Birds Are Real, and So Is Quantum Physics by Andi Q. '25

Monkey see, monkey believe

I believe in quantum physics now.

The past few weeks have changed the way I look at the world. Experiment after experiment has confirmed that quantum phenomena, as absurd as they seem, are real. And for once, I was able to see these phenomena with my own two eyes, in the flesh, because I was the one to perform the experiments!

I performed all these experiments in 6.2410 (Quantum Systems Engineering Lab) – a class I’m taking this semester to convince myself that quantum physics is real. 6.2410 is all about two things: demonstrating the fundamental properties of quantum particles and using those properties to engineer sensors that exceed “classical” (non-quantum) limits.

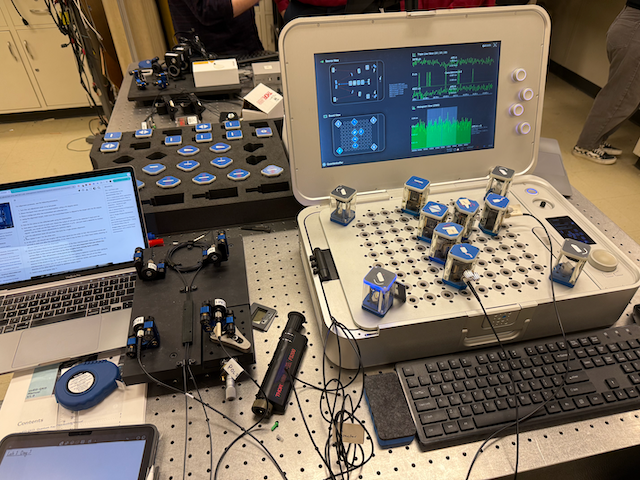

Most of the experiments in 6.2410 use quantum optics – think lasers, mirrors, and whatnot. Except instead of the $5 lasers and mirrors you can find on Amazon, we use the “Quantenkoffer” – a $500k quantum optics toolkit from Germany with nanometer-scale control over laser/mirror alignment.

This thing costs as much as many of the tools in MIT.nano, and they let me (a clueless undergrad) use it!

It might sound like overkill, but it’s not. One of the most annoying things about working with quantum optics is that experiments are unbelievably sensitive to alignment, so even a tiny misalignment (e.g., from breathing too hard on your equipment) can throw off the entire system. (Ironically, this sensitivity is what makes quantum-enhanced sensing so useful in the first place.)

The Quantenkoffer handles most of this tricky alignment process for us and dramatically speeds up experiments. Instead of placing the optical components in “free space” (as in a traditional optics setup), there are fixed slots where the components snap into place like LEGO bricks01 It reminds me a lot of the Rube-Goldberge-esque games I enjoyed playing as a child! Something about placing things into grids is just so oddly satisfying to me. . It’s not perfect and we still spend an hour each lab session aligning everything, but the instructors told me each experiment we do in 6.2410 (around two hours each) can easily span an entire semester at other universities without the Quantenkoffer.

We’ve worked with four different quantum effects so far:

- Entanglement.

- Single-photon interference.

- Two-photon interference (the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect).

- Photon antibunching (the Hanbury-Brown-Twiss effect).

The fact that these effects are real at all was mindblowing. (If you’ve ever seen a video of a monkey reacting to a magic trick, that’s exactly how I felt during the experiments.) But even more mindblowing was that people have found ways to apply these effects to solve real-world engineering problems!

So bear with me as I attempt to tell you about these effects and what makes them so weird.

Entanglement

Quantum entanglement is when two particles are correlated in a way that measuring one immediately gives you information about the other, no matter where it is.

In 6.2410, entanglement primarily appears as polarization entanglement. Polarization is a property of light that, for simplicity, we can measure as an angle between 0° and 90°. The Quantenkoffer has a laser that generates two photons at a time that are polarization entangled, meaning they are always both 0° (horizontally) polarized or 90° (vertically) polarized. This sounds impossible – how can we control individual photons with such precision? – but we verified with cold, hard measurements that this was indeed the case.

