Writing is useful for science. by Anna H. '14

Surprise!

Sometime last year, a prospective student e-mailed me asking about the pertinence of writing to science.

The answer was: writing is an absolutely essential skill for a scientist.

* * *

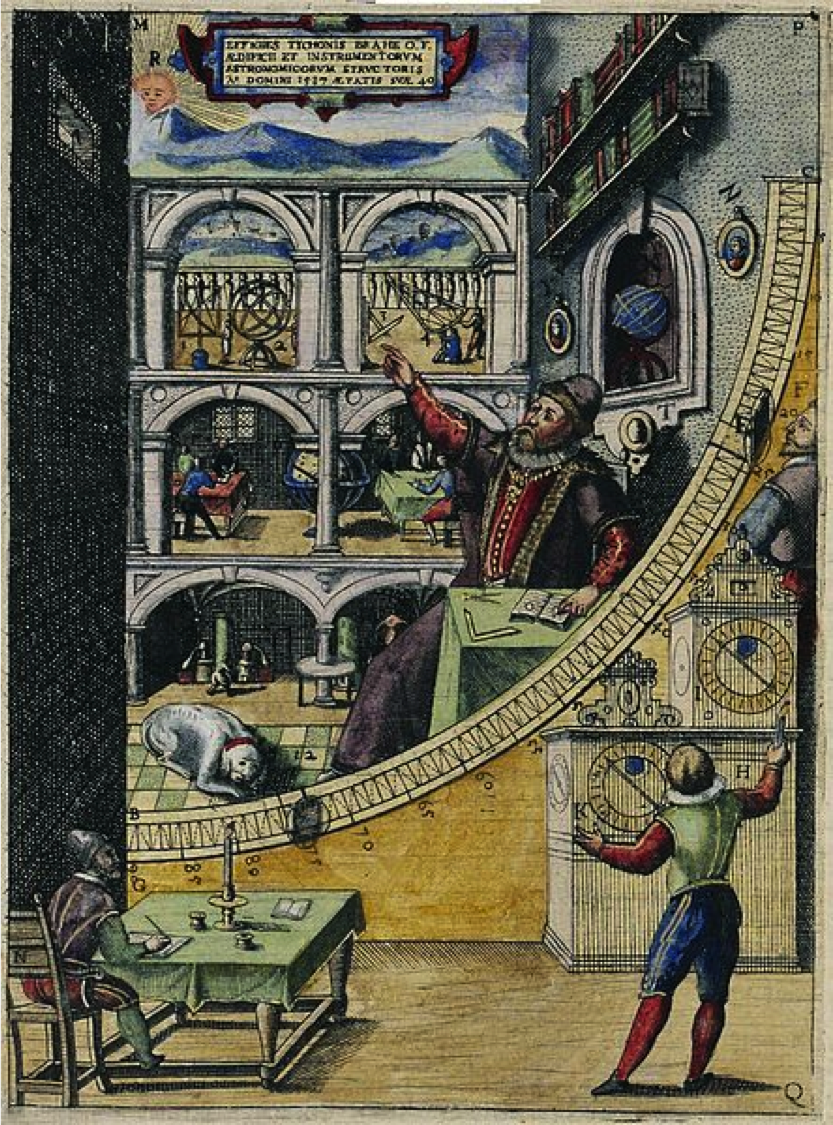

The days of partyboy/astronomer Tycho Brahe reclining in the quadrant he built into the wall of his palace are (regrettably) over.

|

Professional astronomy rarely involves sticking your eye through a telescope. Professional radio astronomy – my kind of astronomy – never involves sticking your eye through a telescope; your eyes can’t see radio waves! Nowadays, astronomers apply for “observing time” at a gigantic expensive telescope like Chandra (x-ray), Keck (optical), Spitzer (infrared), and the Very Large Array (radio). Some of these facilities are open to anybody, and some only open to certain communities (universities, etc) — some have a particular amount of time allotted to X Institution, but the rest is open to the general public. So, if you knew what you were doing, you could in theory get observation time on the VLA.

