MIT: REGRESSIONS by Ankita D. '23

a documentary on MIT, and why it's so important

MIT: REGRESSIONS is a feature-length documentary created by Luke Igel (’22) and Wesley Block (’22) on the history of the Institute, spanning from World War 2 to COVID-19. It uses 80 years of AI-enhanced archival footage to illustrate MIT’s place in the world and its swift rise to the pinnacle of technological innovation. Exploring several themes and arcs, it portrays MIT in a way that is familiar to students past and present, and yet wholly new and groundbreaking.

Upon its May 1st release, Regressions had a tremendous impact across campus. Understanding the historical forces that shape the institutions we have today is monumental in viewing MIT with more nuance, and I noticed students in my periphery taking more ownership over their student experience. Seeing how past students at the Institute engaged with campus and the world made us feel impassioned about changing aspects of student life we aren’t satisfied with, driving us to realize that we don’t have to embrace current norms as the default. This school is constantly evolving, and as it stands, students have the power to make their voices heard in a way that benefits communities both local and global. All it takes is awareness and the desire to enact change.

MIT has long promised to engineer a better world. This film asks a simple question:

Have we kept our promise?

Makings

Regressions was inspired by the documentary HyperNormalisation, created by BBC journalist Adam Curtis. While on a gap year due to COVID-19, Luke came across the film and was struck by its breadth of archival footage covering decades of American and British history. Using footage of MIT, he created a two minute parody and showed it to his friend Wesley, who immediately wanted to write a script for it. They added narration, and the more footage they uncovered, the longer the script became, eventually reaching 100 pages and spanning eight decades.

wes and luke, both phi kappa theta ’22s

To make the movie, they went decade by decade, searching through all existing archival footage and poring over hundreds of hours of content. Since this was during the pandemic, they didn’t have access to MIT’s libraries and a lot of their footage was low quality. This spurred them to build an AI enhancement tool to colorize and upscale it.

In making Regressions, Wes and Luke found inspiration in past documentaries about MIT. A 1969 film called MIT: Progressions01 shoutout to the amazing archival detective work of undergrad Kenny Friedman '17 captures student life in the late 60s, a time at when the student body was becoming more diverse and the Vietnam War protests were at their peak. It had beautiful footage of students walking around campus, taking classes, and discussing student government and the political turmoil due to protests happening at the time. Luke and Wes sought to capture a similar vibe in their film, but across all 80 years of MIT history.

They also used a film called The Social Beaver, created by Oscar H. Horovitz (‘1922) in 1956, one called Technology from 1934, and MIT: The Movie from 1992. Strangely enough, a film about MIT seems to be made every two decades. It seems only fitting that Regressions comes in 2022, in the wake of immense social change caused in part by the pandemic.

Music

Finding and putting together 80 years of footage is already a colossal task, but curating a fitting soundtrack is even more challenging. Wes and Luke did a phenomenal job—I can’t count the number of times I got chills, or that the room Regressions was streamed in became deathly quiet following a poignant musical moment.

The intro song, The Vanishing American Family,02 also used in <em>HyperNormalisation</em> sets the tone of the documentary incredibly well, and the use of Radiohead’s Everything In Its Right Place post-9/11 provided a somber transition from the 90s to the 2000s. Fall Down by Crumb is one of my favorite songs, so I was startled and thrilled to hear it in the beginning of the 70s, which I found fitting.

A particularly memorable moment was Doses and Mimosas in the background of a compilation of footage of my dorm. My floor has played that song non-stop since my freshman year, so it has a special significance to me, and hearing it alongside imagery of the dorm I love made me emotional. It’s a silly college song, but it reminds me of people I love and moments I cherish, and the energy captured in the Regressions clips felt all-too familiar.