I honestly still don’t know how entanglement works. It feels like it just… happens sometimes. But I think most people don’t understand how it works. Even Einstein didn’t believe in entanglement in his day, and the (recent) 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded “for experiments with entangled photons”.

Entangled particles are the basis of many quantum technologies today, such as:

- Sensing: The classical sensing limits I mentioned above are usually due to unavoidable environmental noise. However, we can exploit the correlations between entangled particles to overcome these limits, because statistical correlations allow us to compensate for uncertainties in our measurements.

- Computing: After entangling several “qubits” (circuits that store quantum information), operations on one qubit affect all the others, which could significantly decrease the amount of work we need to do per computation.

Single-Photon Interference

This effect is a bit easier to explain than entanglement, but it is just as weird.

You may have heard that photons act as both particles and waves. Wave-particle duality doesn’t matter much for the amounts of light that humans typically interact with, but it has some bizarre implications when we go down to single photons.

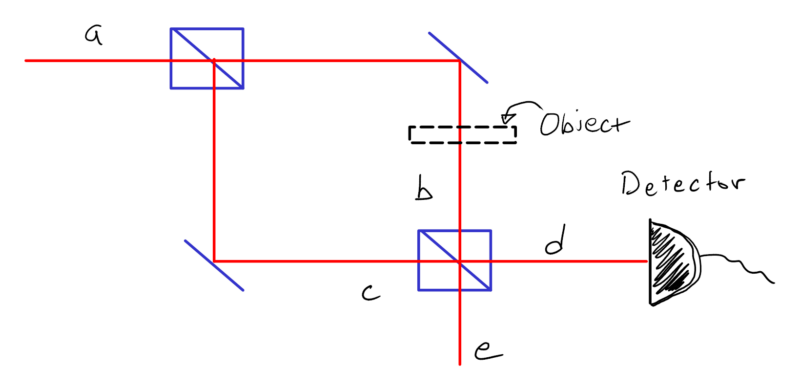

Consider the following optical setup:

Photons enter the system at (a), go through a 50/50 beamsplitter, bounce off a mirror, go through another 50/50 beamsplitter, and exit at (d) or (e) into detectors.

You can think of 50/50 beamsplitters assigning incident photons randomly to one of two outputs. So if we treat the single photon as a particle, we’d expect the photon to exit at (d) or (e) equally as often.

But if we treat the single photon as a wave instead (and assume that the two possible paths through the system are equally long), the photon will always exit at (d). The wave interferes with itself at (e) and cancels itself out.

It turns out that the wave-like behavior is what happens in real life! If we send a stream of single photons through this system, then every single one will exit at (d), which we can measure.

This result was hard for me to accept because it just… doesn’t happen at macroscopic scales. Imagine if a restaurant has two main-course options (beef or chicken) and two dessert options (cake or pie), and every single person somehow chooses either {beef and cake} or {chicken and pie} and no other combination. It would be completely improbable, yet this is exactly what happens on the quantum scale.

Single-photon interference isn’t just a fun little quirk of physics; it also has many real-world applications that we constructed in the lab:

- Interaction-free measurement: Suppose we have some object in the way at (b), which prevents interference at the second beamsplitter. Normally, we would need a photon to hit the object to detect its presence. But in this setup, a photon could take the path (a)→(c)→(e), allowing us to detect the object without the photon hitting it! This effect is theoretically useful for taking microscope images of light-sensitive materials, although we don’t yet have any practical microscopes that use this effect.

- Interferometry: When the two paths through the system are not equally long, the probability of photons exiting at (e) varies with the path length difference. This varying probability allows us to measure minuscule changes in distance! Interferometry is used all across science and engineering, particularly in fields like nanofabrication that require extraordinary measurement precision.