I say “in theory,” because as you can probably imagine, getting time on one of these telescopes is competitive. There’s only one ALMA, for example, and a zillion astronomers who want to collect data with it; during its first round of data collection, ALMA was over-subscribed by a factor of 9 to 1.

How do you get time? You write. You argue persuasively for why YOUR project is important. You describe exactly how much time you need, exactly where you want to look in the sky, what frequency you want to observe at, what bandwidth, what signal-to-noise ratio you expect, and why all of this means that you will be able to get the scientific results you want. A committee of other astronomers read over your proposal very critically, and evaluate whether it deserves telescope time. If you wrote a strong proposal, and get time, then at some point during the observing semester the telescope will look at your object(s) for the length of time you specified; and the data will be made available to you electronically.

There are comparable demands in almost all scientific fields: writing grant proposals, etc. So, for all you scientists-in-training who hate English class and dream of the day you never have to write another essay for anyone ever, sorry. It doesn’t go away. You will always need the skill of communicating – and persuading – through writing.

For many astronomers I know, writing proposals is a huge pain in the butt; it’s one of those things that you just HAVE to do as part of your job, because that’s the way the field works. I love writing papers as much as (if not more than) I love writing code, however – and this makes my life awesome.

* * *

NRAO summer students (those based in Charlottesville or Socorro) are the lucky recipients of 2 free hours of EVLA time, and 4 free hours of VLBA time: that’s free time on two of the most powerful interferometers in the world. That said, 2-hour, 4-hour blocks are pretty short, so not all of us can submit proposal ideas. Individually or in teams, we put proposals together (abbreviated versions of the real thing), present our science case to the whole group, and the summer student coordinates pick a few projects that they think are particularly appropriate for the short time span (bearing in mind that we only get a few days to reduce the data). In mid-July, the Charlottesville summer students fly down to Socorro, tour around the EVLA, and work with the Socorro summer students to perform the analysis and write up the results.

Usually, this is what happens:

* * *

On November 29, I got a *REALLY* long e-mail from “[email protected]” that contained two paragraphs of criticism about my proposal, a “linear-rank score” of 5.74, and an explanation that this is on a scale of 0 (outstanding) to 10 (very poor). I was mortified. I didn’t want to scroll down, and read the “NO TELESCOPE TIME FOR YOU!” section of the e-mail. I read that I had received “Priority B,” whatever that meant; finally, I got the guts to scroll down and found out that B means that the observations will be scheduled on a best-effort basis. I still had no idea what that meant, but it sounded like a polite way of saying “nope.”

At the AAS conference in January, I talked with a bunch of the NRAO astronomers, who looked astonished and excited when they heard my news and told me that Priority B was good, and that I was almost certainly going to get time. A couple months later, I got an e-mail saying that the telescope was all set to go ahead and observe my source. Of course, science is science and it turns out that some of the software wasn’t (and isn’t) ready, so I have to wait until the end of this month for it to be observed. But it will be observed, and then I will have a beautiful observing project with “Principal Investigator: Anna Ho” written on it — which is just the coolest thing ever. And all for volunteering to write an essay!

* * *

August 1 is the deadline for proposals. It’s nearly midnight, July 30. I have a day left. I’m writing a new proposal: this one is to look at a pulsar wind nebula called 3C 58. This is another product of a summer student observing project: this one actually won summer student time, but our analysis didn’t work out because we weren’t in an ideal configuration, and only had one hour of observing time. Now, in D configuration, we’ll be able to resolve the structures that we couldn’t see last time. This one is more fun to do than last year’s, because I’m working closely with a couple of other summer students. It’s also less fun to do than last year’s, because it’s more complicated and I’m having a much more difficult time figuring out what technical specifications would be ideal for our project. I got sick of writing the proposal by this evening — so, instead, I wrote a blog post about writing proposals. And now that I’m done with THAT, I have no more excuses.

But hopefully, come November, there will be an e-mail saying that my friends and I get to be co-investigators on a real EVLA observing project — with time that we earned by writing our own proposal, from scratch. There’s something beautiful and direct about that, almost like I can stick my eye to a telescope and look at 3C 58 myself.