10,000 Ways That Won’t Work by Andi Q. '25

“So, Andi, let’s talk about your accomplishments from this semester. Was your research output impactful enough to lead to a start-up?”

I just sat there and shook my head in silence.

“No? What about a publication in a peer-reviewed journal? Or at least a patent? I know MIT kids like you love inventing cool new things.”

Again, I had nothing. Trust me – I would’ve loved to have either of those things, but my semester just didn’t shake out that way.

“Come on, at least tell me you presented at a conference or to the EECS department at large.”

What would I have told them? That my experiments didn’t work? That the effect I investigated is likely not experimentally realizable?

“So what exactly did you accomplish then? You know this question is required, right? Whatever, just make up some other thing.”

Of course, this was not a real conversation with a person at MIT, but rather me filling out a particular section of the semesterly UROP evaluation form. And so, with the same regret I’ve felt the previous semester, I checked the “Other” box and moved on to the rest of the form.

What is a UROP anyway?

A UROP – Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program – allows MIT undergrads like me to collaborate with renowned MIT faculty on cutting-edge research. Typically, a student would find a lab studying an area of interest and work on a project alongside a grad student or postdoc while the UROP office or the lab funds their research.

UROPs are wildly popular, with 92% of undergrads doing one at some point. Understandably so – students gain technical expertise and research experience while labs benefit from the (effectively free) labour of highly-motivated undergrads; overall, a win-win situation for everyone involved. Additionally, many UROP projects sound extremely cool – who wouldn’t want to work on laser-induced mind control at MIT?

But probably the most enticing part of doing a UROP (at least for me) is the prospect of applying the skills I learned in classes to create a tangible product. Did you know that Collier Memorial outside the Stata Center was designed and built, in part, by UROP students? And that iRobot01 The company that makes Roombas. was partially the product of a successful UROP experience? And just a few days ago, Kathleen ‘23 had her research published in Nature and featured in MIT News!

Unfortunately, my UROP experiences thus far have not been nearly as successful as the ones listed above. I’ve been with my current lab for the past two semesters. In the fall, I fabricated magnetic memory devices using two exciting new materials, only to discover that they didn’t work because the crystal structures were incompatible. And in the spring, I tried to simulate a hypothetical physical effect that never emerged in the dozens of experiments I tried over the semester.

And it feels a bit disappointing

At MIT, I’m surrounded by incredibly successful people with incredibly successful research projects. I know students who discovered a major security flaw in Apple’s content recognition system as part of an MIT class project and presented their findings at CVPR02 The world’s largest conference in computer vision. . Some of my peers have even published research while they were in high school! And not to mention those professors with scientific results named after them while they were still undergrads.

These people pour enormous amounts of effort into their work and don’t go around boasting about their successes03 Obviously, there are exceptions, but this is true for almost all of MIT. . However, I still see news articles about MIT students discovering remarkable new technologies every other day. I deeply admire these people and strive to work as hard as them… yet sometimes I can’t help but wonder – what are they doing right that I’m doing wrong? Why do so many people have posters, publications, and/or patents to showcase their UROP work while I only have experiments that don’t work? Am I just bad at doing research?

In some ways, the answer to that last question could be “yes”. I initially struggled to understand things in the lab because I started the UROP without knowing any quantum mechanics, and I didn’t spend as much time in the lab as I should have because I was overcommitted in the past two semesters. Because of that, I worry about how those around me, like my UROP mentor, my lab’s PI, and my peers, would judge me. With MIT providing me with such amazing resources and guidance, I was afraid of being seen as incompetent; unable to get any of my experiments to work.

My insecurities are amplified further by the UROP evaluation form and a few people at MIT I’ve interacted with who make it seem like getting publishable results out of UROPs is the norm. “Oh, just publish a few good papers in your field.”, I recall one professor commenting when I asked about graduate school admissions, “That shouldn’t be too hard for an MIT student like you.”

Sometimes, I feel like I’m also a part of this problem. As an associate advisor04 A student who provides academic support and resources to first-year students. , I’ve given talks to bright-eyed first-year students about how to make the most out of a UROP. While I lectured about the importance of being proactive and a creative problem solver, I couldn’t help but feel guilty that I often failed to follow my own advice.

But that’s just how a lot of UROPs go

Upon further reflection and talking with some of my professors from this semester, I’ve realized that my research experience is surprisingly common across the undergrad population. It still kind of sucks that I didn’t quite advance humanity’s scientific knowledge as I’d hoped, but I feel considerably less bad about it now.

