“Picture yourself as a stereotypical male” by Michelle G. '18

and other ways to improve your test scores

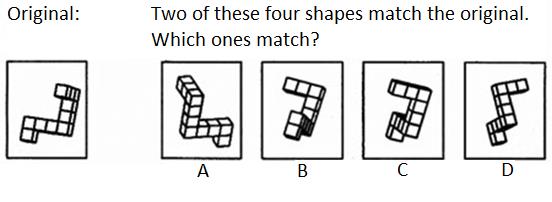

There is empirical evidence to support the idea that males have a higher capacity for spatial reasoning than females. A large-scale 1995 meta-analysis found that on average, men outperform women in a cluster of tests related to spatial ability by nearly a full standard deviation, and in attempt to explain this, researchers have hypothesized about the impact of testosterone and differences in brain wiring in capacity for spatial thought. It has also been suggested that this difference in performance is in some way related to differences in math ability, given that college-bound females who perform well on SAT math also perform correspondingly well in mental rotation exercises. “Mental rotation” here refers to the act of visualizing rotations of two- and three-dimensional shapes in one’s mind, and tests of this ability have widely been used as one measure of spatial intelligence.

Example of a mental rotation test.

I’m guessing that you’re familiar with common notions that men are spatial and logical thinkers, while females are more verbally proficient. A man being tested for spatial ability might assume that he’s going to have an easier time than a woman of otherwise equal intelligence, his conclusion based not on sexism but on objective science. And statistically speaking, he’s right.

It is true that men score higher on spatial reasoning tests, though you might have caught on that there’s a little bit more to this picture (why would a female MIT student publicize stereotypes that actively work against her?). If you’re now wondering whether I’m about to throw some kind of feminist rant at you, I’ll give you a “well, sort of,” because calling out factual misconception is just as important as promoting feminist ideals here, and because I think those two go hand in hand anyway. I’ll largely put the romance of egalitarianism aside, though, to talk about empiricism.

If you’ve ever done any kind of research, you’ll know that while correlation doesn’t imply causation, a controlled experiment can. As in, one can reasonably conclude that women score lower on certain types of tests as a result of them being women, and that some aspect of their womanhood has brought on this result. The question of interest, then, becomes “which aspect” – a question which has evoked a number of hypotheses that incorporate innate or nature-driven difference. Is testosterone key? Are women’s brains wired differently in a way that impair their visualization ability, and if so, is this difference breadboarded by biology or by social environment (in perhaps the same way that the taxi driver brain physically adapts to enhance spatial mapping)? And could this potentially have something to do with the separation of labor of our hunter-gatherer predecessors?

I think it’s important to acknowledge the very rightful discomfort that arises when scientific studies attempt to trace such differences to biologically determined origins. Yet, across decades of research, no biological cause has actually been identified as a suitable explanation for the spatial reasoning discrepancy. Studies regarding testosterone and mental rotation, for example, found inconsistent or absent effects across cultures, prompting inquiries into “differing cultural values” to account for the results. And gaps between men’s and women’s scores on some spatially-geared tests have significantly shrunk in the past few decades, which is interesting because noticeable evolutionary or nature-based development might take thousands of decades to take effect. (“Nurture”-based conditions are of course rapidly changing.) Still though, the gap has lingered, and a satisfying and empirically-supported explanation as to “what gives” was not achieved until 2008, when researchers eliminated the performance gap under a single simple condition.

In a now-famous study, psychologists at the University of Berlin falsely told participants that they had been selected to participate in a series of tests “to measure the ability to put oneself in someone else’s position” – a fabrication devised to avoid confounding factors in their real study on gender identity priming. They prepared a text describing a day in the life of a “stereotypical woman” who takes care of her family, works part time, and is insightful, helpful, and agreeable. They also prepared an equivalently-structured text outlining the activities of a stereotypical manly man who is tough, risk-taking, and does weight training after work. Subjects were randomly given one of the two texts, and then asked: “If you were the person described in the text, which adjectives would you use to describe yourself?”

