On September 24, MIT admissions blogging and His Holiness the Dalai Lama came together in the form of three Unread Message alerts in my inbox. The first, sent at 9:29am, was from Chris, saying that Emad and I had responded to his offer first and would therefore be receiving the Dalai Lama event tickets. At 10:00am and 11:28am respectively, an e-mail came in from Emad. The first – an expression of celebration at our respective ticket victories – read “YEAH ANNA HOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO”. I noted that this multiplied the length of my last name by 11.

His second e-mail read “Also, you’re ridiculous” and included a screenshot of my blogging archives that showed 8 posts in one month and ten days. I noticed that I had put almost all of them in the “Miscellaneous” category, and wondered if my posts ought to be a bit more topical.

I proceeded to spend two weeks freaking out about how lucky I was to have the chance to attend, and one week freaking out about the prospect of (in Chris’ words) “a cool media lanyard!” since apparently Emad and I had officially been granted “media credentials.”

What did that mean?

Pros: a sweet lanyard that said “PRESS”, a seat in the “press box” with journalists who assumed that I was another professional journalist (SCORE!), and the VIP/press line, that was approximately 100 billion times shorter than the regular audience member line

I felt super-legit

Cons: call time at 7:30am, and a seat right behind the film crews, which meant craning my neck to peek between tripod legs

The former meant bounding out of bed at the unacceptable hour of 6:30am. I stumbled around French House for a bit, bundled up, and shuffled to the student center for breakfast. Surprisingly, my only gaffe of the morning was to misunderstand the instruction to line “all equipment” down on the grass for a dog sniff security check. I didn’t consider my notebook, pen, La Verde’s bag, jacket, or copy of Mad in America to constitute equipment. I guess they did, though, since the lady in charge looked horrified when she saw that I was still holding my stuff; she freaked and rushed me to the far end of the tent so that I could deposit my belongings before the dog trotted over.

My bad.

After our “equipment” had been sniffed, we waited for another twenty minutes or so before being summoned to the metal detectors. The first team to go were the film crews – then the “writers”, which I was flattered to learn included me. We were led to the press box, and the still-photographers filed in behind us. The two directly behind me immediately began comparing the lens sizes they’d brought, in a language more alien than the Tibetan I heard from the Dalai Lama later in the day. I considered turning to the reporter on my left and announcing the length of my pen or surface area of my notebook or something, but she took notes on a laptop so we really had nothing in common. I read my book for an hour and a half (did I mention that showing up at 7:30am was ridiculous?) before being jerked out of my emotional trance (if you’ve ever read Mad in America, you’ll know what I mean) by the shuffle of all 800+ audience members rising simultaneously. I hadn’t even noticed them come in. I threw my book down and my body up, just in time to see His Holiness enter the room, flanked by about six security guards. His first move drew attention to his hands – he flattened his palms together in front of his chest, fingers to the sky. He grasped each panelist’s hands individually, bowing his head. He then walked, very slowly, to the front of the stage, and grasped the hands of each front row audience member in turn. Finally, he put his hands back together, looked out at the audience, and bowed to us, smiling.

Before I continue, I should fill you in on what this event actually was. It was different from the one Emad attended yesterday. Emad attended “Beyond Religion: Ethics, Values, & Wellbeing”, which consisted of a talk by the Dalai Lama followed by some kind of response. I attended “Global Systems 2.0”, which consisted of two 2-hour panel discussions – and, to be blunt, I enjoyed the second a lot more than the first.

The first was “Ethics, Economy, and Environment”, and whether it was because I had been sitting for an hour and a half by the time it started, or because I had woken up at 6:30, I found it very disjointed. Each panelist gave a ten-minute talk, followed by a “discussion” that involved a response from the Dalai Lama and possibly one other panelist, before the next presenter got started. It was late to begin, so the whole morning felt rushed; I think that it would have been more rewarding to have fewer panelists, and a longer discussion on each topic. Don’t get me wrong: the topics were interesting, but that’s why I wanted them to spend longer on each: it didn’t feel like any question was given justice. The overarching theme was climate change and resource management: questions were raised, and potential solutions described, concerning how to reach people who are deaf to the bad news about climate change, how to harness collective intelligence through crowdsourcing to come up with innovative solutions to climate change, and how to deal with limited resources when the population is spiraling (I guess a more mathematically accurate gerund is “being exponentiated”) out of control. I was hoping for a discussion on each topic that included the Dalai Lama, but rarely did anyone get to comment on the subject at hand, EXCEPT for the Dalai Lama. The format was essentially: 1) presenter describes one of the world’s great crises, as researched in his or her area of work, 2) moderator asks the Dalai Lama for comments, 3) the Dalai Lama comments, 4) repeat from (2), if time allows. That said, I can sympathize with the desire to hear His Holiness speak; I scribbled down some quotes to share with you.

“These environmental problems…we cannot see. By the time they can be seen, too late! We must take care…of our own world. There is no planet we can move to. All this must come through education…from kindergarten through the university level…must educate, educate, educate! (Earth) can live without us, but we cannot live without it.”

