Downtown by CJ Q. '23

if you could see it then you’d understand

Saturday, 11 AM. Alan Z. ’23 sends me a message.

Alan: what do you have to do today/do you want to meet at like Downtown Crossing between like 12:30-1 and walk around Boston

CJ: i have hw

CJ: but fuck that

CJ: we can meet

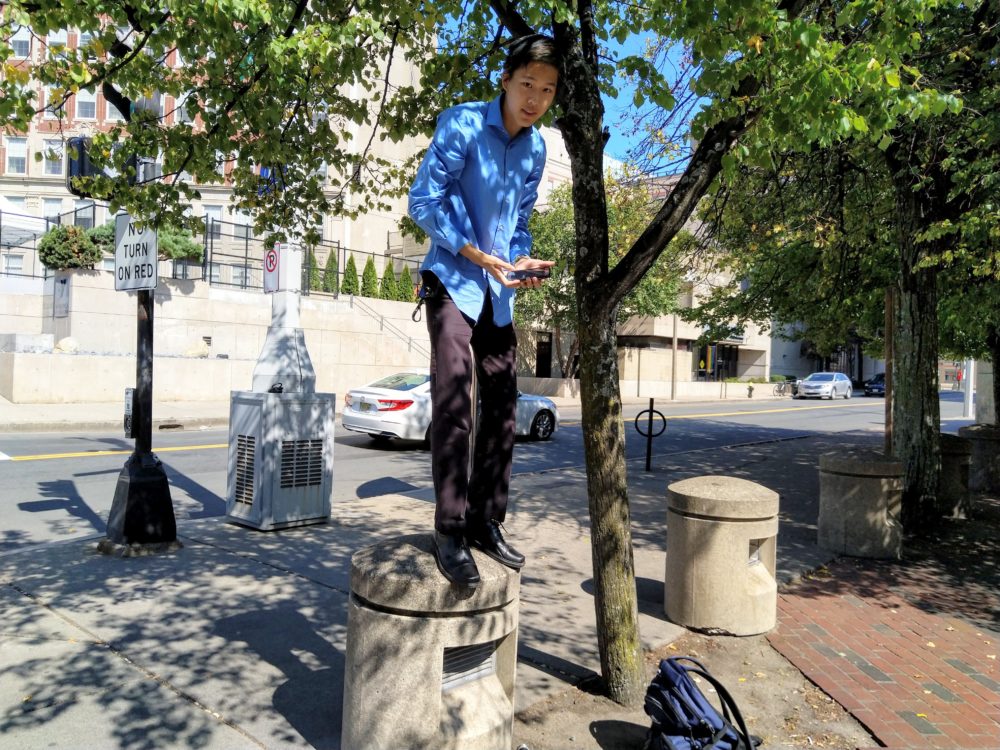

Two hours later, we’re at Park Street, one of the stops on the Green Line. It’s warm out. He’s wearing a long-sleeved button-down and slacks; I’m wearing a t-shirt and shorts.

“Couldn’t be wearing anything more different,” I say.

We walk around Boston Common, this big central park in the middle of the city. We talk. He just came from debate at Boston University, a few stops down the Green Line. They debated asteroid mining and supreme court justices and driver’s license applications.

I suggest we walk in a direction neither of us know. Alan knows downtown better, so he chooses where to go, and we start walking.

The first thing we see is a building.

A huge, windowless, cylindrical building. Imagine the MIT Chapel, but larger. Larger. Towering.

“It’s a very weird building,” Alan says. “So out of place.”

He’s right. All the buildings around it are aged brick rectangles with fancy window frames. But this is different. It’s out of place. Like a round peg trying to fit in the square holes of Boston architecture.