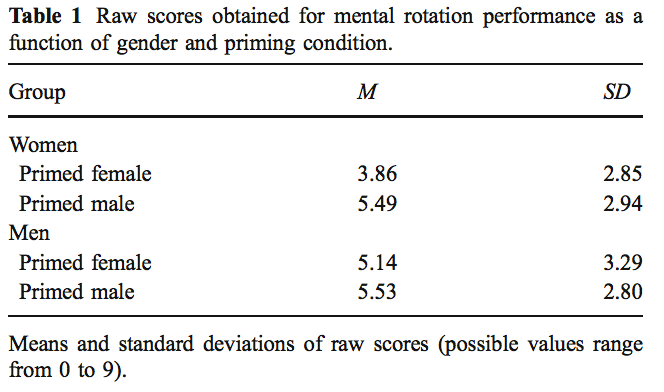

Soon after participants described themselves with either the male- or female-associated traits, they were asked to take a mental rotation test presented as independent of the first part of the study, supposedly to measure their personal spatial aptitude. On this mental rotation test, women who were “primed” with the female identity scored an average of 3.86 on the exercise, compared to the female-primed males’ average of 5.14. Okay, expected. But then when primed with the male text, women scored an average of 5.49, while men scored 5.53… wait a second, what?

As it turns out, there is zero statistically significant gender difference in mental rotation ability after test-takers are asked to imagine themselves as stereotypical men for a few minutes. None. An entire standard deviation of female underperformance is negated on this condition, just as a man’s performance is slightly hindered if he instead imagines himself as a woman. (well then.) Although this study is of course not a logically definitive answer to all things “nature versus nurture,” it does add a tremendous structural asset to the growing mountain of evidence that “natural” ability differences are confounded by identity and subconscious self-stereotyping. Demographic expectations may be subtle or overt, but they are omnipresent, and they are likely much more powerful than most of us have ever considered.

A Good Night’s Sleep, A Hearty Breakfast, and Being White

I’ve been taking standardized tests since I was nine years old. Back in elementary and middle school it meant this kind of magical week where homework wasn’t a thing and we had half the school day to do whatever we wanted, but come high school it was more this ugly ominous mutant mess of big words and big blue practice books. Hallway whispers insisted that “X person isn’t that ‘good,’ they only got X score,” and “I’m never going to college, I’m so stupid.” It was named the Scholastic Aptitude Test, after all.

Our guidance counselors always liked to talk about how we should take care to get eight hours of sleep and a nutritious breakfast on our testing days. Test prep was obviously first and foremost, but after that, there were a number of easily–Googleable studies that correlated sleep with test performance and nutrition with test performance. It was sort of like this ritual mantra among counselors and parents: study, sleep, eggs for breakfast. If you had the trifecta covered, your score would be up to some combination of fate and the will of the Greek gods and there was nothing much else of concern.

Some time last month I was browsing the Internet and happened upon a number of papers that really disturbed me. This reaction, I would say, was both due to their content and to the fact that I was priorly ignorant of their actually enormous implications for anyone who regularly test-takes. I found it 1) absurd that this isn’t common knowledge, and 2) upsetting that educators spread these cute little test tips while ignoring factors that affect students on potentially magnitudes greater. How about “Zeus is a fucking racist, kids,” or else “stereotype threat exists.”

You may be familiar with the concept of stereotype threat. The term refers to a theorized mechanism by which people underperform (on tests, competitions, etc.) in response to awareness of stereotypes about their demographic group. It’s related to a largely subconscious apprehension about confirming the given negative stereotype, which hinders cognition, impairs concentration, and under some conditions reduces preparation or effort. This concept was conceived in a breakthrough study in 1995 entitled “The Effects of Stereotype Threat on the Standardized Test Performance of College Students.” Its introduction explains: “Whenever African American students perform an explicitly scholastic or intellectual task, they face the threat of confirming or being judged by negative societal stereotypes about their group’s intellectual ability and competence… and the self-threat it causes – through a variety of mechanisms – may interfere with the intellectual functioning of these students, particularly during standardized tests.” The study analyzed the effect on black participants, although similar effects surely apply to Hispanic and Native American people and any other group with academic prejudices working against them.