(Filling in an awkward pause, when the presenter had to stop so that the Dalai Lama’s translator could fill His Holiness in on what was going on*):

“As I get older, my English also gets older.”

*It would be really useful to have one of these to do the same for me during quantum lecture…

(Regarding getting the public on board with the global warming problem):

“For some people, receiving the message from religious leaders would be more effective.”

(After the presentation on crowdsourcing):

“Most of the ideas must come from experts!…their knowledge is much better. However, it gives people a sense of participation…(which is) very important. Then, in order to influence or impact…the government would be useful.”

And my favorite exchange of the morning:

Presenter: “I’ve spent my career studying a single species of phytoplankton, and the more I study it the more I realize we don’t know…anything.”

Moderator: “Is it possible that some of these problems are simply not resolveable?”

Dalai Lama: “Whether we can solve these problems or not…we have to make an attempt…every (government) wants to act in their own national self-interest, but if we all do that…all nations hurt. It is never black or white. Always middle.”

Presenter: “Yes, yes! We must always try. But like you said, it’s never black or white, so we must be cautious.”

A pause, as His Holiness leans inquisitively to his translator.

Translator mutters something.

Dalai Lama: “BAH!!”

Silence.

Dalai Lama: “Too much cautious, not good. Go ahead!”

Everyone applauds.

After the morning session, I booked it over to 6-120, the Physics department’s primary lecture hall. I sat through half of an 8.05 (Quantum II) lecture, before racing back to Kresge for the afternoon panel: “Peace, Governance, and Diminishing Resources”. The woman introducing the speakers mentioned that one of them – John Sterman – was nicknamed “Doctor Doom” by his students due to his thoughts on humanity’s future.

Great.

Despite these less-than-promising beginnings, I enjoyed this manifestation of the morning session’s topics a lot more. The separate talks felt like contributions to the same conversation: each presenter made reference to the others, and drew on elements from theirs to use in his or her own. The first speaker was Jon Foley, director of the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota. He said that “if John is Doctor Doom, then I’d like to think of mself as Doctor Happy”, then turned to ask His Holiness whether he had had a good lunch. “Yes, very good,” said the Dalai Lama. Just like that, the tone on stage was made much more casual; it felt like the panelists were actually talking to each other. Prof. Foley went on to say that 1/7 of the world’s population is currently undernourished, pointing out that “unless we follow (The Dalai Lama’s) advice and become monks and nuns”, population growth will continue to increase and our resources will continue to be stretched. He presented strategies for dealing with the problem, with the premise that current agricultural systems are terribly inefficient. “One liter of water”, he said, “goes into making one calorie of food.” He held up his water bottle. “One of these!!!” In his excitement, he dropped the bottle, which landed on the stage floor with a “thunk” and rolled away. The moderator didn’t miss a beat, suggesting that Prof. Foley is “on a diet”.

Good one.

At the end of the presentation, the Dalai Lama was asked for his comments, as in the morning session. He had a question for Prof. Foley.

DL: “There is huge gap between rich and poor…must raise living standards to what most of us are able to enjoy. If living standards are raised, is it [referring to Foley’s strategies for addressing the problem] still possible?”

Prof. Foley: “Yes.”

Pause.

DL: “That is good news.”

More gems followed.

DL (on the American tendency to over-eat): “Many years ago, I give lecture at Harvard. My driver…very fat. But always eating something.”

The second speaker was James Orbinski, a doctor who was President of the International Council of Doctors Without Borders when it won the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize. He started with a Charlie Brown quote:

then said that if John Sterman was Doctor Doom and Jon Foley was Doctor Happy, then he was Doctor Reality. He proceeded to describe “the gross and egregious inequity that divides our world”, drawing distinctions between humanitarianism and global health policy, and describing the harmful impact of climate change on health in third world countries, like sub-Saharan Africa. All this prompted a comment by His Holiness that we need to take care of the “physical level” – issues like hunger – before we can hope that people progress to the “mental level” of worrying about education, etc.

As if this didn’t paint a sufficiently bleak picture of humanity’s situation, Zeynep Ton – a professor in MIT’s Sloan School of Management and the third speaker – showed that a significant percentage of people have jobs that don’t pay well, let alone bring dignity to the worker. She condemned these jobs as “designed to be unfulfilling”, and honed in on retail jobs in particular, which involved flashing a picture of The Dalai Lama checking out some goods in a colorful grocery store aisle. His Holiness interrupted.

DL: “I like to see these things, I like to stop and look, because I think: “very beautiful!” Then I think: “I want to buy these things.” Then I ask myself: “is this absolutely necessary?” and the answer is almost always: “no.””

He got a round of applause for that one. I thought about the drink I bought on my way to 8.05 lecture that afternoon and felt guilty.

When Prof. Ton was describing the bleak working conditions that some face, His Holiness interrupted her a second time. He was indignant. “There are independent labor unions. So why? Why? There should be an organization that looks after these people.”

