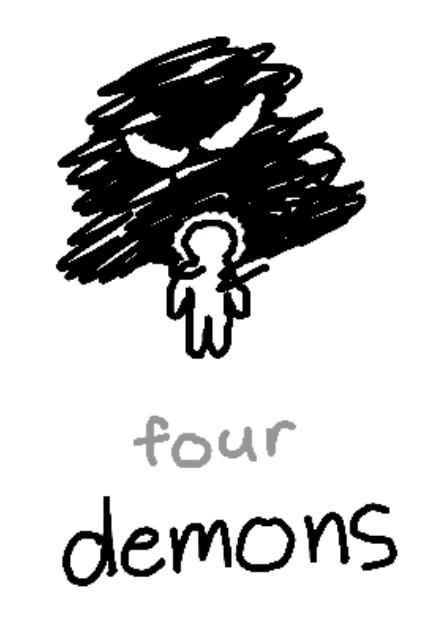

demons by CJ Q. '23

on depression

Content warning: depression, emotional abuse, suicide.

In the late 1800s Galton described aphantasia, the inability to create mental images in one’s mind. It turns out the majority of people, when asked to visualize something, kind of see a picture in their head vividly, which can feel like looking at the actual thing. And like many things, different people vary in how vivid their visual imaginations are, with some seeing it very clearly, others seeing something blurry, or only outlines. But there are around three percent of people who are completely unable to visualize things, or who have aphantasia.

I didn’t realize I had aphantasia until maybe four or five years ago, which was roughly the time when aphantasia became a popular concept. I’d just always assumed that when people talked about seeing things with their mind’s eye, they meant it metaphorically, not as if they could actually see it, not to the point where it could be so vivid as to touch it.

When I “visualize” a banana, well, I know what it looks like. I know what its color is. I know its shape. I can draw a banana. In all respects, I can act like someone who is actually seeing a banana. But it’s not at all similar to looking at a banana; it’s just bringing to mind what a banana looks like. I have never visualized a banana, and I probably never will.

I made the connection between this and asexuality a few months ago. I’ve known for a while now that I was asexual, in the sense that I’ve shared a lot of experiences that asexual people describe. For example, not really wanting to have sex, aside from just intellectual curiosity of what it’d feel like. Or not understanding how sex felt different than masturbation. And these weren’t, apparently, experiences that non-asexual people had.

There was always that doubt, though. Could I really be asexual if I enjoy cuddling or kissing? It wasn’t until I read descriptions of what sexual attraction felt like that I became sure I was asexual. It turns out that people aren’t exaggerating or speaking metaphorically when they say that sexual attraction can be an intense, visceral feeling, because it can be, and that is how some people feel it. It just is that way to some people, and it’s not that way to me.

There’s a Quora answer that describes anosmia in interesting detail. For fourteen years, the author didn’t realize they had anosmia, up until they were asked to describe the scent of a peach for English class. A friend told me how he grew up wondering why “red” and “green” distinguished between two different shades of brown, when really, he was just colorblind. The other day, I learned that not everyone has an internal monologue.

The thing about brains is that it’s so easy to assume that other people’s brains work the same way. We can communicate perfectly fine, if we do the same things from the outside. And yet, what can be “visualization” to you might not be what “visualization” is to me.

The scary thing is that there’s no way to find out, unless we talk about what our experiences are like, and trust each other to mean what we say we mean.

Two pivotal experiences in my parents’ married life happened shortly after I was born.

My parents had plans to move to Boston and work here. My mother was a bank teller, at the time, although she took nursing in college. She took the NCLEX and got a job offer somewhere. My father was a professor, at the time, and got an offer for a research position somewhere. This was why I grew up speaking English as my first language, as my parents didn’t want me to be alienated when we moved. Whenever my mom would recount the story, she’d mention that we already had visas, even. Pretty much everything was set for us to go.

One Sunday morning, during a church service, my mom heard the voice of God, urging her to stay in the Philippines. She called my dad, who was shocked, but understanding. After some discussion, they eventually decided to stay in the Philippines.

Around a year after this happened, my father turned thirty. He was a pastor at our church, while still working as a professor. Along with several other church leaders, he went on a retreat somewhere along a mountainside. During this, he had a spiritual experience, in which he heard the voice of God, urging him to quit his job and become a full-time pastor. By the end of the year, my father was no longer a professor.

For most of my childhood, then, my father was a pastor, my mother was a church leader, and the church was our life. My family twelve to fifteen hours in church over the span of a week. To be a full-fledged member of the church, there were two important requirements: the first was to be baptized, and the second was to have a spiritual experience, such as hearing the voice of God.

And so I got baptized. I went to church, twelve to fifteen hours a week. I spent a lot of time in prayer, in meditation, in worship, waiting to hear the voice of God. I was raised believing this was a big deal, as the voice of God steered the direction of my family’s life. The closest thing I experienced was internal monologue that sounded like it couldn’t have been mine.

Fourteen-year-old me called this the voice of God, and didn’t think twice about it. He became a member of the church. He shared testimony about hearing the voice, and the other members of the church said amen and clapped and gave praise to God, for making the voice known to me. Everyone, including me, believed that I was hearing the voice.

And yet, when other people described their experiences, they talked about how the voice was something clearly audible. As if someone was standing above them, and speaking to them, directly. My experiences were never that vivid, and so I thought they were simply speaking in metaphor, or exaggerating. I never thought about sharing what I experienced the voice to be like. What if I’d get rebuked for not actually having heard the voice? Would I be a bad Christian, then?

The fear had paralyzed me, stopped me from thinking about it too much. Slowly, my devotion transformed from being faith-driven to fear-fueled.

