leaning in by Paolo A. '21

on choosing lives

I am starting this post on Thursday, April 8, 2021, and today, it could be a little bit warmer. I’ve been sitting outside the Stud for about half an hour, eating my lunch, and the wind is getting to me. I could choose to get up and move to a different bench 20 feet away, one that is in the sun rather than the shade. But then I wouldn’t be able to type as easily because of the glare. And that’s why I’m out here, primarily: to write. It’s been a while since I’ve done that, in part because I’ve been struggling with a big decision. Writing itself, of course, is a structured way of organizing my thoughts about the big issues that I’m worried about, which is a big reason that I’m writing this post.

In one week, I need to decide what I want to do with my life.

OK, perhaps a bit too dramatic of an opening line. Life is not one decision that you can never come back from. I can always make new choices down the line if I figure out that my choice wasn’t right for me. In the 5 minutes since I started writing this post, I decided I was too cold, my hands started to feel a bit slow, and I’ve moved into the sun. But at the same time, the decision that I have coming up in one week — whether to go to graduate school, or whether to accept my job offer at the finance company I worked at last summer — is very, very big, and will impact the trajectory of my life.

For many of you readers who are high school seniors, this all may strike a chord with you as you face a very big decision: where to go to college. Choosing between colleges was the biggest decision of my life when I was in your shoes four years ago. I’ve been meaning to write a post about choosing between colleges, choosing between lives, ever since I became a blogger — I have notes from last September, filled with content about difficult decisions. But I didn’t expect that when it came time to write that blog, I would be so conflicted about my own decisions, too.

(In some ways, this post is the spiritual successor to . Obviously, you don’t need to read it first, but it might help you to understand where I’m coming from as I think about this all.)

This post has two purposes: one, a record of the hundreds of thoughts and conversations I’ve had about my own decisions. But two, I hope that this post has some advice (implicit and explicit) if you’re trying to make choices about your future: whether college, major, career, or anything else.

First, though, I want to explicitly recognize why these decisions are difficult. No one will ever say that these decisions are easy, but I think it’s important to verbalize a few reasons that make it so hard.

-

Incomparable features: There are for college decisions, things like financial aid, graduation rates, community, dorm systems, quality of your department, curricula, access to research, opportunities afterward, location, weather, “fit”, and so on. For me, facets like work-life balance, novelty within my work, career progression, ease of returning, freedom, pay, … Even if you can figure out how to rank within each feature (which is better: a bigger department with more resources, or a smaller department that lets you get to know faculty more?), trying to compare across these groups can feel impossible. What is worth more: $1000 in financial aid or core curriculum that you enjoy more? Or comparing more sunny days to how well you fit with the people? It’s not even an apples to oranges comparison, it’s like trying to compare apples and office supplies. There is no intrinsic basis for comparison.

-

Uncertainty: The decisions that we are making are about the future, and there is inherent uncertainty as to how the future will play out. No matter how much research you do about colleges, things might change in ways you never could have expected. Maybe you think you’ll be a computer science major now, but you might find that you actually love nuclear engineering. Or maybe you won’t enjoy constant sunny days as much as you thought you would, and you actually do like having seasons and winter. If I choose to go to graduate school, I have no idea if I’ll come up with good research ideas, let alone if that research will succeed. If I choose to go work in finance, I don’t know exactly how well I’ll like the work I do, what projects I’ll get placed on, etc.

-

Optionality: Humans tend to value the act of having choices, a fact that has been shown in behavioral economics experiments01 now, sometimes behavioral econ likes to call this kind of behavior “irrational”. i don’t like that term, because it has connotations that we shouldn’t be doing it — “just be more rational”. but it is </span><span class="md-pair-s "><em><span class="md-plain">human</span></em></span><span class="md-plain"> for us to value these kinds of things, and it is better for us to be aware of them, rather than not. (). People are willing to pay just to have choices and options, even if they aren’t valuable. But the act of deciding, particularly for decisions like colleges and jobs, means that inevitably, some doors will close. Once you choose a college, it’s impossible to completely restart and explore the other college — while transfer applications exist, will you be a different person for having spent a year at another institution. If I decide to work now, the door to a Ph.D. closes somewhat (including the offer that I have in front of me right now). Not entirely, but it does get harder to go to grad school. If I decide to go to grad school now, I lose the job offer I have open, and there are no guarantees about if I’d be able to get it back.

