An unexpected discovery, from a few centuries ago by Anelise N. '19

It takes more than four years to get to know a place

This is my fourth year in Cambridge. But earlier this week I learned how little I still know about where I live.

Last weekend, I went on a grocery run. It was wine and cheese night in my suite, so I was preparing an appetizer of brie sprinkled in candied walnuts, wrapped in puff pastry, and baked (here’s the recipe, in case your mouth just started watering!). To my horror, Trader Joe’s had neither puff pasty nor brie, which didn’t bode well for my dish.

Well it turns out there’s a big Whole Foods Market literally a 5 minute walk from the Trader Joe’s I frequent that I had no idea about until last week. I picked up my cheese and pastry, sheepishly thinking about all the other times I’d left Trader Joe’s in disappointment, and headed back to MacGregor.

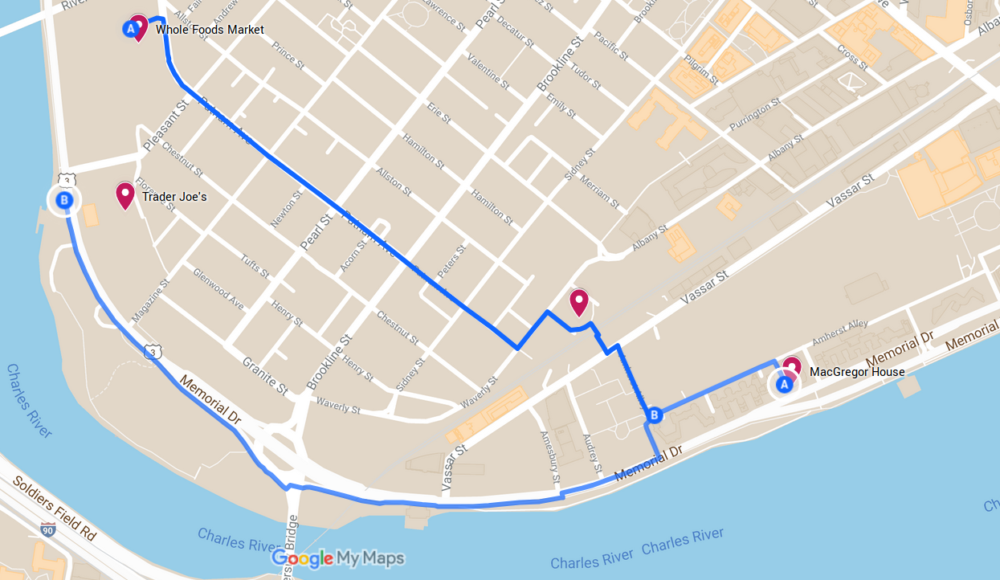

Usually when I go to the market I take the river route along Memorial Drive. But because I ended up at a new store, I took a different street back to my dorm.

Usually when I go to Trader Joe’s, I walk along Mem Drive, but I cut inland this time.

On my way back, I stumbled across a park.