Regressions spans dozens of threads, including MIT’s relationship with military research and the government, its presidents and leadership, its role in shaping Cambridge history, and its immense contributions to humanity. Luke and Wes planned to explore MIT’s involvement with the military from the beginning, and everything else came naturally from the footage they encountered. The result is a 3.5 hour film that delves into a different theme in each decade, painting a picture of MIT that resonates with students while presenting the institute they know and love in a completely new light. It’s incredible, and in my eyes, essential.

The Road to Release

regressions posters in the infinite corridor

some of my living community at the screening (featuring a slightly obscured me)

Experiencing Regressions

mit students with President Wiesner (1969) – source: the November actions by Ricky Leacock

Around the 90s, the film’s viewpoint becomes more MIT-centric, and the discussion centers around student life. I was shocked to see how much things have changed since then. MIT’s student culture is what made me want to go here, and the community I’ve found has been the most crucial part of my experience. However, the ability of students to self-organize and uphold their traditions has shifted radically in the past few decades. Living groups that championed self expression have since been eradicated, and many students today don’t even know about their existence.

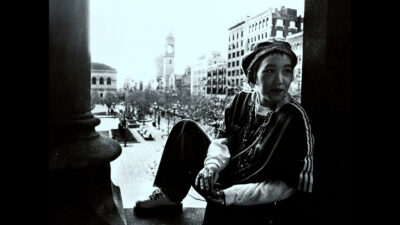

an east campus resident in copley square

Today, there are groups who continue to maintain their traditions, building massive forts in their courtyard, holding the same decades-old parties, and doing crazy, creative shit that makes campus feel like home. Less of these communities exist, though, and it’s painful to see what campus life used to be like when there was more space to be “weird” in the way MIT students are so often characterized. Times have changed, but student culture is what drew so many people to this school, so it hurts to see how much these ideals have been compromised.

Another aspect of student life that’s different now is activism. In the 1960s onward, MIT students went from being apolitical to being intensely engaged, and have since reverted back to their distant stance. I blame this partially on the internet, which both desensitizes us and provides us with a medium for discourse outside of interactions with our peers. There’s also the influence of yuppies and careerism in the 1980s, which brought greater focus to personal material gain and made flooding hallways and streets in protest seem like an aberration. Since then, students have been increasingly conscious about assuming risk, especially when everything is online and future employers are privy to any activity on campus.

mit students protesting near the draper instrumentation laboratory, known for its crucial technological role in Apollo 11 and the Vietnam War (Nov. 1969)

Although I understand why things have changed, seeing how robust student life at MIT was sparked a visceral frustration about current restrictions imposed on communities. After all, it was only recently that administration started making changes to student life, which made me wonder what it would be like to be an MIT student a decade prior. I bemoaned the loss of counterculture dorms like Bexley Hall, where I felt I could have thrived if it still existed. I was drawn to how free-spirited the residents seemed, how spontaneous and close-knit the community was, and most of all, the extent to which students could engage with their living space. Sadly, this partially stemmed from the dorm’s shitty infrastructure, which is what led to its eventual demolition.

![]()

At the time of the first viewing, my living group was scattered across campus due to the renovation of our dorm, Burton Conner. Seeing footage of the dorm in previous years was heart-wrenching since I haven’t been able to live with my community for the majority of my time at MIT. The last section of the film made me even more emotional; it depicted students’ reaction to COVID-19 and the pandemonium that ensued on campus shortly after. This hit me hard since I was a freshman during the onset of the pandemic, and the chaos of MIT shutting down was overwhelming and distressing beyond belief. Leaving campus stripped me away from the community I cherished so much, and being a college student during isolation was awful. It was tragic to witness how much student culture mattered to students across history and then think about how forces beyond my control affected my ability to engage with campus. I left 26-100 in tears.

Regressions covers a vast range of themes, but the content in the final cut is only a small fraction of the archival footage that exists. While much of MIT’s history is left untouched, the film helps students glean an understanding of what it means to attend this institute, and what it’s meant for students in the past century, who lived in the same dorms and took the same classes as us. We can walk away with more context about the elements of our current experience, why they exist, and what we can do to better them.

