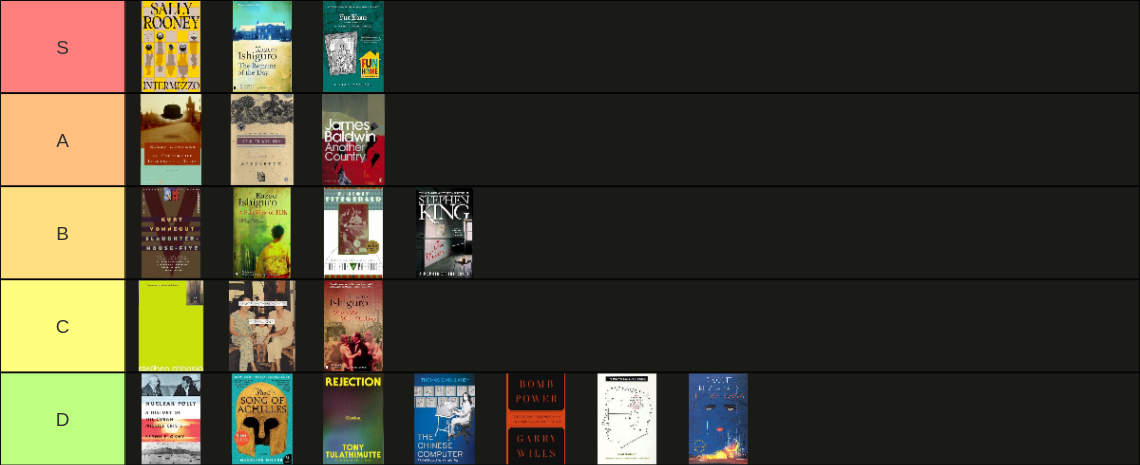

books I read in 2024, ranked by Kai V. '25

and thoughts on the best ones

This year I read 20 books. Here they are in a tier list, ranked based on personal enjoyment/emotional impact and not at all on literary merit or perceived quality, because:

1) I don’t trust myself to make a competent assessment along that axis—eg Ocean Vuong’s poetry collection would probably be higher if I felt capable of Actually Understanding Poetry, but I want to avoid arbitrarily ranking critically acclaimed books higher based on some aspect I don’t feel like I understood.

2) I think you only care about the enjoyment/impact axis if you’re reading this, like you can just scroll a Harvard Great Books class syllabus or something if you want a books-by-literary-merit list.

Here’s how you should interpret the letters, and a list of all the books.

- S: will reread again and again

- The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

- Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

- Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

- A: really great, would recommend to ~anyone

- The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

- Another Country by James Baldwin

- B: solid, would strongly recommend to a friend

- Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

- A Pale View of Hills by Kazuo Ishiguro

- This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- On Writing by Stephen King

- C: fine lol. thought provoking I guess.

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

- Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

- When We Were Orphans by Kazuo Ishiguro

- D: mildly positive reading experience. probably will never touch again

- Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis by Serhii Plokhy

- The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

- Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte

- The Chinese Computer by Thomas Mullaney

- Bomb Power by Garry Wills

- The Man Who Loved Only Numbers by Paul Hoffman

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Originally I was going to write something about every single book on the list but now I realize that I am lazy. However, I feel really strongly about my S tier books so I’ll say something about each of them.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro

This is my favorite book I have ever read—for its emotional impact on me, but also for expanding what I thought you could do with literature. I’m in love with the way Ishiguro approaches characterization through unreliable narration. I often hear “unreliable narrator” used to refer to an agent with ulterior motives who purposely obscures information from the reader. But that’s not how I’m using the term—instead Ishiguro evokes an unsettling feeling that something is wrong, that the narrator’s own model of their world is precarious, even if the narrator seems largely sane and competent. The details the narrator relays tell you how history shaped them. The details the narrator doesn’t relay tell you about their psyche, the nature of their denial, the gaping hole that the reader is forced to reckon with and fill in on their own.

Even in Ishiguro novels that I’m less fond of (Klara and the Sun was mid; When We Were Orphans was mildly incoherent), this characterization is always skillfully done. But nowhere is it done better than The Remains of the Day. A butler past the prime of his career takes a tour through England and reminisces on his days serving his former lord. There are maybe two sentences in the novel in which he directly addresses the feeling that we might expect from someone in his circumstances. Everything else has to be inferred. Yet the subtle pressures the story applies to us shape the inferred conclusion so sharply and clearly that the result is far more heartbreaking than any explicit admission of emotion could be.

