Underwater Dreams (from a distance) by Natasha B. '16

A reflection on immigration, student activism, and civic engagement at MIT.

A month and a half ago, a 450-seat lecture hall at MIT filled with people, and those peopled filled with eagerness, then silence, then questions, then hope. The event was the showing of Underwater Dreams, a documentary about an Arizona high school robotics team of undocumented Mexican immigrants. “Ten years ago, they beat MIT,” reads a headline on AZ Central.com. “Today, it’s complicated.” The film screening was followed by a discussion panel. Sofia Campos (MCP 2015), Jose G. (Course 16, Class of 2017), Renata Teodoro (of UMass Boston and United We Dream), and Junot Díaz (author, Pulitzer-prizewinning MacArthur Genius, MIT professor, and Dominican immigrant) took questions from the audience. They spoke movingly, optimistically, and devastatingly. Yuliya blogged about it. I scrawled words on the flyer I’d taken at the door, wanting to remember every sentence I heard, every piece of the story.

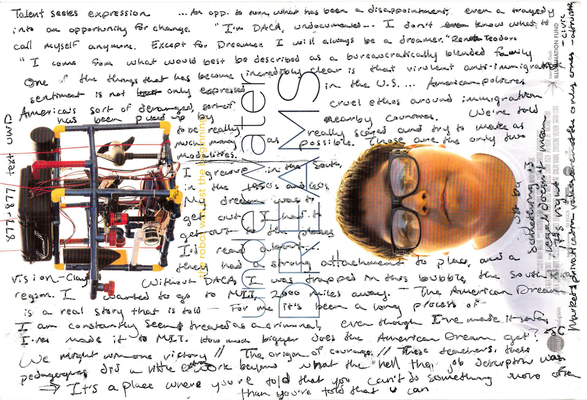

my notes on the flyer… brochure? pamphlet? card? whatever you call it, it was sturdy and well-designed

The next day, I approached a friend. Ruben P. ’18 had stood up before the panel, and along with several other members of DreaMIT, come out as an undocumented immigrant. He is laid-back, friendly, with a subtle sense of humor. When I asked him what he’d like to say to students in his situation, undocumented students thinking of applying to MIT, his response was quick.

“Do it,” he said. “You never know what’s gonna happen.”

He told me his story, or part of it, at least. No one’s journey to MIT is typical. His wasn’t. This is what he told me:

“We all took different paths, my brothers and sisters,” Ruben said. “My youngest brother was born here. Everything’s gonna be different for him, because he has papers. I’m glad he doesn’t have to struggle like we did—once you’ve been through that, you don’t want anyone else to go through it—but I hope he learns to fight as hard as we did.

If you have the money, you have the status, you have so many opportunities. You can hand them off to your children. I’m a first generation everything. First generation middle school, high school, college. People asked me, I wondered, why am I working so hard if there’s no guarantee that I’m gonna make it? You never knew if you would be allowed to go to college [because of your undocumented status]. Some teachers didn’t think I should even try.

Fuck your shit, was my response. I’m doing this. I’m doing it better than anyone else in the school.”

He did, and he’s here.

DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) granted Ruben a two-year work permit and exemption from deportation. “It’s a temporary thing,” he said. “You don’t know what you’re gonna do if this falls through.” And DACA does not offer protection to everyone. He echoed Sofia’s words from the night before: “There are 12 million undocumented people in this country, and my parents are a part of that story just as much as I am…. Even though I have deferred action, which grants us safety from deportation and legal work permits, I still live in fear that my parents will be deported any day. I still live in fear that when my DACA expires… what’s gonna happen then?”

Things have changed. These conversations took place before Obama’s executive action on immigration. Of the millions of undocumented people living in the United States, many more are safe now than were before. DACA has been expanded and the age cutoff for applying has been removed. The parents of some green card holders and U.S. citizens will be protected, and “cases involving immigrants and families with no criminal history” will become lower priorities relative to cases involving immigrants with serious criminal records. These reforms have come late and hard, but they have come—thanks to people like Sofia Campos and Renata Teodoro. They are DREAMers, young, undocumented activists and organizers building a movement around their own histories. They are not finished, nor are they narrow in focus. If the panel that night had a theme, it was hope sustained by action, collective and individual. Sofia spoke on unity and intersectionality. Renata spoke on courage and perseverance. Jose gave heart to people facing the obstacles he has overcome. Junot told us the importance of civic engagement. And a young man in the audience, Austin Thompson, asked a question that struck the core of the conversation.

“My name is Austin Thompson,” he began, “and I’m extraordinarily happy to be in here, considering I was on the waitlist.” He smiled, and the room—full to capacity—murmured laughingly.

“I am African-American,” he continued, “and growing up I knew that my ancestors didn’t choose to come here, that they were brought here, and I heard folks on the panel talk about how they envisioned America, what it could look like. I grew up envisioning, where else could I go outside of America. Walking down the street, dribbling a basketball, a neighbor called the police on me. The police put me in handcuffs at twelve years old, put me in the back of a cop car not believing that I lived there, and I had to call my parents to prove it. So the sense of not belonging I’ve understood. There’s a cognitive dissonance when the ideal place to escape to is where I live and where I’m experiencing the unbelonging. And that’s my fascination– I’ve always been attracted to the undocumented movement because I think what it does is it opens up a deeper question about who belongs, and what does ‘We the People’ really mean, and how do you all conceive of a transformative movement that includes people of all different ethnicities, backgrounds, identities, but goes beyond citizenship to the existential question of who belongs, and who matters in America.”