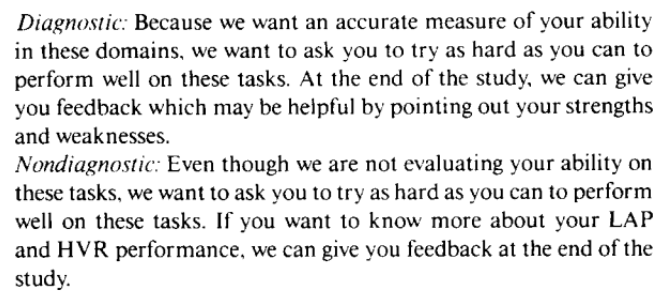

“When participants arrived at the laboratory,” states the paper, “the experimenter (a White man) explained that for the next 30 minutes they would work on a set of verbal problems in a format identical to the SAT exam.” Half of the participants were told that their performance on the test would be diagnostic of their verbal reasoning abilities, or in their words, “a genuine test of [their] verbal abilities and limitations” due to “various personal factors involved in performance.” This was an engineered induction of stereotype threat, under which the test takers were given the impression that their score on the test was associated with their personal academic aptitude. In contrast, the researcher’s explanation in the non-diagnostic condition made no reference to innate ability and instead implied that a given participant’s score was associated with the kinds of problems they’ve been exposed to in the past, along with test-induced “psychological factors.”

I want to point out how closely test scores are associated with intelligence in our common thinking. Obviously, we reason, one scores an A on a Real Analysis test because they’re really smart. Man, those smart kids at MIT are faced with some of the most brutal exams in the country. But I got an easy question wrong on my 8.02 midterm, so I must be pretty stupid – or at least not destined for Physics. Such words and notions are thrown around so casually.

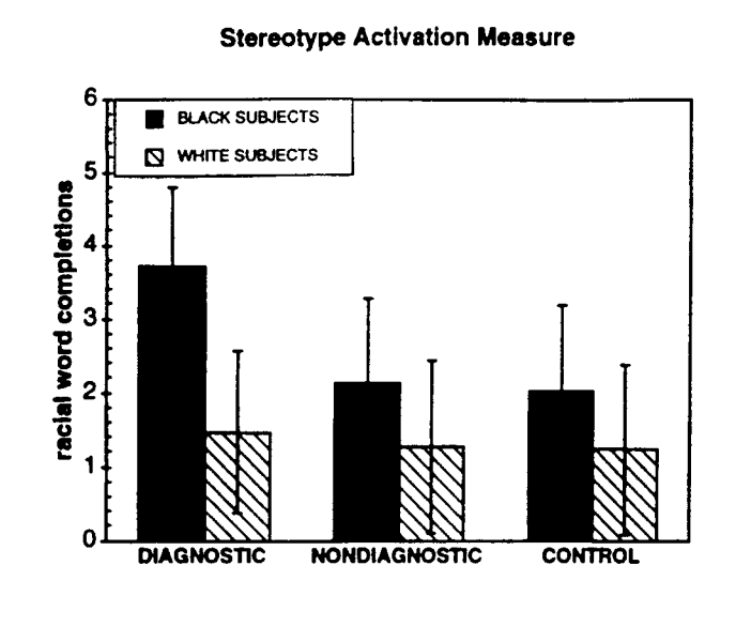

With that said, I also want to show you exactly what happens when a test is perceived to be “diagnostic” of a negatively stereotyped person’s intelligence:

(hah.. ha ha…ha…excuse me for a second while I unleash a blood curdling scream in the general direction of anyone who has ever complained about affirmative action.)

Black students under the “score is based on your personal intellect” condition performed significantly worse than whites, while the black participants who were given the alternate context performed with zero significant difference. Stereotype threat impaired both the rate and accuracy of their work, as they spent on average 94 seconds per question in the diagnostic condition versus 71 seconds without it. Interestingly, no differences were found between the conditions in self-reported anxiety; the paper notes that “these measures may have been insensitive, or too delayed.”

