Food for Thought [guest post] by Amber V. '24

On food and our culinary club, Mince

by Tananya Prankprakma and Sophia Wang

This post is a love letter to food written jointly by me (Sophia) and Tananya.

I’m Sophia, the past head and creator of the Massachusetts Institute of Culinary Experiences (MINCE),01 Check out mitmince.com and @mitmince on Instagram to learn more about our events, recipes, team, and general thoughts on food. (PS: Even we’re a little confused about the stylization of our club name. But we love the feel of 'mince.' It’s an action that often marks the start of a recipe, and by that understanding, 'mince' is an act of creation.) a culinary group on campus. Tananya is the current head of MINCE. I started this organization to create affordable dining experiences run by students, for students. Hosted at unique locations within MIT and beyond, these culinary pop ups are meant to serve both as a creative outlet for students interested in the culinary arts as well as an intimate space for students to form meaningful connections around the dinner table.

Our hungry, ever discerning MINCE cat

The original intention of this blog was to expose more people to our organization by presenting the goal of MINCE and (attempting to) explain why we care about it. This itself was like finding yourself at a meadow, and having to explain why you enjoy it. Certainly, we still hope to achieve this message during the blog, but its driving pulse has since shifted to understanding why we ourselves are drawn to food, and through which mediums we’ve chosen to pursue that awe. Some of these include MINCE, others do not.

Sophia

Saying I grew up on food is no less obvious than saying I grew up on air. I needed it, both literally as sustenance and fundamentally as a gravity, a first principle to found my life upon. I’m not sure when it started and meditating on how and why would be unproductive. The truth is likely as simple as noodles slathered in chili flakes and green onions, a ladle of hot oil tumbling down, aromatics alive and well. Revolutionary. My love for food, this desire to cook — I found myself in the middle of it and holding a bowl of yogurt, drizzled with honey, a stray handful of raspberries. I haven’t yet found a way out.

Like most members of MINCE, my love for food feels more like an instinct, a second first nature, than any cause-and-effect relationship or line of logic. Among the few belongings I hauled to campus my first year of college was a cleaver carefully wrapped in a microfiber cloth. Most of the media I consume explores food in one form or another, whether that’s documentaries on world class chefs like Vladimir Mukhin and Nancy Silverton, or a short form Instagram series on compound butters. The one notebook I’ve kept consistently is a recipe ideation book.

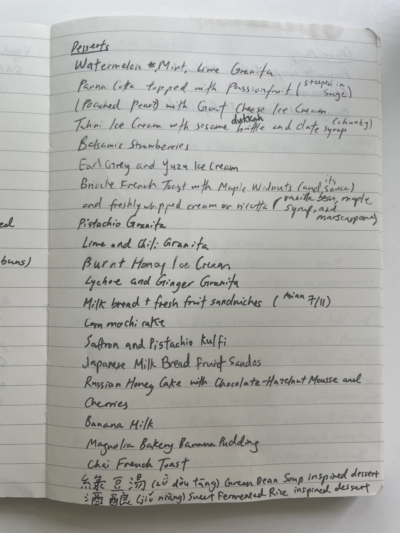

A recent page

I knew, certainly, that there was a reason I was drawn to food, but the thrumming instinct to be involved with food occluded any desire to spell those reasons out, taking with it any clarity in the process of untangling. More than that, the expression of something so important was difficult — something simultaneously obvious and impossible to put a finger on.

I first hit something during the fall of my junior year with my friend Kenny, a recently graduated ’23. He is a brilliant biologist, statistician, musician, the list continues. He is intentional, kind, intelligent, and raucously funny. Though Kenny does not pursue accolades, he has an impressive body of research and awards. He could easily (and humbly) find himself at any institution post-graduation. Instead, he will be moving to Kansas City one week after graduation with a two-year contract with Teach for America, teaching biology to high school students. After those two years, if he enjoys the work and the district, he will consider staying.02 I don’t include the previous details to perpetuate a ridiculous conclusion that because someone is well-educated at an institution like MIT, their goal must be to climb the ranks at even more elite institutions. I include it to illustrate a freedom of choice and diversity of opportunity that few people have access to, making his decision all the more thoughtful.