The Death of Student Life at Stanford

A few weeks after watching Regressions, I read an article titled “Stanford’s War on Social Life,” which describes how Stanford’s administration has destroyed residential life in the past ten years. In an effort to reduce liability and increase equity, the administration dismantled the social distinction that enabled so many students to find a home on campus. They scrapped decades-old traditions, drove student groups out of their houses, and then erected a homogenous housing system in place of it. The non-conformist, unique groups that used to live in houses with vibrant murals and ever-active lawn parties are now gone; their former residences are now quiet and have generic names and white-washed walls. The spontaneity and individuality that flourished on campus was thoroughly eviscerated. Now, students are sorted randomly into uniform dorms, where they struggle to find community05 This article paints an overwhelmingly negative picture of social life at Stanford. I have more than a few criticisms of it, namely the lack of acknowledgement of the harm Greek life can cause, and the notion that poor mental health is linked to the suppression of social distinction. Students at prestigious universities undergo tremendous amounts of stress, and finding community can ease the pressure they are subjected to, but cultural specificity can isolate people as much as it can include them. within arbitrarily atomized social units.

Stanford’s new social order offers a peek into the bureaucrat’s vision for America. It is a world without risk, genuine difference, or the kind of group connection that makes teenage boys want to rent bulldozers and build islands. It is a world largely without unencumbered joy, without the kind of cultural specificity that makes college, or the rest of life, particularly interesting.

Strangely enough, although this article was about another school’s experiences, it affected me quite a bit. In the months post-Regressions, my resentment about MIT’s waning student culture was fresh, and I was horrified to see how much other schools suppressed their residential life. Student culture both drew me to MIT and has been integral to my experience here; the support structures I have all stem from the community I’ve found, the community characterized vividly by the article. The spontaneity, the “wild unfettered joy,” the desire to interact with the world in the way you want to, the agency to create your own norms and culture…all of these things resonate deeply with me.

The article focuses on the loss of Greek life, but through further research, I learned the greater extent of which student culture was stifled. In the name of managing risk, administration suppressed students’ ability to self-organize, pulling resources from anything perceived as a liability. In addition to the sanitization and elimination of living groups, campus traditions were dismantled one by one. Even the archery club was shut down.

The new housing system, designed to promote ‘community,’ is more manufactured and artificial than inclusive. It wrested agency from students and isolated those who would have found home within cultural houses or co-ops.06 cooperative houses, student managed residences Now, Stanford’s social life is a shell of its former self.

The Evolution of MIT Student Culture

Since student culture is so important to me, both before and after the release of Regressions, I’ve taken every opportunity to learn how student life at MIT has changed over time. In discussions with alumni, it’s become apparent how different07 Random note: a friend who graduated in 2013 told me that dining used to be a la carte. Fresh sushi was $2 and sandwiches were under $5, so a meal cost only a few bucks. Now, under the mandatory meal plan system, students are allotted a set number of meals, paying up to $3,500 per semester even if they don't use all their meal swipes. To pay at the door, lunch is ~$16 and dinner is ~$19. This is why I've opted to cook for myself throughout my entire time at MIT—I'd rather manage my own groceries and pay $8 for Chipotle if I don't feel like cooking things are now.

In the past, MIT had a strong relationship with the local community since our facilities were accessible to everyone. Cambridge and Boston locals would host art events in classrooms, attend LSC showings, and participate in Mystery Hunt alongside students. Access to free space bolstered the local art scene and fostered better relationships between students and the greater community.

For me, the most hard-hitting example relates to the waning MIT dance scene. I recently heard that dance crews would practice and freestyle in Building 36, which has dozens of massive windows that serve as mirrors once it gets dark. I found this building early into my freshman year and would dance there to take a break from hours of psetting; it swiftly became one of my favorite places on campus. Hearing that much of Boston’s krump, popping, and breakdancing scene has roots in this building is crushing, as I never got the chance to engage with this community.