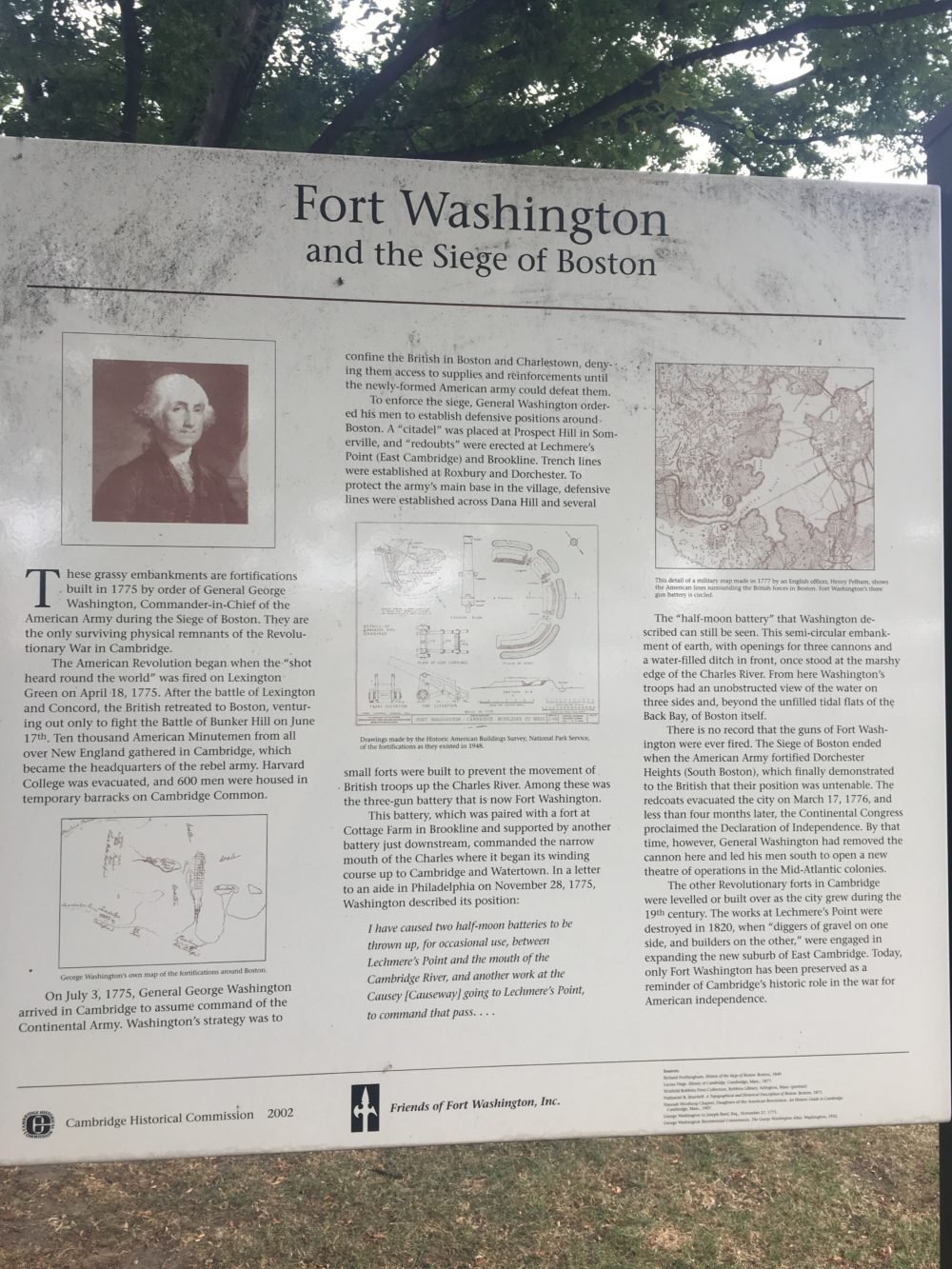

In the park, I found a sign:

The sign explains that the miniature hills ringing the park are actually embankments built in 1775 at the command of none other than George Washington. After Lexington and Concord, the pair of battles that started the American Revolution, the British soldiers fell back to Boston–and the rebels, including ten thousand Minutemen from all over New England, set up camp in Cambridge.

At the time Cambridge was nothing more than a “village” of around 1500 people, but for a short while it served as the military base of the army of a country that didn’t even exist yet. Harvard was evacuated and barracks were set up in Cambridge common. Washington ordered that defensive positions be established throughout the greater Boston area, in Sommerville, East Cambridge, Brookline, Dorchester, and Dana Hill. This small three-gun fort was one of several established on the banks of the Charles River to restrict British passage on the water. The semicircular battery would have given the American troops an unobstructed vantage point over the water on three sides.

The guns likely never saw action. The British were driven out of the city in March 1776, ending the Siege of Boston, shifting the war to a different theater, and paving the way for the signing of the Declaration of Independence months later. This fort–now a park filled with fluffy dogs–is the last preserved monument to Cambridge’s role in this very early stage of the Revolutionary War.

This is why I love Boston–it’s so full of history that you can basically trip over fascinating monuments without realizing it.

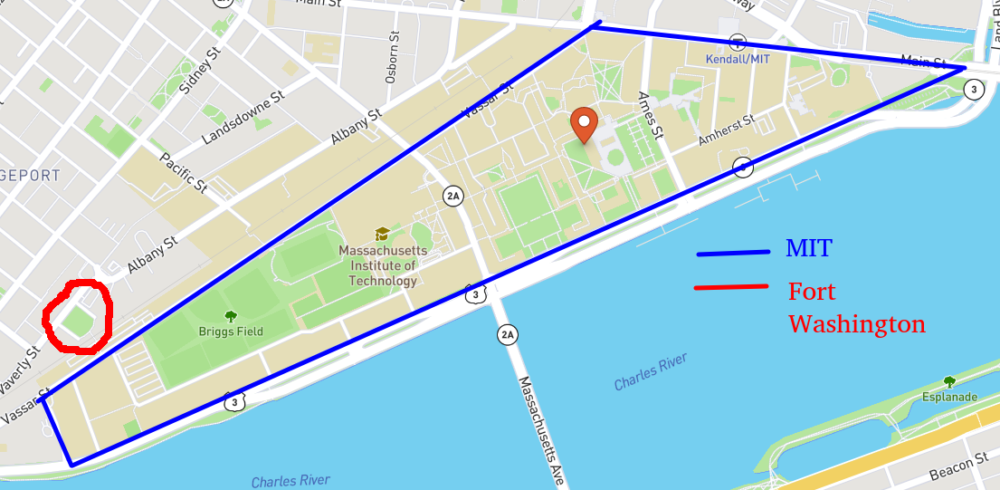

Now you might have noticed that the park is not actually on the banks of the Charles River. Instead, it’s within spitting distance of Simmons, the giant undergrad dorm that looks like a sponge.