As it turns out, most people don’t have depression. Not to mean that most people are always happy, or that they don’t get sad, or that they don’t grieve. It’s just that most people don’t suddenly lose interest in activities they used to enjoy, or have chronically low self-esteem, or wake up in the morning wishing that they were dead.

This realization was mind-blowing to me, and even now when I think about it, it still is. It’s hard to imagine what my life would be like if I was never depressed, but it’s even harder to believe that most people aren’t. I think what actually convinced me this was true was when I thought about how much I complained to my friends about how much I hated myself, versus how much my friends complained to me about hating themselves.

The onset of my depression was when I was fifteen years old. Disillusioned by church, struggling with my social life, and exhausted spending hours upon hours each week pretending to be a believer, I became depressed. I lost motivation to do schoolwork and spent a lot of my time lying down in bed, browsing random websites all day.

My mom first confronted me about it when she saw I had drawn a line over my wrist with a marker. She asked me if I was feeling “that suicidal thing”. Her tone carried utter disbelief, like she couldn’t believe I could ever feel depressed. My mother berated me and warned me to never do that again.

In retrospect, I can understand why she’d reacted like this. How could I have felt suicidal when she has never felt that way? How was it possible for anyone to feel suicidal, then, if she’d never experienced it? This, coupled with cultural stigma around depression and a church-sponsored disbelief in mental illness, explained her reaction pretty well.

For several months after that, I juggled my responsibilities and kept up my pretenses. Gradually, however, the balls began to fall and the masks began to crack. At the end of tenth grade, we were asked to write down what our ambitions were, which would be printed in our yearbook and displayed during our end-of-year ceremonies. Others had written things like “to be a successful doctor” or “to be an engineer”. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life, so on a whim, I wrote “to be truly happy”.

The faculty had confronted me about this, concerned that something was wrong. They’d understood that I had problems with my home life, so they made the decision to call my parents. In a meeting with the principal, as I sat in front of her desk next to my mom and dad, I broke down and confessed the feelings I had been hiding from my family for months. That I was depressed, and that I no longer believed in God.

In the office, my father had been understanding. He said that I would still be his son, no matter what I felt or believed in. We came back home that day and ate dinner. A few hours later, my dad knocked on my door and asked to talk. As I discussed my feelings and my doubts, he erupted in anger, and smashed my phone against the floor. He threatened to kick me out of home if I insisted on being an atheist, and so I cried, I pleaded, and I said I would make an effort to believe again.

That day, I had come to learn that I was not the only one who knew how to wear masks.

My parents believed that depression, or indeed, mental illness in general, wasn’t “real”. Instead of being caused by a chemical imbalance, or being triggered by certain events or stressors, someone becomes depressed if, through their actions, they have invited the spirit of depression to gain a foothold into their life.

I had lots and lots of arguments with my parents about this. About how awful depression was, about how serious mental illness was, about how maybe I would feel better if I wasn’t being forced to pretend all the time. It was all nonsense to them, words that weren’t mine but of whatever demon was possessing me. The most basic level of empathy we can give to someone is to trust what they say, and if my parents couldn’t offer me that, it was hopeless to reach out.

If the disease was a demon, then the cure was an exorcism, the casting out of whatever spirit had taken root in my soul. So I went through an exorcism. A pastor laid his hands on my shoulders, gave the demon authority to speak through me, asked for the demon’s name, and used the name to drive the demon out. The process is a whole story in itself, but needless to say it didn’t really help in making me feel any better.

I don’t want to invalidate the experiences of people who’ve found respite from depression through their beliefs; that’s great. But it’d be nice if the solution to all mental illness was as simple as sitting with a pastor in a room for an hour.

Although I don’t believe that demons were the cause of my depression, the metaphor holds some water. Depression feels like a demon pressing on my shoulders, like constantly carrying a backpack filled with rocks. It’s waking up already exhausted, already starved of energy to go through the day. It feels like a demon writing down negative thoughts in my stream of consciousness, like a demon pulling down the mental lever of how much I liked myself, and in the worst nights, like a demon showing me a movie about how I die.

For someone who’s never experienced depression before, this may sound hard to believe. Was I speaking metaphorically when I talked about the weight on my shoulders? Was I really depressed when I could still pass my classes and do work? Was there really an entire spectrum of emotional pain out there, that many would never, ever feel? To these questions, I respond with another: would it really be that surprising if other people’s brains work differently than yours?

To be truly happy, then. How would I know what that felt like? Would I ever experience what it’s like to not be depressed? Will it just be one of those things I would never understand, like visualization or sexual attraction, something that my brain just wasn’t configured to do?

I spent nights agonizing myself over these questions, crying myself to sleep over this ungraspable pain.

Although I still haven’t experienced what it’s like to not be depressed, I’ve made steps toward that direction.

The biggest step I took towards getting better was leaving home. The burden of pretending to be someone I wasn’t was lifted from my shoulders. In its place came guilt, guilt about how I related to the rest of my family, and that guilt followed me around for months. Now I’m in MIT, oceans away from my parents, and yet their ghosts still haunt me every now and then.

Here at MIT, I’ve met people who’ve acknowledged my problems. I went to Mental Health, I talked to a therapist, I took medication. I spent my time studying and meeting people and making friends. To know the name of the demon is the first step in driving it out. To have people empathize with my situation made me feel better, even if only by a little.

Don’t get me wrong. My life at MIT has been filled with struggle: the struggle to get better, the struggle to know myself, the struggle to chart the future. But it’s not as bad, not as bad as my life back with my parents. For here, the struggle is married with strength: the strength of institutional support, the strength of being truthful to myself, the strength of friendship. It’s hard, but I’m stronger.

I count the tiny victories. I surf through the nights one-by-one, each night another that I’ve chosen life over death. The more nights I put between me and my parents, the looser the demon’s grip gets.

Last Saturday marked the thousandth night since I’ve seen my parents.