While I don’t know how much the loss of this building impacted the Boston dance scene, I have personally witnessed MIT’s fading relationship with the greater dance community. Due to the pandemic, local studios closed down, so students lost avenues to take classes, learn about different styles of dance, and train alongside locals. Now, the entire culture of MIT dance is different, and in my eyes, much worse. I can only wonder what things would be like if Building 36 was still open and students had exposure to the Boston dance scene.

As Regressions makes very clear, MIT has been a major driver of gentrification in Cambridge. While it may be impossible to ameliorate the harm this institution has caused on the local community, opening the doors of campus to outsiders would have a tremendous impact.

MIT’s dynamic with Cambridge and Boston isn’t the only thing that’s changed—in the past decade, the range of diversity within residential life has been diminished. It’s painful to hear the experiences of alumni who lived in communities like Senior House and Bexley Hall, which were eradicated. Students in these dorms could access their roof whenever they liked, furnish their rooms with lofts and furniture of their own making, and paint sprawling murals in the hallways on a whim. They also enjoyed less restrictions on social life, so they had more freedom to host events without having to be wary of scrutiny.

the 2008 Bexxxley Roxxx Some More concert, which took place in Bexley’s basement (source: the Tech)

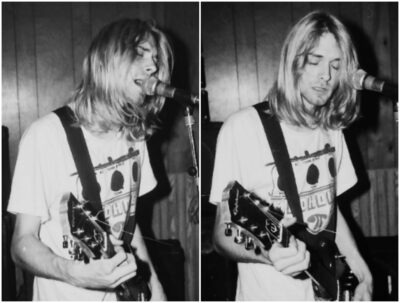

Kurt Cobain of Nirvana performing at Senior House (April 1990)

Senior House, which was eradicated in 2017, is MIT’s oldest student community. Since 1963, residents have hosted Steer Roast, a weekend gathering of current students and alumni that features live music, mud wrestling, and a giant festive meal. The first Roast in a couple years took place this April, and while it was amazing to see the dozens of alumni that returned to campus for the occasion, it was clear that the tradition is not what it used to be. The ceremonial lighting of the barbeque pit is no longer sanctioned, and Senior House is now grad housing, so the live music and courtyard partying pictured in the video below had to move elsewhere.

Today, Senior House and Bexley no longer exist, and in their wake, there are fewer free-thinking and experimental communities. It makes sense—whenever a group goes down, there are less people to fight for the other ones.

As organizations fall away, any remaining exuberance feels like an aberration, an unnatural imposition on the status quo.

Impact

I’ve heard a lot about the struggles my living group has faced in our 50+ years of existence. We’ve adapted to meet the circumstances, and have retained a lot of qualities that defined the community in the past, but it’s unquestionable that restrictions, particularly those after 2010, have affected our ability to function in the way we want to. The same goes for communities across campus.

It’s hard to discern why administration is limiting certain longstanding traditions. For example, mural culture is steadily being restricted; after renovations taking place in the next ~5 years, all dorms will no longer be designated as mural buildings. While students and members of admin have worked together to establish measures of preserving mural making, students can’t paint on walls anymore, nor can they paint on the largest possible removable canvases. In the new Burton Conner, there are guidelines designating the size and location08 according to fire code, canvases can only cover 20% of a wall. wall sizes also vary and are way larger than you think, so we're severely limited of canvases permitted in the hallways, and students have to receive approval on their designs before painting. It’s a far cry from the mural practices of the past.

I’ve been on Burton Conner’s renovation team for three years, and I still don’t understand why mural culture is being suppressed. I’ve heard various opinions from administration: “murals ostracize summer residents of Burton Conner”; “with white walls, no student will feel excluded.” These statements always seemed nonsensical to me, as the murals in Burton Conner are what made it feel like home to so many residents.