-

The choice between different options, not better/worse options: Even if you get past all of the above, there’s one, final hurdle to decision-making: the fact that the decision you make will lead to different lives. You are choosing between what kinds of values you want to have in the future, between different people that you want to become. Both paths may be equally good, and you just have to choose one or the other, and that is … hard. (This is the message of , a wonderful blog about choices that I encourage reading.)

And so if you are stuck, deer-in-headlights, not sure how you’ll choose: wow, I feel you.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the past few weeks chatting with people about their paths. Today’s is with a grad student at MIT: we talk about his journey into economics, whether he enjoys graduate school, if he wants to stay in academia or work in industry, if he has any regrets. I’ve had dozens of similar conversations with other graduate students and professors who have chosen that life. But I’m also talking with people who have made the opposite decision: undergrads that have decided to work first, people working at the company I’m considering. And I’ve also talked to the people who tried out both: people who have gone to grad school, but now work in industry, or people who started working in finance, and have thought hard about going back to graduate school.

many, many thoughts

I like having these kinds of conversations with people, talking about the decisions that they’ve made and how it’s turned out for them. It helps me understand who people are, learn about paths I didn’t know existed. How they made their decisions. The values that they considered, the factors that led them towards one path and away from another. And perhaps most importantly, what kind of person I want to be

Talking to other people about their choices has a problem, though: the choices were theirs. Making a decision, particularly about where you want to go in life, and what kind of person you want to be, is inherently an individual decision. No one can tell me what kind of person I want to become. Those are answers that can only be determined through understanding yourself. No matter what, I am the person that has agency over the trajectory of my own life.

I am acutely aware of the above two paragraphs as I write this post, a post simultaneously about my own choices and with advice for others making their own decisions. I don’t want to just tell you what decision to make — my goal in writing this post is not to tell you to choose MIT, but rather to help you to make the best decision for you. But how can I, without even knowing you, tell you frameworks that you should use to make your choices? What chance is there that the words that I write will actually help?

I don’t know. But here I am, writing this post anyways.

Perhaps it’s time for me to talk directly about my own decision. I’ve been writing around it for the duration of this post, and I think it’d probably be worthwhile to talk about it in detail.

One option I have is grad school. A week after my , I was incredibly, incredibly fortunate to receive a fellowship that makes graduate school in economics possible, and is a very useful bargaining chip for getting off of waitlists. And so that path is now open for me to walk down — a path that, in 5 or 6 years, assuming all goes well, will lead to a Ph.D. in economics.

Grad school seems really, really nice for a few reasons. It’s a chance for me to study topics I care deeply about: education, social connections, networks of people, and more. I get to keep using tools and methods and knowledge that I’ve learned throughout undergrad. I’ll be challenged to create my own original research. I’d reach the forefront of knowledge in my field, and hopefully, push that knowledge further. I’d become peers with the inspiring people I’ve learned from and about in my economics classes.

On the other hand, graduate school is scary for many reasons. Perhaps the biggest one is the fear that it’s not what I actually want. In graduate school, your entire work is centered around trying to make good research, and I still don’t know if I’m up for that. Beyond that, graduate students, particularly in economics, have pretty bad rates of mental health issues, especially because it’s easy to tie one’s self-worth to your work. Do I think that I can handle that? And if I can’t, and I decide to leave my program early, I’d end up basically back where I am now, unsure of where to take the next steps (but also hopefully with more skills and more knowledge about what I want to do in life).

The other option that I have available is a job in finance. I’d be at the company I interned at last summer, working to systematize logic about markets to help portfolios to grow. For me, working here feels like a place to spend a few years to try and grow as a person: the company’s culture is focused on helping people understand their weaknesses and growing from that. I also really enjoyed being around these poeple last summer; they thought about interesting questions beyond just work, and I could very easily imagine myself enjoying the spontaneous chats with them.

However, I don’t actually care that much about finance. Within economics, I am much more interested in the personal, everyday actions that people take, rather than trying to understand economies at scale — i.e., exactly the kind of work I’d be doing at this company. And of course, this isn’t even getting into the moral implications of working in finance for a few years (or longer). In my , we read an incredibly interesting article about Wall Street traders and their moral economies — the ways in which their morals and values influence their actions within an economy, and the ways that economic factors in turn influence morals and values. This company was the first time I found people in finance that actively engaged in discourse about whether their work was moral or not, and what they were doing as a result of it. I found people who deeply felt that the best thing they could do for the world was to earn as much money as possible, and then donate large, large amounts of it.