He got another round of applause from the audience; Prof. Ton didn’t answer his question, though. I think she was pressed for time. She went on to describe practices that companies can use to raise the quality of their employee experiences. At the end, there was a long pause, and finally His Holiness commented, very slowly:

“For many years I think…we need some kind of work body…representing nations…a higher body, made of the scientists, thinkers, retired leaders…who can truly represent humanity, not thinking about company interests, but the interests of the PEOPLE.” He then started speaking so quickly and fluidly that for a moment I thought I had lost my ability to comprehend English. Turns out he had switched to Tibetan. His translator chimed in: “His Holiness says that these challenges don’t seem to figure prominently on government agendas.” His Holiness took this as a cue to switch back to slower English. “We need experts…truly dedicated to the well-being of humanity. Truly dedicated to the well-being of seven billion people.”

The moderator asked if this was an accusation that organizations like the UN and the World Bank are not accomplishing what they exist for. His Holiness waved his hand and said “some other interest, national interest…figuring prominently. Now, experts can only make suggestions, or recommendations.” Back to the rapid Tibetan. According to his translator, he said that experts need to be put in positions where they can have a more direct influence on decision-making. At the end of his shpiel, he shrugged his shoulders, put his hands up in the air, and chirped “I don’t know!” with a big smile. He laughed.

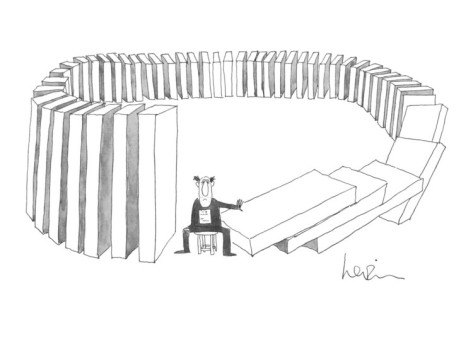

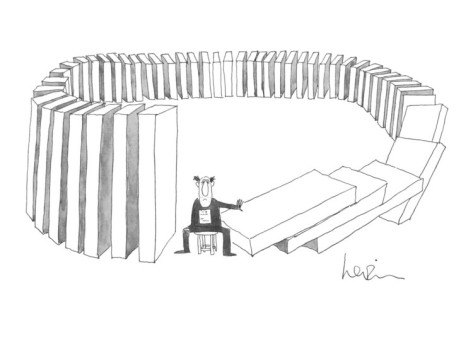

The final speaker, John Sterman, opened with a joke about the optimist and the pessimist. “The optimist,” he said, “says that this is the best of all possible worlds. The pessimist says ‘I think you’re right.'” After a pause and a translation, the Dalai Lama ho ho ho’d his amusement and the audience echoed him. Prof. Sterman suggested that all the other speakers had been describing SYMPTOMS of the fundamental problem: growth, both in population and in consumption per person. He emphasized the limitations of turning only to technology for solutions, pointing to the development of the atomic bomb and antibiotics as innovations with unintended consequences, with the following illustration:

He said that one problem is that people care less about earning enough money to be happy, and more about earning MORE money than other people. “This is a very big problem.” He looked out at the audience. “Everybody cannot be richer than everybody else. I can tell you that much. As we strive for that, we move away from what truly makes us happy, and destroy the planet in the meantime.” He displayed this very disturbing advertisement:

The advertiser’s suggestion, of course, is that you can fill the emotional void in your life by buying a very expensive pair of shoes.

At the end of Doctor Doom’s more-optimistic-than-expected talk, His Holiness said “I truly agree.” He said that when it comes to material development, one always wants more and more and more. “Now we need,” he said, “in education, the importance of…our MIND. This brings self-confidence. Maximum inner peace through inner strength. Ultimately, my feeling is – to educate people. Our weapon is truth: reality!”

And, like he did earlier, he concluded this very emotional passage by putting his hands up and chirping “so anyway, finished now!”

A monk from the Dalai Lama Center for Ethics at MIT got up and delivered some final words, encouraging us all to “demonstrate an unwavering sense of moral courage.” His Holiness placed white scarves around the neck of each panelist, bowing and clasping their hands one last time, before turning to the audience and bowing to us repeatedly as he sidled to the exit.

The image forever imprinted on my brain is not of the Dalai Lama, however. I can’t stop thinking about the violin performance that preceded the panelists’ entrance. A soloist played three beautiful pieces. After the first, he reached down with his left hand to adjust what I initially mistook to be a watch on his right wrist. He was having some trouble with it, and I thought it was a little rude of him to be so intent on checking the time in the middle of a performance. “As soon as this comes on,” he said, “I will play a piece called Meditation.” I suddenly realized that he wasn’t wearing a watch at all. He had a stub for a right arm, and there was a sort of clasp around his forearm and elbow that he was adjusting. The violin bow was somehow clipped onto that band. He had played so effortlessly that I hadn’t noticed. When he began playing again, my attention was glued to his stub as it glided through the air, back and forth and back and forth…I noticed that he had a very nice, white smile. As he walked off stage, violin tucked under his right arm and left hand raised in a wave, the audience put their hands together and clapped for longer than they did for the Dalai Lama.

I felt super-legit

I felt super-legit