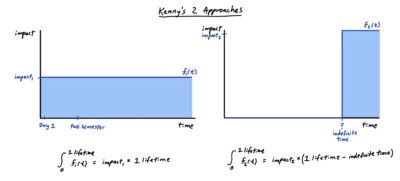

I asked why he chose teaching among his competing interests of research and academia. He explained with an integral.

Teaching has an undeniable impact. It was the surest way, with his skillset, to make an impact every day on the twenty or so students that sat in his classroom. Doing that every day for years, he reasoned, was like integrating across a flat line (for the more scrutinizing eye, a unit step function). His career would have a reliable impact.

Whereas working on, for example, a research project is analogous to integrating a pulse function, or a right/time-shifted step function. Projects like these have high yield at success, but there is no guaranteed success.

There is clearly no best approach. Both must exist for a functioning and progressing society. However, his explanation acknowledged the fundamental importance of daily impact, something rarely accredited at MIT. MIT is an ecosystem of buzzwords. “Finding the next…”, “Breakthrough in…”, MIT is discovery, invention, and innovation. We are lucky to be in a place that enables us to pioneer the next novelty, but amidst this culture, you can easily lose your grounding.

In short, how we treat one another each afternoon, our daily services to our community, accumulates to reliably enormous significance.

Admittedly, rolling out tortellini on a Sunday morning for a friend, obsessing over the perfect acidity for a salad dressing, losing my mind over the set of a panna cotta, and claiming this was all important sometimes feels silly. However, I could not shake that feeling and at last he had given me the words.

More than an art, cooking is a service. Go one level further— what we cook is sustenance. There are few activities which are repeated so frequently and with such casual import. We have two to three meals daily, and we should get to enjoy those meals. Small changes to our attitude towards and preparation of food add up tremendously.

I feel privileged to cook for myself and especially for others. Participating in someone else’s ritual and on occasion elevating that ritual feels analogous to being let into someone’s most sacred habitual life, a fly on the (kitchen) wall. A meal is ordinary in the sense that it is common. A meal is also beautiful because it is so common. There is such latitude to experience food – all the flavors and textures, the sights and smells – because we eat often and with necessity.

I want to inspire joy through food, whether that’s a 15-minute ramen bowl or a meticulously orchestrated two-hour course. A meal may be ephemeral, but add it up — three times a day, 365 days a year, how many years in a lifetime? — and you’re left with something permanent, a lasting effect of care and love (because what is love if not the most consistent form of care?).

When food is posited only as the snack you eat in lecture, a trip to the dining hall before rehearsal — something fit in between the ‘actual’ events of our life — we forget the miraculous, life-giving fuel a meal is, and the nourishment food is capable of imparting. If anything is deserving of ceremony, food is surely a worthy candidate.

Well, what does this all look like in practice? MINCE is among my favorite examples. We are a 20-person team of students. Three times a semester, we host pop ups where we serve ~35 students, chosen by lottery, a 4-course menu priced at $17. Each menu is centered around a theme. I’ll expand briefly on two past events.

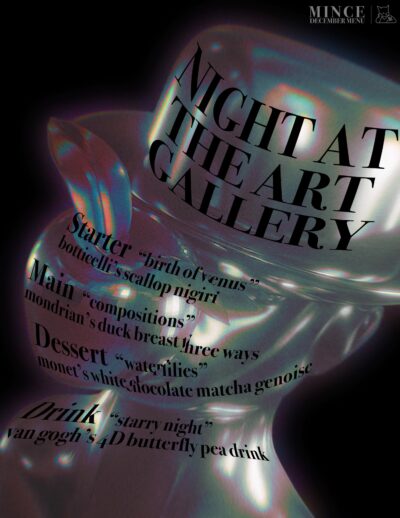

Night at the Art Gallery

Our goal with Night at the Art Gallery was to highlight the culinary arts by drawing parallels to well-known paintings and movements like the Renaissance period, Impressionism, and Neoplasticism. We wanted to transport our guests and challenge ourselves with modern gastronomy.