I worry about what kind of person I’d become in finance. Am I okay with that?02 to be clear, grad school and academia are not free of this problem either. the “ivory tower” of academia can feel very, very far from actually having impacts on people’s lives. and so that’s yet another thing to consider. Do I think that I could be the kind of person that I want to be? Do I think that I’d feel happy in such an environment? I also don’t quite know what the future would be like for me in this career. Would I stay at this company for a long time? Would I get bored after a few years — and if so, what could I possibly move on to?

To be clear, I am incredibly lucky and grateful to have both of these options available to me. I could imagine myself being happy in either one. They’re both great options, but for very, very different reasons. At the same time, they each have their own drawbacks. There is no safe option that I can take; each path I could walk down has its own potential pitfalls, and that scares me and my risk-aversion. Each path also takes me , and those decisions cannot ever be fully reversed.

On Saturday, the weather is perfect. I take a blanket and book outside and set aside a few hours to think about the decision I have in front of me. It’s one of those days with a bright blue sky and clouds that float past, always changing in shape. Transient.

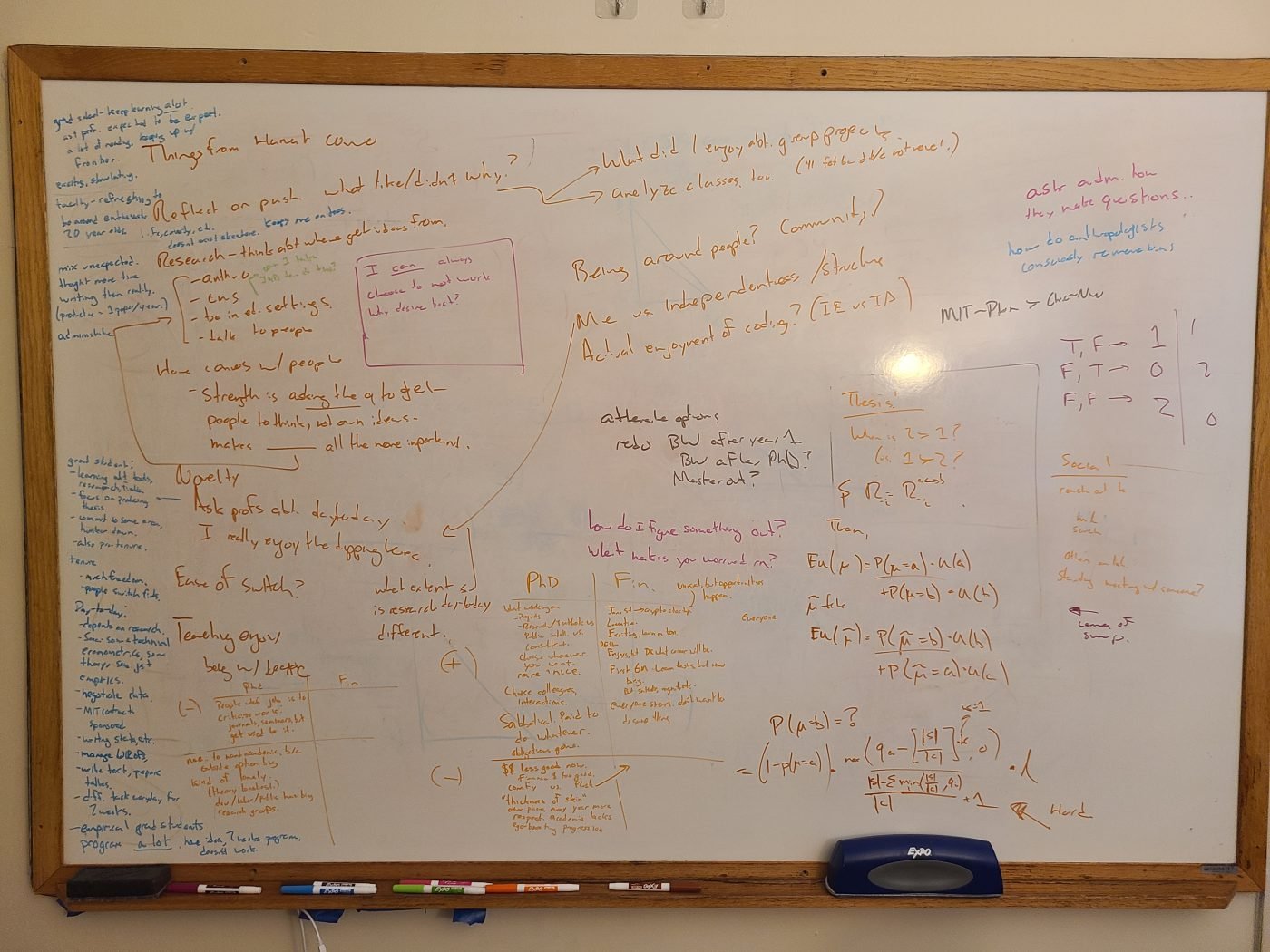

About a year ago, there was a when someone pointed out that some people have inner monologues, while some people don’t. I fall into the latter camp. When I think about something, my brain is filled with vague, amorphous thoughts, that only become coherent when I attempt to verbalize them or put them down in writing.03 this is another reason i like having conversations with people, because the act of explaining something to someone else just helps me understand more where the gaps in my knowledge are. writing sort of fills this gap (i took it up in quarantine, when my socialness went down by a lot), but it’s not quite the same. The fact that we often draw inner thoughts as clouds, hovering above someone’s head, is not lost on me.

Partially as a result of this, I like thinking about frameworks: conscious ways to organize thoughts, things like or . During grad school visit days, a Ph.D. candidate recommended that I take a peek at , written by two people who teach about design at Stanford, and have created a class where students apply design principles towards crafting a life. Chapter 2 of this book is called “Building a Compass”, identifying the values important in your work and values important for your life, and that those values can guide you through big decisions.

Of course, identifying these values is incredibly difficult: Designing Your Life says that you should spend at most 30 minutes writing down your philosophy (what’s important, what you value) of work, and 30 minutes for your philosophy of life. For me, the process of knowing that has taken years. These are, after all, the existential questions about life — what do you want out of it? What matters to you?

