Designing MIT for democracy by Chris Peterson SM '13

why is MIT so decentralized and chaotic? BECAUSE DEMOCRACY

While reading Whitney Zhang’s article in the Tech on the history of the first-year experience, I stumbled across the following graf quoting the legendary Debbie Douglas, director of collections at the MIT Museum:

Furthermore, Douglas wrote, at the time there was an “existential issue regarding the real and perceived threat of fascism.” Faculty found that course curricula were similar to that of a Soviet university and that “the kind of student MIT was educating was being trained to conceive, design, operate, and manage large technological systems that had the same centralizing tendencies as did communist governing systems.” As such, there was an increased emphasis on the preservation of democracy through civics and the humanities.

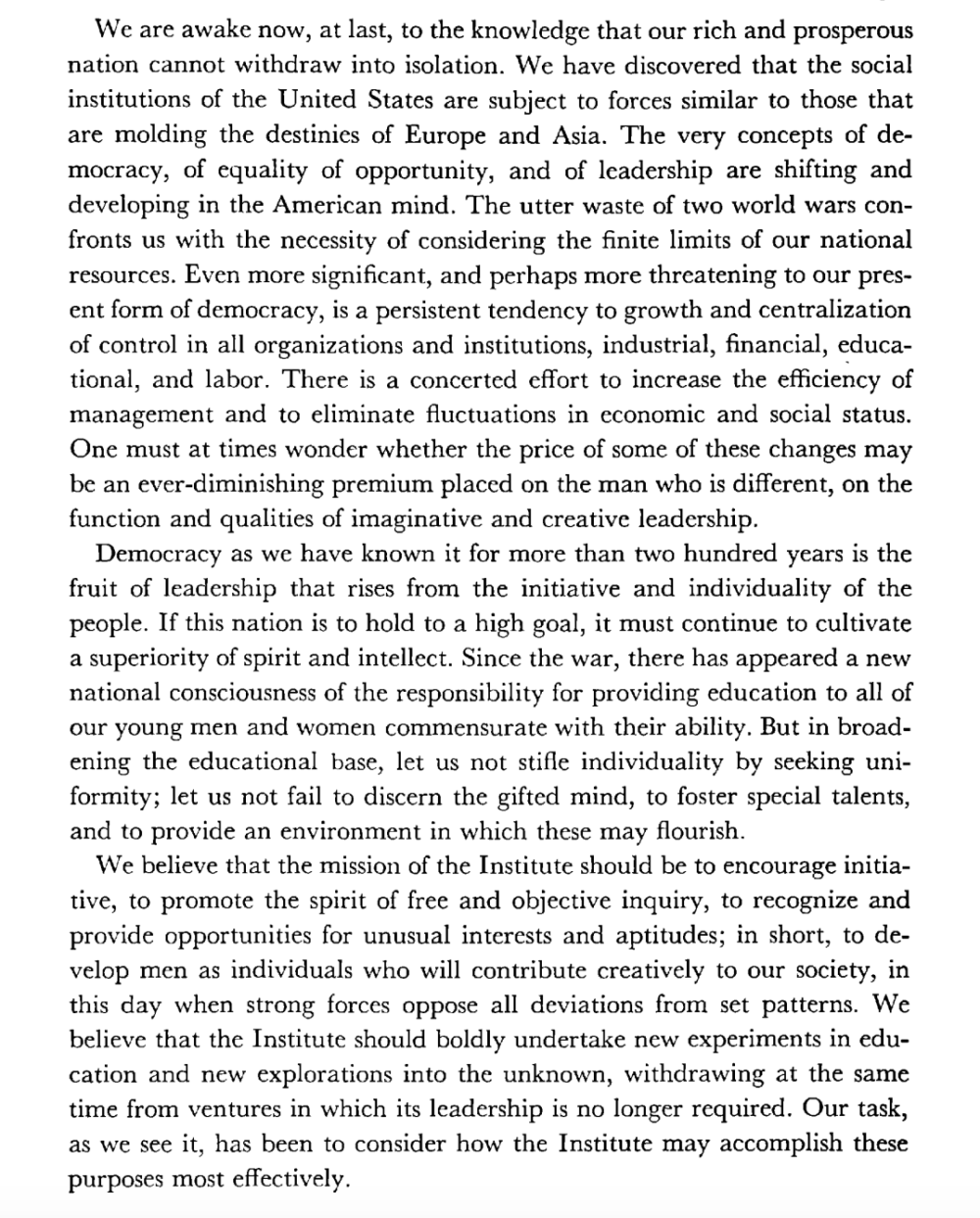

This jogged my memory from the introduction of the Committee on the Education Survey (aka the Lewis Report), which, as you can read on our history of MIT page, was the most fundamental restructuring of MIT in its history, establishing, among other things, the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Science. The report, written in the historical context of WWII and the Cold War, and the educational context of questioning the role of a private university in an era of well-funded public universities, explicitly foregrounds these concerns in discussing how the MIT education, and the Institute writ-large, ought to work:

I’ve long loved the latter two paragraphs in terms of what makes MIT different: this emphasis on providing for unusual interests and aptitudes, for me, is the core goal not only of MIT, but for what has long been (more problematically) called “gifted education” for decades.

But I hadn’t fully realized the implications of the first graf, particularly the warning regarding the “persistent tendency to…centralization of control in all organizations and institutions,” including educational institutions. With the extra context from Debbie, I read this as arguing not only the curricular content, but the organizational form and institutional culture, of MIT was historically designed to advance a democratic agenda.

When people ask me what MIT is like, I always talk about how it’s decentralized, even disorganized, and how students have almost unparalleled autonomy, because we believe the way you teach people to be responsible is to give them responsibility. As Stu wrote in the spring regarding contemporary student activism:

We also believe that civic responsibility is, like most things at MIT, something you learn best by doing: indeed, to be civically responsible is to put into practice the obligation we owe to each other and to the common good. At MIT our students govern and manage their residences, serve on influential committees that inform Institute affairs, make policy recommendations to serve social goals, and, yes, protest, at the local and national level. They’ve done all these things for generations. Indeed, the broad autonomy awarded to — and the responsibility expected from — MIT students is a core feature of our educational mission and culture: we hold our students to a high standard and give them a wide berth.

However, this reading of the Lewis Report gives even more context to these longstanding aspects of our culture and organizational form. So from now on, when people ask me why our students have so much freedom to pick their dorms, or why we don’t force people to apply to a program and stay there, or why none of our websites look the same across the Institute, and why so few things at MIT run “from the top down,” I will proudly answer: because democracy.