comfort zone. I borrowed biology textbooks from friends, did an intense amount of Google-ing, and prayed that I wouldn’t make a fool out of myself in the classroom. It was sort of like having to do one research project per week, which was very time-intensive; it worked out fine, though, since we were presenting the topic at a very broad introductory level so didn’t have to worry too much about our non-expertise in evolutionary biology and pathology and what have you.

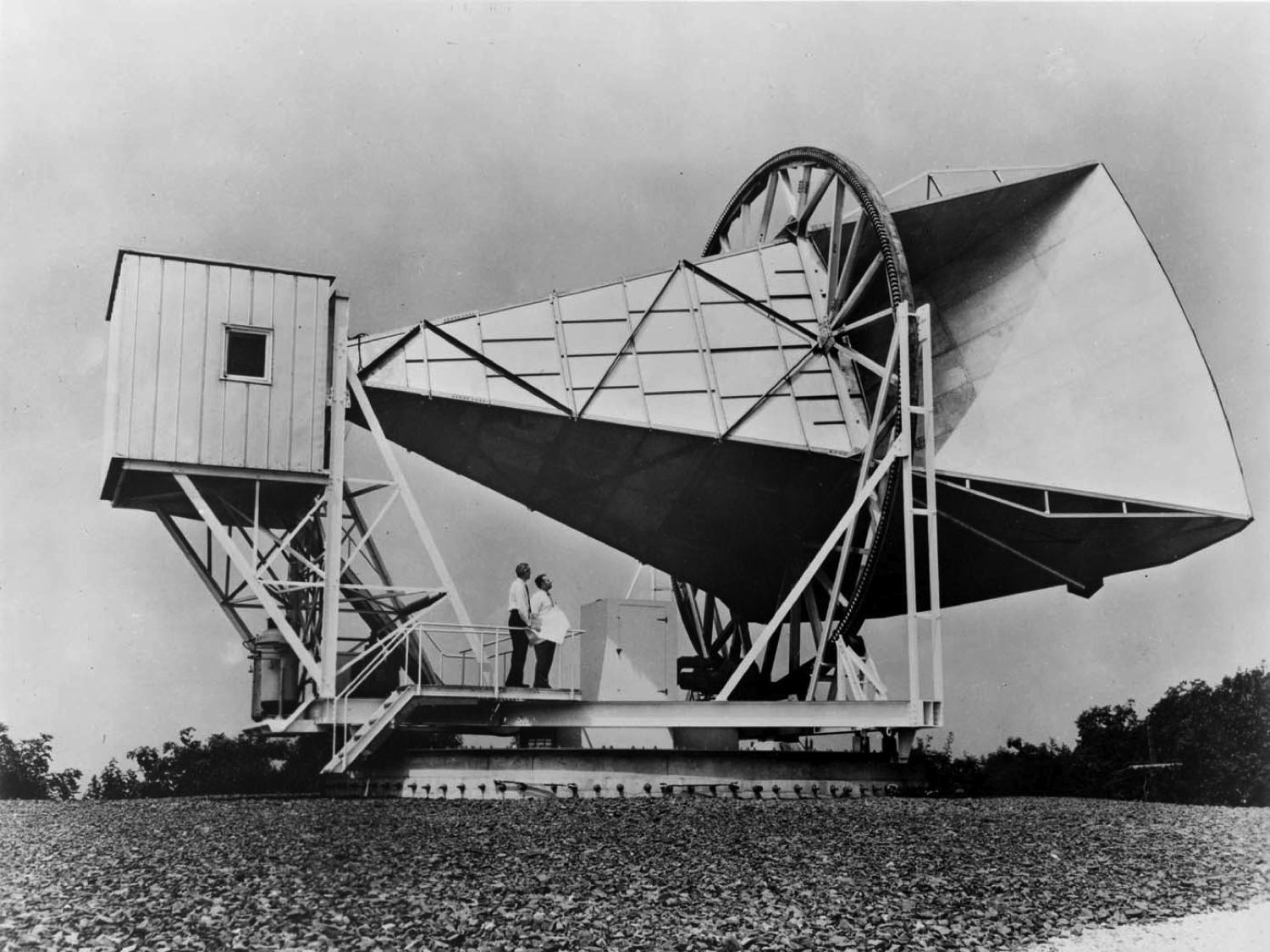

On the last day, I found an excuse to squeeze in some radio astronomy (a topic I *actually* know about) – I showed the kids a picture of the horn antenna that Robert Wilson and Arno Penzias were using when they discovered the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation. The story of that discovery deserves a lot more than a few sentences, but spacetime is limited, so bear with me. Penzias and Wilson were doing radio astronomy in 1965, which means that they were using a giant antenna to detect radio waves from space. The bane of a radio astronomer’s existence is “noise”, or “interference” – extraneous signals from the instrument, the atmosphere, the ground, civilization, etc – so Penzias and Wilson were trying to carefully subtract all those effects from their data. They noticed that there was a background signal, that persisted no matter what direction they pointed their telescope in; they determined that it was not due to their electronics. Anyone’s best guess: pigeon poop! The telescope was dismantled, the pigeon poop cleaned out, and the instrument restored. Signal remained. Eventually, they figured out that it was actually the oldest signal ever detected: an afterglow of the newborn (370,000 years-ish old) universe.

I showed the class this picture of the horn antenna:

Now, I saw a horn antenna in person last summer, and don’t remember being particularly aghast by its appearance. But the kids FREAKED out – “AHHHHH!” and “WHAT IS THAT THING????”

And that was nothing compared to how they responded when I showed them this picture of it:

They screamed louder. “IT CAN TURN????” “WHAT IF IT FALLS ON THEM?????” They were totally flabbergasted that such a gigantic bizarrely-shaped thing has ever been constructed by humanity, let alone used for science, let alone used for Nobel Prize-winning science.

That moment was priceless. One of the best parts of teaching: students’ reactions remind you to step back and appreciate familiar material with a newcomer’s eyes.

Another priceless moment, during Spark this spring. 20 minutes into my hour-long pulsars class, an MIT student walked into the room, brandished a piece of paper, and informed me that he had this room reserved.

Ummmm. No?

I asked him to go talk to the Spark admin team, down in their office. He disappeared grudgingly. Two minutes after my class ended, he returned with an ESP admin; turns out that ESP made a mistake, and this kid actually did have the room reserved. I was supposed to have it for the whole day, so that was awkward. I was re-assigned one of the only empty rooms left (well over a thousand kids come to Spark) which had just about enough room for one big square table and ~10 chairs.

There were 40 kids signed up to take my afternoon class.

In a frenzy, I spent about half an hour dismantling the table and piling the pieces at the front of the room, so that the kids could all sit on the floor. I put the projector at the back of the room, and got Eric to sit back there and hit “next slide” for me. To teach, I stood on the table fragments at the front of the room, and projected my voice over the kids who were piled on the floor. I nearly fell off, once or twice. It was totally chaotic. But memorable.

I’ll end this post with the ending to my HSSP class. I put the six (seven became six, because one class was cancelled due to all the violence in Boston) fundamental questions from the semester on the projector, and assigned one pair of kids to each question. Eric and I kicked back, and let our students teach us what they learned.