Even now, spending hundreds of hours thinking about this over the course of my senior year, I’m still not sure about exactly what these values are. I’ve stumbled onto a few ideas, like:

-

Being around good people that will help me grow

-

Having work that is interesting, challenging, and feels not-repetitive / not-gruntwork

-

Being interested in the topic area of my work

-

Feeling like I can do good through my work

In some ways, these values are informed by what I didn’t like about work that I did throughout MIT, rather than things that I did. I didn’t really like my internship at [redacted] because I was doing work that felt very similar to things I had done before; I care about being around good people because at [redacted] I felt like I didn’t really connect with anyone there and it made me sad.

I consciously organized my summers and IAPs to try out a wide variety of possible career paths for me: consulting, finance, academic research, the public sector. On paper, I’m supposedly a person who has checked all of the boxes to know what I want out of life. Yet I still can’t help but feel like I don’t have enough information to make a well-informed decision. My internships were just a few months long. In UROPs, and you only do what someone tells you to do; in grad school, you might spend years creating a single piece of research. How am I supposed to make such a big decision when I don’t know exactly what I like?

But that is the nature of life, I suppose. Every day, we are asked to make decisions, and we cannot possibly know the results of all of them in advance. We are simply told to choose, and to accept that some future will come.

At this point, I think that I’ve thought about my two choices enough that there are two big questions that I want to answer before I decide.

-

Do I think that I would do alright and be happy in grad school? I really like the idea of grad school, being able to work on the things that I want to work on. But am I confident enough in my abilities to do research, make good ideas, to enjoy the day-to-day grind of working with data and crafting papers, to make it through? My expectation for myself shouldn’t be to be the best person in the world at research. By definition, I should expect myself to be the median researcher in my cohort. But do I think that I can do it, and moreover, enjoy it?

-

Would I be happy working in finance? Right now, I think I have a decent-enough sense of the things that I care about. I care about the communities of people who are around me, and understanding how culture and community matter. I care about education, once called “”, and thinking about how to make education as a whole as impactful as it was for me. But in finance, I wouldn’t be able to work on any of that. While I would be around good people — I loved the kinds of people I was around this past summer — it’d be people who, by nature, thought less about these things. The saying goes that you are the average of the five people you interact with most, and that will change no matter what option I choose. But do I think that I will be able to find the people that I want to be like in finance? Could I be the person that I want to be?