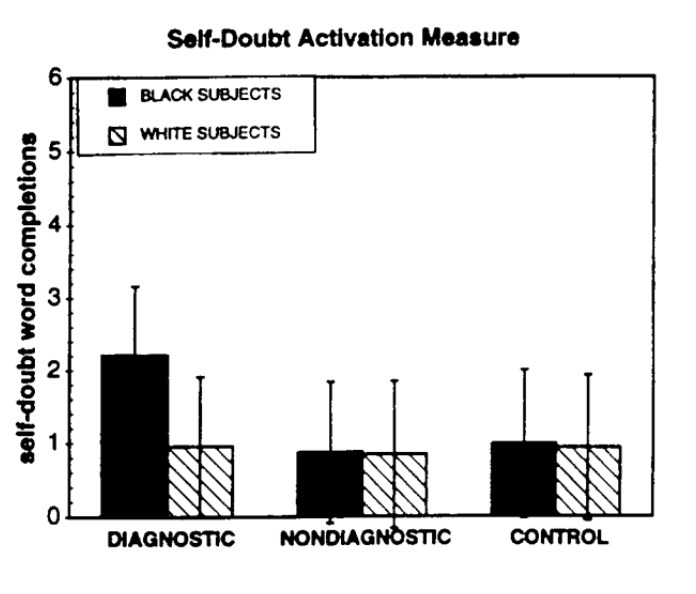

In another part of this study, sixty-eight Stanford undergraduates were told they were participating in a study on Lexical Access Processing, or “the visual recognition and processing of words.” The task was made up of 80 word fragments with missing letters, which – as the experimenters intended – could be completed in a number of different ways. For example, “ _ _ _ T E” could be anything from “flute” to “white” and “D U _ _” could be “dust” or “duty” or “dumb” and so forth. “Stereotype Activation” would be defined as the completion of words relating to race, and the “Self-Doubt Activation Measure” would measure the completion of words related to anxiety over failure. The diagnostic versus non-diagnostic conditions were defined similarly to the previous portion:

The results were really no less upsetting.

According to this study, black undergraduates at Stanford (i.e. some of the most academically accomplished students in the country) are significantly more likely to be thinking “D U M B” and “R A C E” when their ability is reflected by their score. And as determined by the previous portion, these anxieties – whether the students report having them overtly or not – can have very real consequences for their test performance and their resulting academic achievement.

“My Entire Gender is Counting on Me:” More Tales of Literal Impaired Cognition

If you’re a female or demographic minority in STEM, the cute comic above might evoke some not-so-cute memories of a familiar and horrifying scenario in which you feel judged in a class of an out-group majority. Maybe it won’t surprise you to know that a girl’s math performance is empirically shown to decrease in proportion to the number of male test-takers around her, or that conscious reminders of gender differences will significantly decrease females’ math test scores.

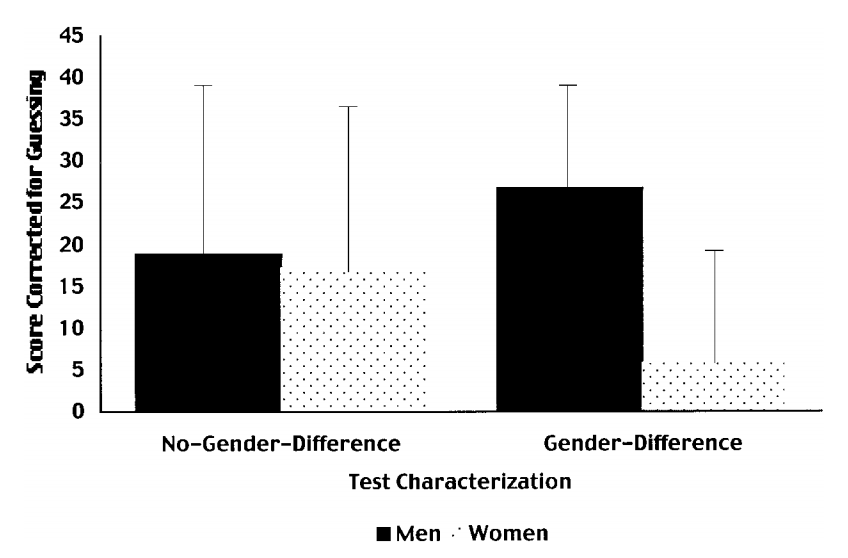

This week’s episode on “Graphs That Will Make You Want To Cry,” featuring a math test composed of “challenge” problems in another famous stereotype threat study.

There have been hundreds of equally alarming studies regarding stereotype threat and of similar identity-related conditions that impair performance. I don’t think we have time to recount every one in detail, but I’ll leave you with some more interesting findings. Regarding women in math: research at Indiana University found that females’ performance decreases significantly after simply watching a video showing “dominant” male behavior, and at Harvard they found that Asian-American women perform better or worse on math assessments depending on which identity is highlighted to them. A 2005 study showed that girls score much lower than boys on an identical test when it was described as a “math test,” but slightly (though non-significantly) better than them when it’s a “problem solving” test. Another study suggested that female AP Calculus test-takers would benefit if the demographic bubble-filling were postponed until after the exam.