That’s because MIT, like a lot of Cambridge and almost all of Back Bay, was built on artificially filled land. Not only did the university not exist when America was declaring its independence–neither did the land it stood on.

Originally, Boston proper was a tiny little plot of land, a peninsula tethered to the mainland with one tenuous spar of rock. During the 19th century, Boston leveled most of its hills in order to fill in vast swaths of land in South Boston and Back Bay. National Geographic has a fascinating article detailing the history of the city’s transformation; you should really check it out.

Now that I know that a lot of the ground I walk on day-to-day is man-made, there are some things that make a lot more sense. For instance, when Paul Revere stood watch in the tower of the Old North Church, he promised to sign “one if by land, two if by sea” to indicate from whence the British were coming. This was actually a fairly comprehensive code because at the time there was literally only one land route into Boston. My dad used to make fun of Harvard for not grabbing the prime real estate on the Charles River and instead leaving the waterfront to MIT; but when Harvard was founded MIT’s campus was a big plot of marsh. I’ve actually been commuting back and forth to Harvard lately because I’m taking a class there this semester, and apparently Dana Hill, one of the reinforcement points mentioned on the sign, is smack dab in the middle of my commute. Dana Hill is not tall; I know because I have to bike over it twice a week. Or maybe it was just leveled to fill in the ground where my dorm is now.

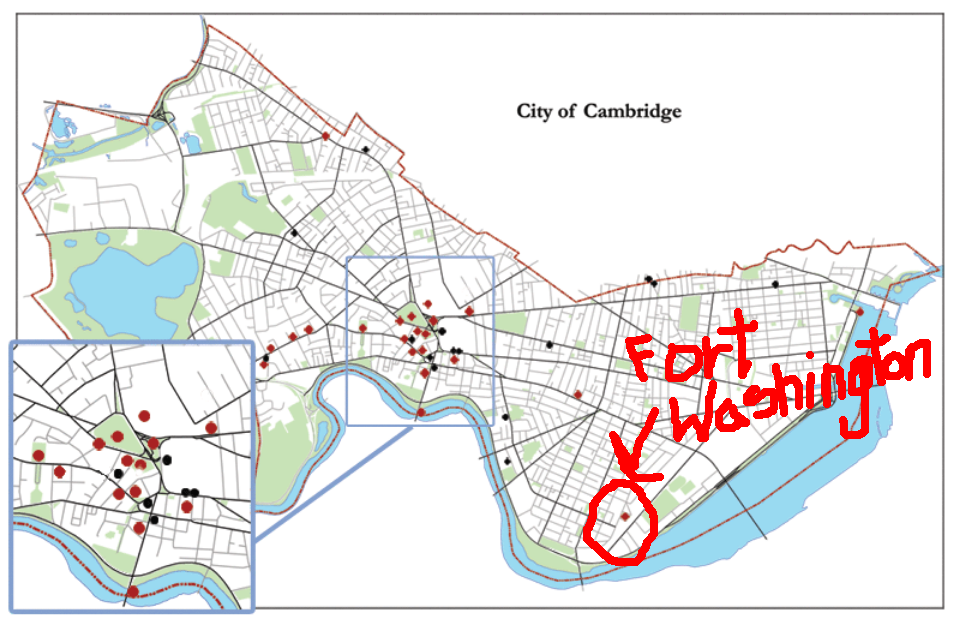

The City of Cambridge actually has a map showing where all the cool Cambridge historical sites are. As is to be expected, they are clustered around Harvard, where land existed back then. Now that I’m heading over there more often, I should be able to check some of them out.

There’s Fort Washington waaaaaaay over there in the corner…where the water used to be

My day started out with a typical walk to the grocery store, and instead I stumbled across a fascinating piece of history that is literally two blocks away from my dorm that I had never found before. I’m honestly amazed and embarrassed that I didn’t know about it.

I guess this should be a lesson to myself to not let myself get buried so far in my classwork that I don’t take the opportunity to explore what’s around me. It’s really easy to get trapped in the “MIT bubble”…but sometimes it’s important to make sure you get off the refilled land.