Again — both are risks. There is no safe option. I must lean into my discomfort, one way or another.

As a small interlude, I’d like to recount my own process of deciding between colleges. I checked my calendar, and I committed to MIT almost exactly four years ago. Crazy how time flies.

To be clear, this post is not meant to convince you to go to MIT. I can’t tell you what to choose, what things to consider, because I don’t know who you are and what things you care about. This post is just to share my own path, my own reasoning. Maybe it’ll connect with you, and maybe it won’t. But you are person who is in control of your life, not me, not anyone else that has given you advice. In the end, it is your choice, and your life.

My choice was between University A and MIT. During my visit day at University A, I found people who were just so happy to be there, people who genuinely seemed to be enjoying their lives in college. I could go there, spend as much time on school as I wanted to (either choosing to not focus on academics, or putting in enough effort to double or triple major, if I wanted). And I was lucky enough to get a big merit scholarship there, too.

MIT, on the other hand. I started falling in love with MIT after being admitted. Beyond just the academics and opportunities and everything, I loved the people I interacted with, the upperclassmen I talked to. People who were passionate about whatever they were doing, no matter what. At the same time, I was scared about comMITting because of the challenge and how hard MIT could be. I remember very strongly one night at CPW, sitting on the roof of the frat I was hosted in, thinking how my decision would end up impacting my life. Staring at the Charles and wondering how my choices would carry me on to some unknown future. And how MIT would be a risk for myself.

In the end, I chose the place that I connected with people more at, the place with people that I wanted to get to know for four years. I also realized that I wasn’t choosing MIT despite the risk; in some ways, I chose MIT because of the risk, because I wanted to be a person who embraced the uncertainty and the challenge.

The phrase “leaning in” comes from a piece of writing by my good friend Avery N. ‘22 that I read last September, when I first began drafting this post. In the grand scheme of their piece, it wasn’t a very important line. But in that moment I read it, it reminded about all of the feelings that I had when choosing MIT. How sometimes, you can’t know how things will turn out, but you must lean into the discomfort anyways.

If you’re reading this post, trying to choose where to go to college: think about the people that you meet. That could be you, in a couple of years. Which people do you want to be around? Which kinds of people do you want to be?

You are valid for whatever you decide to choose. Just make sure that when you make your decision, you’re making it for your reasons, and not anyone else’s.

On Sunday, there’s a meetup in a park with some other Econ PhD admits. We sit around in small groups, joke about how it’s so much better than a Zoom hangout. I chat with someone about the act of choosing. He talks about how he’s already mentally committed to a school, and is coming from a job in finance that he really didn’t like. I learn that another person at the hangout interned at the same company that I did; he turned down his return offer. These people could be me, potentially. I could be the person who turned down my job in industry, decided that I wanted to spend time on research for 6 years. But is that me? I don’t know.

On Monday, I chat with a good friend of mine who’s faced his own difficult choices. After a very circuitous path, he’s working primarily in education, working to better math education and do good for the world. In another world, maybe I’m like him: turn down both offers, and spend my time teaching and designing curricula and working with education startups.

I mentioned above that I’ve had so many conversations with people about their own paths and perspectives. Throughout all of the questions and answers, I think there are a few things that have stuck out as useful advice for me in my own decision-making.

-

There is no such thing as a correct decision, because the notions of rightness and wrongness don’t apply to these kinds of big decisions. Once you’ve done the “easy” comparisons and cross off any choices you definitely like less, any option you have left will be good. Hopefully, this knowledge is something that removes stress; the fact that there is no bad option you can take means that any choice that you make will turn out alright enough in the end.

-

You’re making decisions based on the best information you have right now. There will, of course, be some amount of risk and uncertainty in any decision you make, and those issues sometimes just can’t be resolved. Trying to accept that you can’t know everything about how it’ll turn out is hard. But all will end up turning out OK.

-

You shouldn’t treat these choices (and your life) as something to maximize your utility over, because that’s not how it works. There is no single thing that will make you most happy. And pretending like there is will only make you more stressed, make you more worried than you need to be. You will be OK either way. There is no bad option.

-

Once you start going down a path, don’t keep thinking about what the other path might have been. When you commit, you should commit, and not worry too much about how you might have turned out the other way. Because if you do so, you won’t focus on the path that you did choose. Live in the present, in the universe that you did decide to choose. Don’t .