Our Night at the Art Gallery Menu

Our menu was:

(starter) “Birth of Venus” Botticelli’s scallop nigiri

(main) “Compositions” Mondrian’s duck breast three ways

(dessert) “Water lilies” Monet’s white chocolate matcha genoise

(drink) “Starry Night” van Gogh’s 4D butterfly pea drink

Our dessert team spent eight hours the Tuesday and Wednesday before our event working on tempering a white chocolate flower for each cake. They even made a computer-aided-design (CAD) model of the flower and CNC machined a custom mold at a maker space on campus. Our main was an aged, sous vide duck atop a honey glazed milk bread sandwich with a duck-fat potato puree. To complement the duck, we experimented with countless set gels, eventually settling on an orange-safflower jelly and scallion, chicken broth aspic.

But food is only one part of any meal. The company and the environment make up the rest.

Our lottery intentionally limits parties of guests to 2. We encourage students to come willing and excited to form new connections around the dining room table. Our reservation form from this event asked participants, “what would you study if you could major in anything?”

A few of their answers:

coffee brewing

electronic textile handicrafts

meteorology

furniture making

gestalts

chipotle menu design

We then formed tables with the responses, hoping to ignite chemistry and intimacy.

Our design team made over 50 balloon-animal dogs by hand, a reference to Jeff Koons’ famous stainless-steel sculptures. One per guest was placed at the center of each table. A bamboo reed was stuck between the arms of each iridescent dog to diffuse lavender, the fourth dimension of our drink course. The table runners were brown sheets of paper carefully striped with intersecting lines of color, mimicking the precise geometric forms and primary colors of the de Stijl art movement we would reference in our main. Look carefully at our menu, and you’ll find that the background is a CAD rendered model of a man with an apple obstructing his face, a reference to The Son of Man by René Magritte. Angela, our head of decor, even sculpted 3 clay pieces for the event–apples, progressively melting–which we positioned on stands throughout the room. The venue was a lecture room in the architecture department, but that night, our guests dined in an art gallery long closed. Mesmerizing and whimsical. Sacred in its secrecy. A tiny world created for the evening.

Romance through Film

Romance through Film was a Valentine’s Day event we hosted through collaboration with MIT Datamatch, a dating algorithm popular on campus. The event emphasized one of MINCE’s major goals: creating meaningful connections with food as the centerpiece. I asked myself before starting MINCE, “in the torrential firehose of life on campus, when do people have the chance to sit together unoccupied?” The answer was over a meal.

Our Romance through Film Menu

Our menu was:

(starter) Charcuterie cheese board

(main) Lamb ratatouille

(dessert, pt. 1) Apple rose tarts

(dessert, pt. 2) ‘Life is like a box of chocolates’

(drink) Love potion

Each was a nostalgic reference to the food from childhood films our team largely grew up on, from Shrek’s ‘Happily Ever After’ potion (our take is a raspberry syrup, strawberry jam, and pomegranate concoction finished with dry ice) to a humble vegetable stew that transported the vulturous Anton Ego. In an extravagant touch that very much embodies the attitude of MINCE, the cook team laser-cut and assembled custom wooden boxes for our guests. Inside, we placed a Bordeaux chocolate and a white chocolate and raspberry truffle. Engraved on the box was the message, “Life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna get. Love, MINCE.” The head chef of this event, Michael, wanted to use the romance of memory to comfort and delight our guests.

After service, we shared with him that as much of a pleasure the meal was for our guests, creating those courses had given our team a childlike joy we’d all missed dearly.

The decor for this event was simple and elegant. We booked a penthouse overlooking the Charles at sunset. Two talented friends of MINCE, a violinist/pianist and a guitarist, generously played our event. Our team focused on how to spark conversation between our pairs of strangers. We opted to create a deck of question cards, some taken from the New York Times’ 36 Questions That Lead to Love, others suggested by MINCE members.

A few of the cards are shared below:

Admit something.

What’s something you wish you could do for the first time again?

What would constitute a “perfect” day for you?

What do you wish you could spend more time doing?

I am constantly surprised by the vulnerability strangers can achieve. Events like this have emphasized to me that when we create a place where vulnerability is both encouraged and importantly, casual, people will seek that space out with eagerness and intentionality.

