How did MIT’s GIRs come to be? by Chris Peterson SM '13

the Tech has some answers. Plus, the SATs from 1918, and a mascot on a big cow

First, just to allay the inevitable questions in the comments: we’re still heads-down reading applications and meeting in committee. No final decisions for Early Action have been made. We’ll release the decision date once we know it; we’ll likely make that announcement on the blogs late next week, so stay tuned. I’m just popping my tired head up for a moment to post something I’ve had in the backlog for awhile.

Last year, I was involved with a class devoted to (re)designing the first-year academic experience at MIT. The initiative, which is ongoing, has been considering many aspects of the early MIT education, including not only introductory coursework but advising, major exploration, and so on. However, there has been a special focus on the substance and purpose of the General Institute Requirements (GIRs) that conventionally (but not necessarily) compose the majority of the academic coursework taken in a student’s first year.

Earlier in the fall, the Tech published a fascinating history of the GIRs. It’s one of the ways I learned that MIT was designed for democracy, but more fundamentally, it traces the development of the MIT common curriculum as it has changed through time in the service of the principles articulated by MIT’s founding President William Barton Rogers:

“We believe [an education should be] founded on a thorough knowledge of scientific laws and principles, and which unites with habits of close observation and exact reasoning…and we read in the history of social progress ample proofs that the abstract studies and researches of the philosopher are often the most beneficent sources of practical discovery and improvement.”

– William Barton Rogers, Objects and Plan of an Institute of Technology (1860)

For example, did you know that:

- for its first few decades, MIT students were required to learn not only math and science, but French and German, but also courses in military tactics and strategy?

- the swim test was instituted in 1948 upon the recommendation of an athletics committee and not, as every tour guide everywhere ever has lied to you, because a wealthy alum’s child drowned on the Titanic?

- the creation of the MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (SHASS), and the HASS electives required by the GIRs, were recommended by a committee chaired by Warren K. Lewis, a chemical engineer who had been involved with the Manhattan Project and thought it imperative that scientists and engineers be trained in social and humanistic concerns for the survival of humanity?

Read the full article! It’s a great history of what MIT has found important in education and how it has tried to build that into a lasting curriculum.

On another historical note, I know that some of you are taking the SATs today. I remember how much it sucked to sit in a room for several hours on a Saturday with a #2 pencil and a lot of anxiety. My heart goes out to you.

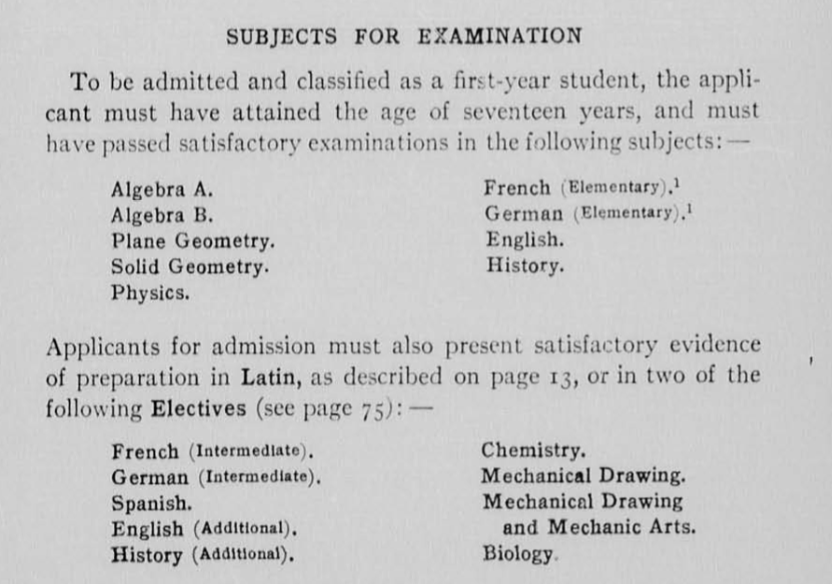

But — it could, somehow, be worse! A hundred years ago, MIT didn’t require three tests, it required 11, and it didn’t take three hours to complete them, it took three days.

I guess my message is…standardized tests aren’t fun, but at least they’re not as bad as they used to be? On that uplifting note, I’m going to get back to reading, and hope you all have a great last month of 2018. In conclusion, here is the blessed image of Gritty riding The Cow Who Is Too Big To Be Killed.