He asked this question before November 24, before last Wednesday. Before the grand jury decided not to indict Darren Wilson for the shooting of Michael Brown, before the announcement that there would be no charges against Daniel Pantaleo for killing Eric Garner. Before the most recent legal flourishes confirming the continuation of our country’s violent, racist history. But the protests had begun, and the grief and resolve had begun to spread, and the audience, this night, was receptive. Sofia’s answer was spot on. I don’t want to string any more of the panelists words together loosely, interrupted by my own. Below are some of the notes I took—powerful quotes from the panelists, starting with Sofia’s response to Austin.

Sofia Campos:

“Reaching for our dreams of our transformational kind of process to transform our society, transform our fear into love, I think is a very important goal, and something that can’t be done alone, but can only be done together. And something that isn’t only going to impact this country, but is going to impact the world. I’m learning about China right now and Chinese immigration, and I’m seeing just how much impact U.S. policies have across the globe. The fact that we have the world record for deportations in this country—over 2 million, just under the current administration—speaks volumes as to how we see humanity and how we see how the world should be in the future. We don’t only have the world record of deportations, we also have the world record of incarcerations, over 2 million also. And that’s a black and Latino issue. Unfortunately, right now, we have for-profit prisons that make money off of undocumented people, immigrants, black people, brown people. Literally, you can arrest somebody, hold them in a detention center or a jail for an inordinate amount of time, and corporations, companies are making money off of that. How did we let it get to that point? It’s not just the corporations doing that. It’s all of us, letting it get there. And so for me, organizing, building relationships, not just learning about my identity but learning how all these things are connected has opened up my mind and opened up my heart in ways that I never imagined possible. And now, I don’t want to go to college to make money, that’s not my intent at MIT. That might have been my intent when I tried to go to UCLA, because that’s how they teach you to think about college oftentimes. You go to college to make good money, and get a good job which means you make more money. But through the movement, through organizing like I said, I learned discipline, I learned strategy, and I also learned people power, and something bigger and better than money. And so my purpose for being here at MIT was to brainstorm ideas for how to reach that kind of transformation and that kind of society. I’ve learned that it’s very complex. I hope there are a lot more people who want to reach for that vision with me, because there’s no way a few people can do it alone.“

“I’m here because I’m honoring the sacrifices that my family has made. …I graduate in May year with my Master’s in Urban Planning, and I have become empowered through the immigrant youth movement, I have able to find my own voice and find my power, find my story and be able to tell it in a strong and powerful way. Because of my undocumented status and because of the reality and truth that my peers showed me rather than what the media showed me. My parents chose to keep our undocumented status a secret because of what society told us undocumented meant, illegal meant, alien meant. All of that shame, all of that fear, all of that stigma, is created by a society and created by a system… that is crazy, and that is illogical, and that is inhumane, also. Our group DreaMIT and our immigrant youth movement shows us otherwise, and proves to us—in mind and education, but also in heart and in storytelling—that there is a better way, and that we can work to create that change. We won deferred action through our immigrant youth organizing. It was a total national undocumented youth-led movement that won deferred action, and it’s a small step in something much greater that we’re trying to achieve. It’s not a complete tragedy. It actually has a lot of heart in it, and a lot of love, and a lot of hope.”

Philip Clay (former chancellor of MIT, professor of city planning, and the moderator of the panel):

“What jumped in my mind was the idea that talent seeks expression. All of the individuals from Carl Hayden High that we got to see…all of them were seeking to have, in a very joyous and a very active way, an expression of their talent. We have to take responsibility for whether that talented is fully realized, whether that talent is allowed to grow, and of course we saw that it was not. We have a very good opportunity to turn what has been a disappointment and even a tragedy in terms of the lack of engagement with expanding opportunity into something different.

And Junot Diaz, who drove the point home:

“An extraordinary part of being alive at this time is that our youth have taken up with so much of our political and religious and academic leadership, have advocated this sort of ethical, moral compass for our nation. It’s been an extraordinary thing to witness and to be a part of. We live in a country where we’re basically told to be really scared and to try to make as much money as possible, and those are about the only two modalities people should live in, and yet we have this group of young undocumented activists and community workers who have really provided an alternate model, for not only how to be a civic-minded person, how to be an American, but also simply how to live, and how to live ethically, and how to live in a way that is very human and humane, and that has been incredibly inspiring.”

We ask ourselves these questions, trying to figure out how to live. We go on living in the meantime, working, tending to the nitty gritty, keeping ourselves afloat, but we must return to these questions. Tomorrow, we may wear black. Maybe we’ll get distracted or overwhelmed or tired. Maybe we’ll hear a new story and remember it, find new hope and latch on to it. Narratives are helpful because they contain progress; stories are powerful when they contain hope.

That’s all I’m writing tonight.