It seems like Ishiguro doesn’t hit hard for everyone, but I’d still say this novel is my highest recommendation.

Fun Home by Alison Bechdel

I read the first chapter of Fun Home at the start of my junior year of high school. It was part of an anthology assigned in English class. That single chapter left such a deep impression on me that, five years later, when I happened to pick up this book from a store shelf and leaf through it, I recognized it immediately—despite having long forgotten the author and title—based on what I can only describe as the rhythm of the writing, and finished it standing right there at the shelf for two hours.

Fun Home is a graphic novel about Bechdel’s childhood, focusing in particular on her tenuous relationship with her closeted father and her own realization that she was gay. Most of my sense of literary aesthetic (as in, my sense of whether a piece of writing is beautiful or not) is derived from that first chapter, which accomplished its task so completely and perfectly that it convinced me forever of the power of a well-crafted personal essay. It’s not an exaggeration to say that if I hadn’t read that, I likely wouldn’t be writing blogs now. I don’t know if I just reread it that many times when I encountered it in high school, or if it struck a deep, already-existing chord, calling to the surface a sense of pacing and beauty—on the sentence level and on the essay level—that already existed inside me.

Its graphic novel nature enables each page to tell multiple sub-stories at once as parallel threads which sometimes intersect. There’s current-Alison’s train of thought, in full sentences. Past-Alison’s perception of the story, in dialogue and illustration, which also work to frame current-Alison’s thoughts, and all the parallels between her and her father, set up as camera angles and matching silhouettes. It’s really impressive if you read the actual book. Bechdel generally achieves a smooth, cohesive stream of thought from the beginning to the end of a chapter, in which three or four threads are set up when the chapter begins and interact through dialogue, illustration, literary allusion, and caption until the end. It’s done very precisely and elegantly.

Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

This was by far my most surprising read of the year! I’ve tried Rooney before but have always found that I cannot stand her writing. Normal People is one of the few books in the world that frustrated me so much that I just stopped reading it. (I think it’s the only book I’ve ever given one star on Goodreads lol.) After Intermezzo, I’ll probably give her other novels a more serious chance again.

Here were my two problems with Normal People:

1) I find it really frustrating when the central conflict of a story could easily be resolved by clear communication, especially when we’re meant to believe that the characters are Deep, Thoughtful, Kind People. I’m told this is just how things turn out sometimes in real life, but it doesn’t make for an engaging story. Maybe I’ll relate to this kind of thing one day when I’m inexplicably in love with someone I don’t know how to talk to?? What??

2) Rooney’s writing style is usually quite dry? She describes the chain of events as it’s happening, using the exact same tone across all situations. She omits quotation marks as a stylistic choice, merging the character’s experience of reality with their own stream of consciousness. I mean, I get it. I also hate it.

These two aspects of her writing unfortunately totally prevented me from appreciating the deep understanding of human relationships that each rave NYT review claimed her novels captured. Happily, neither was a problem for me in Intermezzo.

Intermezzo follows two brothers, a decade apart in age, navigating their very different spheres of life after the death of their father. Because the story is written by Sally Rooney this entails some complicated romantic entanglements. I felt that the conflicts here were true and that the characters tried their best to communicate with each other honestly—and when a misunderstanding occurred it was for a real, substantive reason (which—yes—can be human weakness: fear, cowardice, pride), as opposed to feeling contrived for the sake of having a conflict.

The writing style might have been my favorite aspect of the novel. The novel hops between the perspectives of Ivan, the younger brother; Peter, the older brother; and Margaret, one of the women involved. Rooney employs a distinct tone for each of them which feels pretty far from her impersonal dry style in previous stories, and because it feels so much like we’re actually listening to the thoughts of the characters, the omission of quotation marks works to merge the current character’s experience of reality into their stream of consciousness. (This is maybe the first book I’ve said this about?)

I think, also, that characterization can easily feel stilted or awkward. An author tries to shove too much into one character. Different bits don’t make sense together. Or, in fear of this, the author shrinks back from too much explicit characterization altogether. Intermezzo does a good job of striking a difficult balance here: Peter and Ivan felt very true.

Looking back rationally on the story, I think Peter’s ending was a little bit contrived, and I loved Margaret’s chapters but think the book would have been more cohesive without her external perspective, with more space to develop the brothers. At its core it’s about the relationship between Peter and Ivan, and I get that Margaret was supposed to deliver some reasoned external perspective, but I wish there was a version where we only perceive the brothers through each other’s eyes.