-

But if you find yourself unhappy, you can just re-evaluate your choice then, and change direction as needed. Even once you do choose, you aren’t beholden to that path forever. It’s always possible to change where you’re going: switching majors, transferring colleges, or finding a new job. And if you need to do that, all is well, because you will have learned something from the path that you have traveled on so far.

With respect to my two “big unresolved questions” earlier, this all means that:

-

Even if I’m not sure if I will enjoy graduate school, answering that question is impossible in the next few days. From what I know about myself, it’ll probably end up alright. And I have to accept the uncertainty.

-

If I go down the finance path, I should always make sure that I think about what kind of person I want to be, and whether I am becoming that person or becoming someone else.

In some ways, what makes this decision so hard is that it is a “values decision”. By that, I don’t just mean that I have to understand my values in order to make the decision. Rather, it is a decision that will fundamentally alter my values and the things that I care about. As a graduate student, I’d care much more about doing research well and about whatever topic areas I choose. In finance, I’d care about getting to the right answer quickly, spend more time thinking about the environment that I’m in, and I’d probably think differently about how I could do good for the world. It is a choice between two different futures. Neither good nor bad, neither right nor wrong. Just different.

On Tuesday, I chat with my girlfriend. I ask her if she thinks that I’m overthinking this all. She says yes — unsurprising, honestly. If you haven’t been able to tell from this post (or my past posts), I think myself into circles far too easily. She asks me a few questions.

-

Which do I think is more exciting? Both, for their own reasons.

-

Do I think I’ll succeed in each of them? Probably. And I can’t know more than that in these next few days.

-

Which is harder? Which is riskier? Grad school places a lot of pressure on you because it’s designed to make you a good researcher, and is risky because I don’t know how I’ll turn out. But that’s not to say that finance isn’t hard and risky, too; it’d just be a risk on the kind of person I would become, a risk on how much I’d enjoy work I didn’t connect with.

-

And finally: which person do I want to be?

These are not questions that anyone can answer for me, just like how I cannot answer them for you. You are the person in charge of your life, and no one can form thoughts for you. You are valid for choosing whatever path you go down; all that matters is that you feel like you are making your decision.

For me? I can easily see myself going down either of these paths. I can easily imagine a life where I become a grad student just as easily as I can imagine working next fall. They truly are two different futures that are equally plausible, and I only have the chance to choose one of them in this moment.

That night, I send an email to a manager and a recruiter at the finance company I worked at last summer.

Hi [redacted],

After much, much, thought, I’ve decided that I will not be accepting my offer to work at [redacted] next fall, and will instead be starting my PhD in economics at MIT next fall.04 !! i still am in shock about it not-infrequently. aaaAA

This choice was incredibly tough to make. I really, really liked working at [redacted], neither option felt “wrong” to me, and I can easily imagine another world in which I took the [redacted] offer instead and started going down that path.

[…]

It’s crazy to think that I started talking to you all way back in 2018; thank you both for everything over the past few years. [redacted] has helped me figure out a lot about myself, and I can’t thank you enough for helping me through it all.

Many, many thanks, and best wishes,

Paolo

In another universe, I’d be sending the same email to my professors here at MIT, and I’d be becoming a very different future self. But I can only live in one universe at a time. And that’s OK.

I am still scared of grad school, to be clear. But in this universe, I’ve decided to lean into that discomfort, and am excited to fling myself head-first into it all this fall. To start a new chapter in my life, and to hopefully become a person that I want to be.

To the 2025s: whatever you choose, make the most of it, and don’t look back. You will do great things wherever you go. When you commit, commit, and live your life to the fullest in the world that you have chosen for yourself. <3

- now, sometimes behavioral econ likes to call this kind of behavior “irrational”. i don’t like that term, because it has connotations that we shouldn’t be doing it — “just be more rational”. but it is human for us to value these kinds of things, and it is better for us to be aware of them, rather than not. back to text ↑

- to be clear, grad school and academia are not free of this problem either. the “ivory tower” of academia can feel very, very far from actually having impacts on people’s lives. and so that’s yet another thing to consider. back to text ↑

- this is another reason i like having conversations with people, because the act of explaining something to someone else just helps me understand more where the gaps in my knowledge are. writing sort of fills this gap (i took it up in quarantine, when my socialness went down by a lot), but it’s not quite the same. back to text ↑

- !! i still am in shock about it not-infrequently. aaaAA back to text ↑