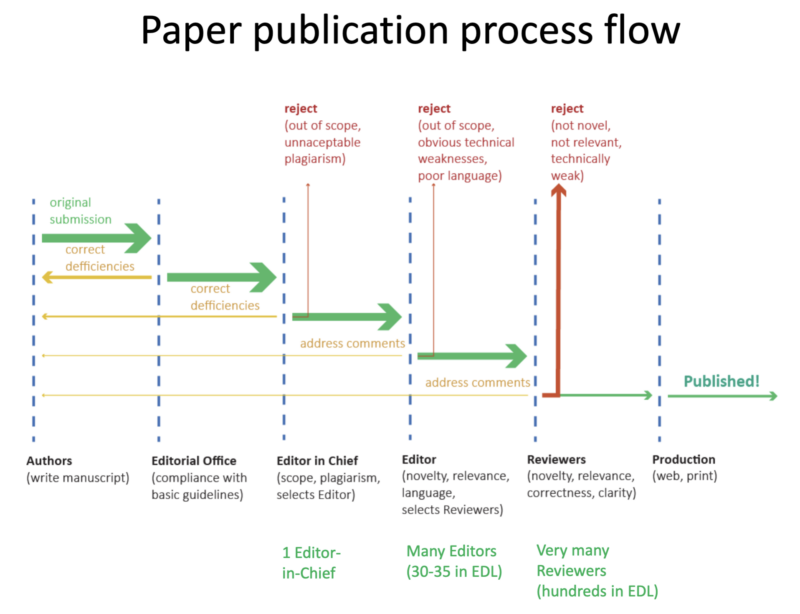

Firstly, most students who do UROPs do not get to publish their results either; the stuff I see in the news is the cream of the crop in undergrad research. After all, the publication process is long and arduous, as I learned in my communication-intensive classes this semester, so huge kudos to all my peers who have published before. (The numbers reflect this too – MIT publishes fewer than 2000 science papers annually, with grad students and professors accounting for the vast majority of MIT’s academic output.) All this to say that getting a publication out of a UROP, especially at my level, is probably not a realistic goal to set in the first place.

The publication process, as described by a professor in 6.2600 (micro/nano processing tech).

Secondly, it’s okay if things don’t initially work in research. When I showed my results from this past semester to my UROP mentor and PI, they were unexpectedly pleased with my work even though my simulations hadn’t worked as I’d hoped. As they explained, the insights we gain from knowing what doesn’t work are just as important as knowing what does. For example, my simulations taught them to avoid using permalloy05 The magnetic material I was using in my simulations. in their real-world experiments. The nanofabrication class I’ve previously written about did a great job of teaching me this lesson. In preparing us for research in microelectronics, it’s one of the very few classes at MIT where the final project doesn’t have to work to be considered successful. Although having a functional end product was satisfying, I learned much more from messing up intermediate steps and then reflecting on what went wrong.

(As an aside, I think it’s rather unfortunate that researchers don’t publicize their experiments that didn’t work, because others will ultimately try those same experiments and obtain the same results.)

But most importantly, I still managed to achieve my main goal for the research experience – to learn about nanofabrication and magnetic computing devices. Sure, travelling to conferences and publishing a paper would’ve been nice, but I believe the whole point for many UROPs at MIT is to learn research techniques outside of classes and gain exposure to exciting new fields. (And plus, I still have at least four more semesters left at MIT to get something to work!)

A happy ending after all

I must confess that up until now, I’ve been slightly misleading about the UROP evaluation form. The part I showed in the introduction was the only part of the form I disagreed with; the rest contained valuable questions to help me reflect on my experience and plan for future semesters. For example, the evaluation form emphasizes the importance of setting goals and expectations at the beginning of a project, which I’ve found immensely helpful for planning this past semester’s project.

Although the results of the past two semesters have been somewhat disappointing, I think it’s good to experience disappointment this early in my career before I start doing research full-time. Thanks to my UROP experiences, I now have much more realistic expectations about academia. I also learned a lot about what kind of work I want to do in the future; for example, although computational work allows me to get results much more easily and quickly, I still find experimental work more interesting.

Despite the disillusionment that often comes along with them, I find that UROPs really do live up to their names – opportunities for undergrads like me to do research, not only on cutting-edge technology but also about their personal preferences.

- The company that makes Roombas. back to text ↑

- The world’s largest conference in computer vision. back to text ↑

- Obviously, there are exceptions, but this is true for almost all of MIT. back to text ↑

- A student who provides academic support and resources to first-year students. back to text ↑

- The magnetic material I was using in my simulations. back to text ↑