An empty house is safe. A blank slate is fair. In the name of safety and fairness, Stanford destroyed everything that makes people enjoy college and life.

Walking down the halls of Burton Conner and seeing the blank white walls is nauseating. We’ve tried to work around restrictions, making murals out of painter’s tape and adding colored filters to the lights, but some of these measures are taken down and thrown out for violating fire code. I can’t help but miss the way things were in my freshman year.

i miss the orange and black walls and tiling & the dingy, lived-in feel of this. there was so much personality that’s now gone

taken right after we moved in this year

Stanford students live in brand new buildings with white walls. We have a $20 million dollar meditation center that nobody uses. But students didn’t ask for any of that. We just wanted a dirty house with friends.

I don’t know why many of the facets of social life that students value are disappearing. I know that administration works within their limits, and we work within ours. Sometimes, restrictions are necessary; other times, they are the result of heavy-handed liability avoidance, and aren’t conducive to cultivating the student life that MIT prides itself for.

Stanford has become a case study of how overzealous bureaucrats can crush natural social expression, and how the urge to excise danger can quickly devolve into a campaign to whitewash away anything remotely interesting.

In my time here, I’ve been a part of multiple communities where it is accepted and encouraged to interact with your environment, to be comfortable within your living spaces, to exist without shame. I’ve been continually surrounded by individuals who question conventions, refuse to just live within their confines, and seek out norms that provide them with the greatest fulfillment possible. These individuals are some of the funniest, most intellectually curious people I’ve ever met.

In all my involvement with student government, I’ve fought to preserve this part of MIT’s personality—the part formed by irreverent, quirky people who don’t give a fuck about what’s normal and what’s not. The people who paint murals and build massive wooden rollercoasters and live carefree.

Counterculture—”weird” kids, painted walls, pride flags—is what attracted me to MIT. While you can find students like this at any school, MIT was the only place with a whole dorm of us. I came to MIT because of East Campus: a community where I could explore, create, and feel not just safe, but celebrated. When MIT destroys these dorms, MIT writes me out of its history and its future. Watching Senior Haus, Bexley, Burton-Conner, and soon East Campus get shut down or gentrified beyond recognition makes it hard to imagine students like me coming to MIT in the future, and more subtly, it feels like MIT saying, “We don’t want you here.” – Simon R. ’24

a rollercoaster built by east campus residents in their courtyard

I graduate at the end of this year, which means I have a few months left to shape the trajectory of Burton Conner. Before I leave, I want new residents to understand what it entails to be a part of a dorm with rich history and traditions, and what it means in the broader context of MIT student life. That’s why I pushed underclassmen in my living group to attend the second screening of Regressions—I wanted them to see footage from communities like Bexley and Senior House to understand why exactly they should care about preserving student culture. If they resonate with the values they see and resent the way things are now, I hope they can embrace nonconformity and the freedom of expression in spite of living in a space with so many limitations.

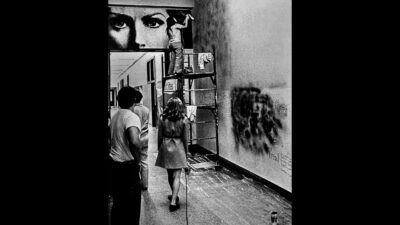

a group of students painting murals in the infinite corridor. who knows whether they asked for permission

MIT used to be sterile; in the early 1960s, the Infinite Corridor was grey, and counterculture was practically non-existent. All it took was a few groups of students to breathe life into campus, creating enduring culture and shaping it to be the place that attracted me, my peers, and all those who came before us.

Things have changed since then, but time and time again, students have worked to preserve what they love—who’s to say future generations aren’t equally capable of achieving this?

Moving Forward

It’s easy to mourn how much things have changed, but a lot of what’s happened has been inevitable. The pandemic had a drastic impact on everyone, not just student communities, and we will continue to feel its effects in years to come.