Two-Photon Interference

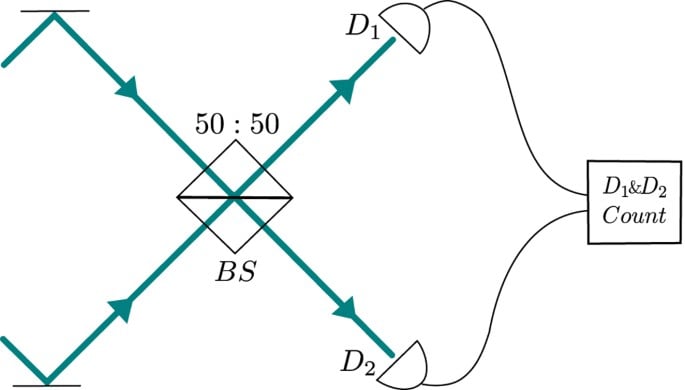

Two-photon interference is like single-photon interference but with – you guessed it – two photons! Instead of sending a single photon through two beamsplitters, this time we send two photons through a single beamsplitter.

I pulled this image from some Nature article.

In general (if the two photons are not identical or enter the beamsplitter at different times), nothing exciting happens. Each photon interacts independently with the beamsplitter, and there’s a 50/50 chance of whether they both exit through the same path.

But when the two photons are identical and enter the beamsplitter at exactly the same time, something truly astounding happens – they always exit through the same path. In other words, they become entangled in space!

Like single-photon interference, two-photon interference happens because photons are waves. Similarly, you can use the restaurant analogy to see why I thought this effect was so ridiculous until I actually observed it in the lab.

The main application of this effect (as far as I know) is to make better interferometers by exploiting the photons’ entanglement to make more precise distance measurements. LIGO used a similar technique to detect gravitational waves back in 2015.

Photon Antibunching

This effect is, in my opinion, the strangest one because I still don’t quite understand it.

The gist is:

- We have a photon source (laser) that we know generates pairs of single photons.

- We use one detector aimed at one of the photon outputs to measure a quantity \(g^{(2)}(0)\) (second-order coherence).

- We expect to get \(g^{(2)}(0) = 0\) because that’s how a single-photon source should behave.

- We get \(g^{(2)}(0) = 1\). Sad.

- We turn on a second detector aimed at the second photon output.

- We magically get \(g^{(2)}(0) = 0\), even though we changed nothing about the source.

Ok, so what does any of this have to do with birds? Not much, to be honest, but I just wanted an excuse to talk about pigeons.

Look at these puffy pigeons I saw a few weeks ago!

Pigeons are amazing creatures and have many talents (like drinking through suction, which surprisingly few other animals can do), but one of their most remarkable skills is navigation. Despite not having access to GPS technology, pigeons almost never get lost when flying home, even when home is hundreds of miles away. This skill is one of the reasons why pigeons are everywhere today – humans have used domesticated pigeons to communicate reliably over long distances as far back as ancient Egypt.

So how do they do it? The short answer is we still don’t quite know for certain. There are plenty of exotic theories out there, ranging from “pigeons can hear magnetic fields” to “pigeons can smell the way home”. Although these theories may well be true and contribute to pigeon navigation, the coolest and most compelling theory (in my opinion) is that pigeons can see magnetic fields, thanks to some special proteins in their eyes called “cryptochromes”.

Recent evidence suggests that cryptochromes work because of quantum entanglement and another exotic theory called the “quantum Zeno effect”02 The quantum Zeno effect basically says that if you measure something frequently enough, it never changes. It sounds ridiculous (because looking at something is technically a measurement), but somehow it is correct. . When blue light hits a cryptochrome, it causes two electrons in the protein to become entangled. The interaction between these electrons and magnetic fields then affects how quickly the protein reacts with other chemicals in the eyes, translating into an optical signal in the brain.

Interestingly, cryptochromes are not specific to pigeons – all birds have them. However, we have also found that cryptochromes in pigeon eyes are much more sensitive to magnetic fields than those in chicken eyes (because chickens rely less on long-distance navigation). This evidence further supports the theory that cryptochromes (and by extension quantum entanglement) is mainly responsible for pigeons’ amazing navigational abilities.

All this to say that pigeons (and I suppose all birds) are quantum magnetic wonders, and we should all appreciate them more.

- It reminds me a lot of the Rube-Goldberge-esque games I enjoyed playing as a child! Something about placing things into grids is just so oddly satisfying to me. back to text ↑

- The quantum Zeno effect basically says that if you measure something frequently enough, it never changes. It sounds ridiculous (because looking at something is technically a measurement), but somehow it is correct. back to text ↑