This summer, I worked part time at a cozy ramen shop in Porter Square, Yume Wo Katare. Yume Wo Katare translates roughly to an invitation: talk about your dreams.

The shop is no bigger than two dorm doubles (maybe a generous triple) and is arranged in three neat rows of six. At any time, there are no more than 21 people in the restaurant, including staff. The walls are covered in cartoons. Each depicts one stage of the chef’s journey to opening this fan-favorite spot, from the years he spent in Japan to his arrival in Boston. There is a sign, much like one you might find on the road, NO PHONE ZONE, then in smaller lettering, stay present. Look up and you’ll find a painted sky, baby blue. Clouds, fat and imprecise, dot the ceiling. Each is a dream.

Invent a patented design.

Travel the world by van.

Quit my job.

Even the chairs blend into this world of whimsy. The wooden backs of two chairs in the middle row read, THIS IS NOT JUST RAMEN. The second, THIS IS YOUR DREAM. There is only one item on the menu: pork tonkatsu. A broth so rich it looks almost murky, creamy from fat, some rendered, others still white, floating like icebergs in your bowl. Handcut noodles, chewy and jagged. Soft garlic, minced and preserved overnight, disappearing on your tongue just as it enters. The pork is salty and pink and has been braised for hours. Its fibers give way to the slightest parting of a chopstick. Delicious. When a customer finishes their bowl, a member of the Yume team will ask whether they have a dream to share. The customer nods and sets down their pair of chopsticks. The chef calls the attention of everyone in the restaurant. Even the noodles stop swimming.

He wants to build a log cabin in the woods and raise a family there. Stacked logs of cypress and moss, crisscrossing. Crickets chirping through the night (you hear them even with all the windows closed).

She is an amateur birdwatcher. Her dream is to spot a black-throated gray warbler, a rare bird found in the Midwest. She’s captivated.

“I want to grow old with my girlfriend.” She is sitting next to him.

“My dream is to publish a novel.” I know she will. The newest Brandon Sanderson sits on the table. I watched her thumb through it in line.

Inside the ramen dream workshop

When I was first hired, I exhausted Jake, the owner and head chef, with questions about his bowl. What determined the plating order of all the ramen components? What was the flour mix and ratio he used? How did he come to the perfect minced consistency for the garlic? I tried and tried to drill to the root of the dish he had mastered from his Sensei. He answered, but I could tell he wasn’t interested. “You have to understand,” he said. “I’m not interested in food. This isn’t a restaurant; this is a dream workshop.” I was stunned. “I create a good bowl of noodles, so people respect the dream workshop.”

I am obsessed with food. I want to understand the mechanics of food, its science and interactions, in a pursuit of knowledge that feels more instinctual than necessarily deliberate. In this way, our attitudes are markedly different. But his words ring true to me. They remind me of the service and the space food occupies in the people it has and will touch.

Among the people that food impacts, I want to emphasize that the service of cooking runs in both directions. In MINCE, as much as we focus on our guests, there is a special camaraderie built through battling with the kitchen. Most Friday nights before events, you will find the New House dorm kitchen and the adjacent conference room packed with members preparing pesto sauces, assembling banana leaf platters, julienning pickled radishes until well into the early morning. We’re fueled by our in-house barista, Haris, who at 11pm makes delicious instant coffee with hand-whipped cream. Michael once flew in a Thanksgiving pecan pie and roasted duck as a treat during one of our fall recipe and development (R&D) sessions. We listen to Tananya’s indie mixes. We go on roadtrips to New Hampshire’s White Mountains and Maine’s coastal cities for inspiration and retreat.

Without going out of our way to, MINCE has become a community of people who are as many parts passionate as they are kind and caring. A friend put it to me, “MINCE self-selects for people who would spend their weekends cooking for others.” I am proud of our members and lucky to call them my friends. As much as we create for our guests, who make all these events possible, we create for ourselves. The environment of innovation and friendship makes the delirious early morning hours, the frustrations over grainy caramel and burnt kulfis, part of an eager process for all of us.