On the administrative end, the perceived assault on MIT’s cultural heritage arises from many factors, many of which will never be clear to the student body. What’s evident is that there is a lot of liability associated with allowing students to modify their spaces and have total autonomy over their living groups. Cutting down on residential tradition, limiting self expression, and randomizing housing would solve a lot of problems, although it would be antithetical to MIT’s values. While there are many administrators who support students and defend their right to protect residential culture, a select group—as discussed in Regressions—have consistently tried to diminish and even abolish that things that make MIT the way it is.

As much as students can attempt to fight these changes, we all have only four years here. Longevity comes from a transfer of institutional knowledge, and when that’s disrupted, as it was during the pandemic, cultural continuity is even harder.

If I had it my way, every student who feels a connection to MIT’s student culture, regardless of what that means to them, would watch Regressions. Even if they’re satisfied with the way things are now, I hope they can see what student culture has provided their peers so they can support them as they navigate changing restrictions. I want future students to understand that, in some ways, the idealized version of MIT they hear about isn’t really how it is these days, although they can change that. Student culture is by no means dead, just adapting to recent changes, and if there’s anything MIT students are good at, it’s finding creative ways to do what they love.

The current president, L. Rafael Reif, is stepping down at the end of the year, and there are a handful of people in student life administration who are leaving as well. I can only hope that those who replace them demonstrate respect for their predecessors, appreciate MIT’s traditions, and want to preserve what makes this school so unique.

After I graduate, I hope living communities will continue to thrive, and that the administration will bear the responsibility of sustaining a campus where students can find their niches. How this trend of student life continues is up to all of us: will administration let MIT become like other colleges, and will students rise to protect what they love?

80 years.

100,000 alumni.

Trillions of dollars.

What started as an idea, to better the world through technology, has become the gold standard. Through the tireless work of generations of extremely talented people, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has grown from a patch of dirt into a city on a river.

And yet, with all our talent, and all our resources, the pandemic brought this institute to a halt. Already, MIT has demonstrated remarkable resilience, and it is clear that the Institute will survive.

But it will not survive unchanged. Living groups and student clubs do not have billion-dollar endowments. Which of them will survive? And if they die, what traditions will we lose?

What will take their place?

As students return to their labs, what research will we conduct, and who will fund it?

As we recover our balance and march on to progress,

who is MIT going to be?

- back to text ↑

- also used in HyperNormalisation back to text ↑

- an 80-year old organization that hosts movies and screenings in 26-100 every weekend during the school year back to text ↑

- this was President Wiesner, who was explaining how MIT tried and failed to create a medical school in the 60s. the way he was talking to the students was so candid..i can't imagine having a discussion with the current president in this setting & manner back to text ↑

- This article paints an overwhelmingly negative picture of social life at Stanford. I have more than a few criticisms of it, namely the lack of acknowledgement of the harm Greek life can cause, and the notion that poor mental health is linked to the suppression of social distinction. Students at prestigious universities undergo tremendous amounts of stress, and finding community can ease the pressure they are subjected to, but cultural specificity can isolate people as much as it can include them. back to text ↑

- cooperative houses, student managed residences back to text ↑

- Random note: a friend who graduated in 2013 told me that dining used to be a la carte. Fresh sushi was $2 and sandwiches were under $5, so a meal cost only a few bucks. Now, under the mandatory meal plan system, students are allotted a set number of meals, paying up to $3,500 per semester even if they don't use all their meal swipes. To pay at the door, lunch is ~$16 and dinner is ~$19. This is why I've opted to cook for myself throughout my entire time at MIT—I'd rather manage my own groceries and pay $8 for Chipotle if I don't feel like cooking back to text ↑

- according to fire code, canvases can only cover 20% of a wall. wall sizes also vary and are way larger than you think, so we're severely limited back to text ↑