Similar findings have been shown regarding racial identities: for example, asking black students to indicate their race before a test both significantly increases their anxiety and lowers their test scores. Black students’ performance under a “diagnostic” condition is improved when the test administrator is black as opposed to white (that 2.9% black MIT faculty tho) and black participants taking what was actually an IQ test scored better when the same questions were presented as a test of “hand-eye coordination.” Unsurprisingly, the same stereotype threat effects that were initially found for black test-takers were also found to apply to Latinos and students of low socioeconomic status.

More recently, neuroscientists have begun to examine the effects of this condition under an fMRI. Under a control (non-stereotype threat) condition, Dartmouth undergrads engaging in mathematical problem-solving showed activation in the typical brain regions associated with problem solving. In the stereotype threat condition they were reminded that ‘‘research has shown gender differences in math ability and performance,” a reminder that I know I would personally take to mean “try harder.” However, regardless of this expected greater effort, participants showed no evidence of heightened activation in problem-solving areas and instead showed activation in the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, which is implicated in the processing of not “trying harder” but rather of negative thoughts and emotions. In other studies, inducing stereotype threat has been shown to temporarily reduce working memory capacity, which is one of the strongest correlates with general intelligence… and as an interesting self-referential side note, is also related to mental rotation ability.

The negative impacts of this cognitive burden aren’t limited to test-taking, though: thoughts of stereotypes degrade women’s performance in activities from chess to negotiation to driving. Nor does it apply only to women and people of color; the same mechanism is thought to cause men to find social sensitivity more difficult, psychology majors to test worse than science majors, and drug users to score worse on a memory task when faced with this expectation.

Michelle I’m Pretty Sure You’re Just Reminding Everyone of Stereotypes with this Post…

You guys wanna know a few things? I’m a girl, and I’m white. My favorite movie is James and the Giant Peach. I am somewhat soft-spoken, though I like to sing really loudly in my room. I can be introspective to the point of self-torture and procrastinate to the point of well, future-self torture. I’m studying Course 14.

I’m generally good at math, but I tend to think the humanities are more fun. I was always one of the best writers in my English classes and I’ve done professional graphic design work which I’m proud of. And I know it sounds annoying to say, but I do think that I’m smart.

Sometimes I go into exams thinking about like.. feminism and disproving stereotypes. I know now that that’s bad, but I’m 99% sure that other girls do it too – because how can we not? – especially in situations where we might feel like we’re representing all of womankind. I really can’t even begin to imagine what that pressure might feel like if I didn’t have white skin, although studies like Steele and Aronson’s give me a hint that it’s, uh, not great.

There is something of a solution to all of this: one that’s a bit more complicated than to “stop being affected by stereotypes,” a bit less fun than “deporting all the meninists” and of course in addition to a long-term ideal of say “destroying the culturally-ingrained white supremacist patriarchy.” See, we know that highlighting identities associated with impaired performance will cause impaired performance, but as a counter to this, research also confirms that thinking about our complex, intelligent, talented, individual human selves before the given tests will partially or completely dissolve this impairment. So theoretically we can sort of “engineer” out any test impairments with a combination of these techniques and perform with a lot more cognitive clarity than an extra scrambled egg for breakfast could give us. (Though still not as effective as the “destroying the hegemony” thing. Which by the way, requires the participation of everyone, and not just those it impairs.)

I am a multi-faceted person. I’m an MIT student and an East Campus resident. I’m terrible at basketball and I always win at Mario Party. I like to give encouraging life advice to my sisters. I am a girl, which I think is pretty cool. I get anxious sometimes but I know rationally that a lot of this is due to outside pressures working against me, and not a result of my true aptitude. I am a smart person. I am a capable person. I am a capable person.

And yes, I should mention that in addition to changing the way we think of our exams and ourselves, simply learning about how stereotypes unfairly harm performance does ameliorate a portion of its effects. A group of researchers told female math test takers: “It’s important to keep in mind that if you are feeling anxious while taking this test, this anxiety could be the result of these negative stereotypes that are widely known in society and have nothing to do with your actual ability to do well on the test.” The girls’ scores significantly improved, an effect which I would assume holds for people of color and for anyone else whose brain is taught to expect less from itself by a culture that wants this to be so. I think it’s awful and unfortunate that we live in a society that can impair us based on the basic properties of our human existence; a world that tries to undermine excellence by spreading burdensome fears. Yet as diverse, talented, and intelligent individuals, I’d hope we’re smarter than to allow it.