SCIENCE! by Anna H. '14

I'm bad at it, sometimes

Signs that I would someday Do Science can be traced to when I was 6 +/- 1 years old and decided to make a space-themed board game. Here’s a sample tile that my sister and I have since rediscovered.

I’ve also rediscovered a diary that I kept in first grade. My favorite entry reads (unfortunately I don’t have a picture):

“One day I went to Nasa! It was fun, very fun! I went on a ride that looks like this*. then when I got home I con’t think of anithing But Nasa! So I Dicided to mak a book about Dinosaurs! So I set to work.”

*Accompanied by a drawing of what I assume was meant to be a spaceship.

Apparently I was a little confused about what NASA was, or did. I don’t think I ever actually went to NASA; maybe I went to a science museum and saw some NASA signs in the space section and figured that that’s what the whole building was. The point is: I thought space was cool.

High School science was a less successful experience. In 9th grade, we looked at fruit flies under a microscope. I kept accidentally squashing or over-etherizing them, and almost threw up. I had to leave the room when our teacher told us to etherize the rest.

In 10th grade occurred The Burning Crucible Incident. I had been heating some sample (don’t remember what anymore) for a while, and got some tongs to lift the burning-hot crucible. I clamped down, and lifted – and the crucible slipped and fell down the sleeve of my lab coat. I shrieked and started flailing my arm like a maniac. The crucible shot out of my sleeve at a gajillion miles per hour and soared through the air in perfect projectile motion, above everyone’s heads, before smashing on the floor by my teacher’s desk.

As I rushed to the sink, my teacher made my partner Max clean it up.

Good times.

A few years later, crucible-flinging me had become Me In My Last Year of Teenagerhood, and thrilled to find herself doing Real Space-Related Science at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

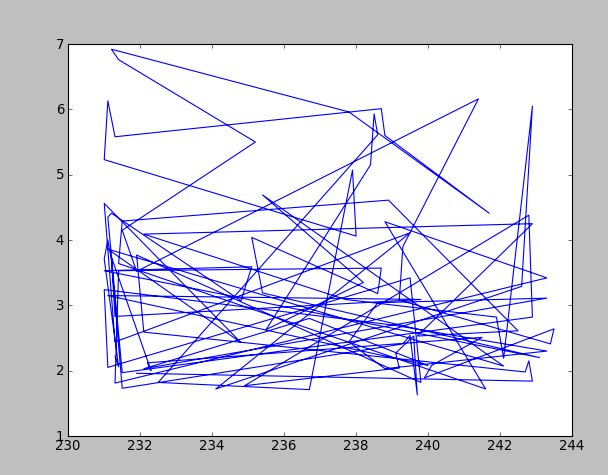

There, I learned that Real Science can also be ugly, although since all my work was computer-based there was a smaller chance of me flinging a burning crucible and killing someone. That feeling, when you finish writing a script, and are about to plot your data in a way that you hope will tease out some deep elegant meaning, and you triumphantly run your script in the command line, and see this:

NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

After 30-ish seconds of coronary arrest, I realized what was wrong (it was connecting dots it shouldn’t have been connecting) and sorted it out. I thought that my friend Eric would find this amusing, so I took a screenshot and e-mailed it to him. He was so amused that he put it on Facebook for the world to see, along with the caption “This summer, the world is training its next generation of people to unravel the mysteries of space. So far, they’ve found this piece of art :P”

Thanks, Eric.

Anyway, this obviously wasn’t a big deal – I just made a silly mistake. But I made a lot of mistakes this summer. My gaffes could fill a small treatise. On occasion, I spent three days charging down a line of reasoning before checking in with my mentor:

(you can hear how crazy this sounds already.)

One day during my first week, I stayed at work really late, and when my office-mate asked why, I told him it was because I didn’t feel that I had earned my hours for that day.

I also learned, after a week or two of thinking I must be the Dumbest Human Being Alive, that it’s not just me. One of my friends spent a week and a half fabricating a perfect piece of electronics, only to touch it in the wrong place and short-circuit it. Another friend once announced to his mentor that the substance they were testing didn’t corrode his sample AT ALL, only to be told that it had actually corroded an ENTIRE LAYER; he hadn’t been able to distinguish between the original surface and the newly-exposed one. At group meetings, I regularly saw graduate students stuck, going in the wrong direction, questioning whether what they had been doing for the past month or even more was at all useful. I saw faculty members and professional astronomers argue over the validity of a method or a result. I was surprised, although I shouldn’t have been – and part of joining their ranks was becoming comfortable arguing and defending my methods against their criticism.

“Arguing and defending my methods against their criticism” is a nice description of what Junior Lab oral exams are like. My professor in particular is very aggressive with the questioning, and in the 15 minutes of Q&A following my presentation on Poisson statistics, I got torn to shreds. Instead of defending myself properly, I just sort of stood there and let my mouth flap open and closed. The next time, I was much more prepared, mentally, although the preparation process was super stressful. The day before the oral, my result for the brightness temperature of the sun at the 21cm wavelength was: 70,000 +/- 140,000 Kelvin.

…

In case you don’t spot what’s wrong with that, let me give you a hint: error bars should NOT be an order of magnitude higher than the value. Fortunately, just like the plotting gaffe, I managed to figure out what was wrong and get my numbers to reasonable values. A few days ago, my friend and her lab partner measured the speed of cosmic-ray muons to be one point eight times the speed of light. Better than another friend and his partner, who took the class two years ago and measured the muon speed to be three times the speed of light.

Breaking physics is awkward.

As much as J-Lab is Experimental Physics bootcamp, it is also Dealing With Your Gaffes bootcamp. My section is at 9am-noon on Tuesdays and Thursdays, which may sound luxurious to you non-college-kids, but that’s about the earliest that classes start here at MIT – and I do NOT function at 9am. This exponentially increases the probability that I will do or say something embarrassing. In one of our first sessions, I tried to convince my partner Eric that multiplying by a really small number results in a really big number; he just stared at me until, thirty seconds into my explanation, I listened to what I was saying and facedesked. More recently, I tried to convince him that 1000 seconds was something like 3 hours, because 60 times 60 is 360*

*It’s not.

During our second experiment, Eric accidentally took out a sample before we were done – and we had to start all over again the next time. Weeks later, the two of us spent an entire section trying to get the microscope to focus, only to be told that we had the slide upside-down. Some of my friends have spent sections getting absolutely no useful data whatsoever – strictly speaking, this shouldn’t happen, because one should be analyzing one’s data as it comes in, but let’s be real – it happens.

And when it happens, your procedure is:

1) (optional) Be mortified for a maximum of five seconds

2) Laugh at yourself, and tell a couple of friends so you can lol about it together

3) Get over it

4) Try very hard not to do it again

Back to the summer, and the National Radio Astro Observatory, where I was fiddling with pulsars and felt a bit like I was making a fool out of myself. About two and a half weeks into the research program, I sent my supervisor an e-mail explaining a method I had devised to filter some pulsar candidates. I admit that I was sort of expecting the usual “sorry…what?” and was utterly amazed when his response was:

“Nice…That’s very cool.”

He gave some more suggestions, and finished with “Nice work with this!”

WOAH. Mind blown. And lesson learned: the excitement of coming up with something new TOTALLY outweighs the embarrassment of making a mistake. Gaffes are an inevitable, hilarious part of getting there. And make for good bonding with your J-Lab partner.