At the first restaurant I worked at, a modern Southeast Asian restaurant named Bone Kettle in Pasadena, California, days off were rare but anticipated. Each time, we would drive to Las Vegas to stuff ourselves at luxury casino buffets, stop at Cane’s for Texas toast off the highway, rip through bags of pork cracklings, and enjoy each other’s company in the brief refuge from long days. I consider the team at Bone Kettle to be an extension of family, and the two constants through our relationship were good food and good people. Working there in California was the last word of encouragement I sought out to start MINCE with my closest friends, because, in truth, all I’ve wanted was good food and good people.

Camaraderie on the line at Bone Kettle

As for MINCE’s future, I am excited to see Tananya’s vision come to life. Meeting her, getting to know her, is like taking your favorite walk at sunset by the river. Like putting on headphones and that first flood of music which crosses into audible sound, the swelling of something warm. More than anything, Tananya is open to the world, its ordinary and extraordinary offerings, in a way I find both incredibly rare and fundamentally accessible. I have met few people with such earnesty and affect. We share similar and different beliefs towards MINCE, which you’ll read about shortly. She has the patience and nurturing eye to both recognize and coax out the beauty in her environment. Further, she is able to translate that into something special, imparting onto others that sense of awe which comes so naturally to her, others might call magic.

Tananya and I

I’m sure my understanding of food and my role in this vast ecosystem will change over time. This is my most complete, written understanding to date. When writing this blog, Tananya and I met many times to discuss. We were both struggling to commit pen to paper. She said, “how am I supposed to make every connection, when the words go in a line?” That’s exactly it. Like crumbs of bread scattered in my lap, the juice of a peach running down an arm…if I could explain the feeling with feeling.

Tananya

Hello! I’m Tananya, and I have just a few words I’d like to say. In my first draft, I actually had almost 2000 words to say, but after sitting on it for a month this is all I have left. Sophia has said most of what you need to know, so here is the rest.

I’m writing this little piece because this summer, the responsibility of making decisions that guide Mince has been given from Sophia to myself. There’s been a lot to think about. I actually don’t have much experience dining in cool and innovative restaurants, and growing up I never ate out much. I probably don’t cook any more than the average person that just wants to save money, though I do want to work on that this coming year. Also like many other people, I see food as a meaningful expression of love and care, largely because of how I was raised–with good food shared with good people. Love, regularly scheduled, dinner every day. I believe that food is beautiful, because if you’re lucky, you have no choice but to eat, over and over and over again. If you’re lucky, eating is something memorable, and food becomes another way to find joy in daily life.

In terms of joy, the other things I care about are pretty typical. I think the ways in which time is best spent boils down to only a few things. Being with the people I love, being with myself. Being with the outside world, seeking fresh air when possible. Reading good books, listening to good music, doing what makes me happy, whatever that entails.

I also tend to believe that the things I pay attention to, and the fact that I pay attention to them, has meaning. Light and shadows, the feeling of wading in cold water. Kids running around places where they shouldn’t, the greenness of summer in my hometown. As I learn more and more about what it means to be alive, I find myself wanting to capture and express something about my experience, even though I haven’t quite put my finger on it. In short, I would like to be a storyteller.

I decided not to post 2000 words because explaining why I care about the things I do, to borrow Sophia’s metaphor, was like I came to the edge of a meadow and had to explain why it was nice. I want to try to tell my story in other ways, and see what comes through.

I’m very happy to be able to call the people I’ve met in Mince my friends, and so grateful that Sophia started such a wonderful community. It’s a space where people can come together and share with each other, beyond food, what we love. Should you share a meal with us, we hope that you can feel that love as well.

- Check out mitmince.com and @mitmince on Instagram to learn more about our events, recipes, team, and general thoughts on food. (PS: Even we’re a little confused about the stylization of our club name. But we love the feel of 'mince.' It’s an action that often marks the start of a recipe, and by that understanding, 'mince' is an act of creation.) back to text ↑

- I don’t include the previous details to perpetuate a ridiculous conclusion that because someone is well-educated at an institution like MIT, their goal must be to climb the ranks at even more elite institutions. I include it to illustrate a freedom of choice and diversity of opportunity that few people have access to, making his decision all the more thoughtful. back to text ↑