by the time you notice it’s too late by Vincent H. '23

anime, bloons, and piano

i. i watched the anime attack on titan last year and liked it a lot. there’s one short scene i want to talk about in this post; it is probably my favorite 30 seconds of the entire show (minimal spoilers present and no context required):

in this scene, one of the antagonists appears and transforms into a titan. the commander of the protagonists sees this and shouts “keep on the lookout! locate his allies!” as he knows the other antagonists must be nearby. however, before he can even finish his command, the rest of the enemy titans materialize behind him, and then the commander turns around and realizes he is probably screwed. in other words, by the time he knows to look for the other antagonists, they have already arrived

ii. this reminds me of a game i played as a kid, the bloons tower defense series

the game works as follows: each round, some bloons (balloons) appear on the screen and your job is to pop as many of them as possible. you pop bloons by placing towers with abilities like freezing bloons or throwing darts. you have some fixed number of lives (say, 200) and each bloon you’re not able to pop results in the loss of 1 life

many of my classmates played bloons tower defense every day during my elementary school recess. while watching them play, i noticed a pattern that i was not able to explain at the time: although each player started with 200 lives, if there was ever a round where they lost a few lives then they would usually lose the entire game within the next 1-5 rounds

now that i’m older i think i understand why this happened. for the most part, each round in bloons tower defense is harder than the previous one by a nontrivial margin. this means that if your towers aren’t capable of popping all the bloons in one round, they’ll probably do even worse on subsequent rounds, so unless you’re experienced or have been saving up money for a major purchase you’re likely to quickly reach a round where your towers are completely outmatched and you lose all your lives

iii. the common thread in these examples is this: by the time you notice a problem, it is often too late to begin acting to address the problem. this is because the problem’s effects might be a very late signal for the problem’s emergence. in many cases it is such a late signal that it is barely actionable. but enough about anime and flash games; let me give some more legitimate examples:

i played piano briefly in elementary school. i was never good, but at some point i got to the state where i could sit in front of the piano, know where all the keys were relative to my body, and, say, play the E5 key with my right index finger without looking at the keyboard. this is a wonderful state to be in because it means you can read sheet music and know where to put your hands without ever having to take your eyes off the music whereas, if you didn’t know where all the keys were, you’d have to alternate between looking at the music and the keys

anyway, in fifth grade i quit piano and began practicing very infrequently. i went a few days at a time without practicing, and each time i returned i was still able to remember where all the piano keys were, so i thought i was doing fine. then there was a time where i went a few weeks without touching a piano, and when i came back i could tell where most of the piano keys were but would occasionally mess up, say, 10% of the time. no worries, i thought, that means i’m 90% as good at piano as i used to be, and i can get back to 100% with a bit of practice

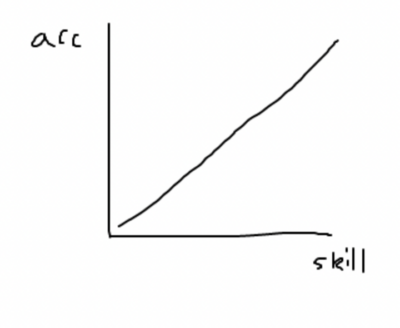

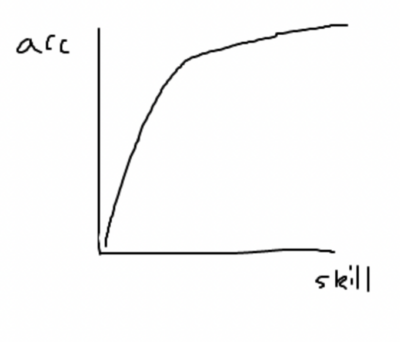

it turns out a bit of practice wasn’t enough to get me back to 100%; in fact, ever since fifth grade i have never again been able to reliably tell where the keys on a piano are. the problem was that, in using key accuracy as a proxy for piano skill, i’d accidentally equated the two. fifth-grade-me had implicitly assumed the graph of key accuracy vs piano skill looked something like this:

when in reality it was something much closer to this:

these two graphs are a world apart; in the first one, if your accuracy slips from 100% to 90% you’ve only lost 10% of your ability, while in the second one, by the time your accuracy slips from 100% to 90% you’ve already lost almost all of your ability. the latter is essentially what happened to me with piano; i didn’t have good metrics in place for gauging my piano ability, and as a result, by the time i noticed my decline i could not easily reverse it

iv. i think many forms of procrastination fit this pattern as well. for example, consider this point from one of my favorite blog posts about college:

“At the end of college you should probably have a good idea about what to do next. Here’s the default way to figure that plan out: (1) don’t think about it for three years; (2) get really stressed during your senior year because you have no idea what you want to do; (3) notice that all your friends are interviewing for jobs in consulting, finance, and MicroFaceGoogAzon; (4) accept a job from consulting, finance, or MicroFaceGoogAzon.”

it feels obvious to me that, if you’re trying to make a difficult decision, the realization that you have no time left is a ridiculously late signal for beginning preparations to make the decision. unfortunately, the author of the blog post was right in that this behavior is common among undergrads, i guess because earnestly confronting the question of what to do after college is scary or something

v. all this illustrates one common solution to the paradigm of not noticing problems until it’s too late to solve them: just notice the problems earlier. notice which bloons your towers struggle against even during the rounds where you don’t lose lives. notice how your fingers can’t make the same motions they used to be able to well before you start missing keys entirely. notice the passage of time every year, every month, every moment of your college experience, not just when you become a senior

the other common solution to this paradigm is to plan ahead of time for how you’ll address an issue once you notice it. in other words: you can notice earlier so you have more time to come up with a solution, or you can come up with a solution in advance so that it doesn’t matter if you notice late

vi. freshman fall was easily the worst semester of college for me. it was my lightest semester in terms of courseload, and everything was on pass/fail, but it was also the only semester where i felt truly overwhelmed. i joined many clubs and applied for a biotech urop, and then halfway through the semester classes and social obligations began taking up all my time and i had zero bandwidth for working on research or exploring mit or meeting new people

it turns out having no free time is another problem that people tend to not notice they have until it’s too late to address well. you notice late because, after taking on new commitments, the full impact of those commitments on your schedule usually isn’t felt until some weeks or months later. at that point it is too late to address the problem effectively because, once you have no free time, it is difficult to find time to think clearly and decide on a good course of action

my life last semester was objectively busier than it was freshman fall, but i never reached zero bandwidth because i’d learned both to notice earlier and to come up with solutions ahead of time. i’d learned to always pay attention to how i felt about the present and the upcoming future, i’d learned to keep an up-to-date ranking of the order in which i’d drop each of my commitments if i had to, and most importantly i’d learned that having no free time was a problem i had to actively combat rather than a problem i could simply avoid without doing anything about it

vii. people often say that you shouldn’t think too hard about your future problems because, regardless of what happens, everything will probably turn out okay in the end. if it wasn’t clear from the rest of this post, i think this sentiment is extremely misleading

do i believe you should obsess over the future in a way that worsens your state of mind or comes at the cost of living in the present? of course not. but while the future-focused mind is prone to anxiety, i think many of us, myself included, have overcorrected and begun using the possibility of anxiety as an excuse to justify procrastination and nearsightedness. it’s true that things will probably turn out okay in the end regardless of what you do, but it’s also true that there are many different pathways through which things can turn out okay in the end, and you prefer some of those pathways to others. sometimes i feel like i have forgotten this

viii. i spent the first eighteen years of my life thinking that i could solve all my problems through good fortune and individual brilliance, probably as a result of doing too many math contests. then i became aware of more complex problems like community-building and mental health and startup management. through those encounters one thing has become abundantly clear to me: hard problems do not solve themselves; they are solved by good systems