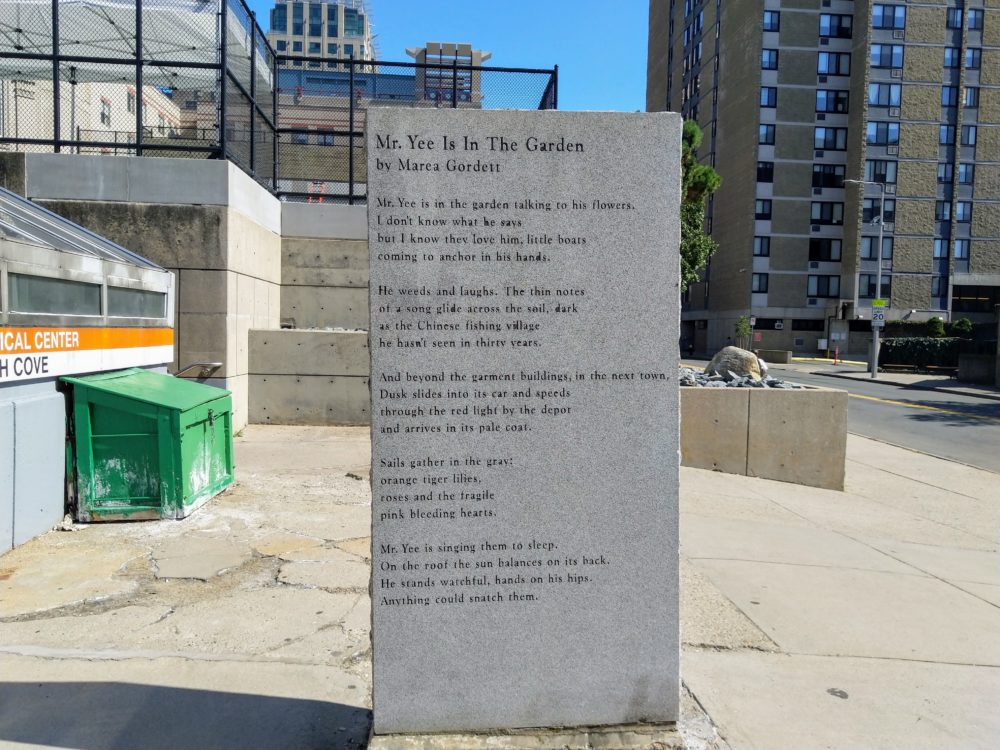

We walk past a small park, and cross a couple of roads. We spot a poem:

One stanza, in particular, strikes me:

He weeds and laughs. The thin notes

of a song glide across the sail, dark

as the Chinese fishing village

he hasn’t seen in thirty years.

“It looks like this way is Chinatown,” I say, pointing to the streets in front of us.

“Not unless Chinatown is this thin strip, and that a few streets after this you leave Chinatown,” Alan says.

I reply, “Well, if you keep walking forward, you’ll eventually leave Chinatown. Unless we’re in a horror movie and we’re permanently stuck here.”

“That wouldn’t be too bad.” He chuckles. “I could spend the rest of my life stuck here.”

Right, I say. You can read Chinese.

I can, he says, but only simplified. He explains that in Chinatown, everything’s in traditional Chinese. Talks about how the people who live here moved from a long time ago, before simplified Chinese was standardized.

Further down, we spot some murals, and some stairs leading up to some unknown structure.

There’s a mural on the lower-right of the picture. The sign next to it has a list of names. Fifth graders, sixth graders, who worked to make the mural together. Apparently it’s an elementary school. The signs warn, no trespassing, which does not stop us from taking pictures.

We walk a bit more. We get lost in this side street, away from the main roads. There was a small park, no wider than twenty meters in any direction. Open to the public, privately owned. Flanked on either side by seven-storey high apartments. We sit on a bench.

photo: alan z. ’23

We talk about what it means to be Filipino, or what it means to be Chinese. We talk about language, and how culture is carried through it. We talk about being a second-generation immigrant. How a lot of Filipino-Americans don’t speak Filipino, or how a lot of Chinese-Americans don’t speak Chinese.

Alan introduces to me the phrase living on the hyphen. How Chinese-American is neither Chinese nor American; but somewhere in between. Couldn’t be any more different than either. Out of place.

As if you could box culture to be a single thing, I say.

We head up the ramp, which leads us to a highway. Alan notices a sidewalk on the other side. So we cross.

“I want to see where this sidewalk leads to,” Alan says.

It’s a long sidewalk. Takes ten minutes to walk down its length. But there’s a nice view out. We have the time. We have things to talk about.

The sidewalk is level for a while. And then it leads down.

On the sidewalk, colorful lines begin stretching out towards the horizon. It looks as if someone traced them out with chalk. In the distance, under the highway, we spot murals.

More and more lines appear. Dozens. They weave into each other. Pink, blue, green, yellow, white. They’ve faded a bit, but they’re all following the sidewalk.

It heads down, and then veers left, leading us underneath.

The sidewalk widens into a path. A sign tells us where we are: the Underground Ink Block. A couple of cars are parked near the highway. We spot dozens of murals in the background.

We head in.

And it’s colorful.

There’s a stark contrast between the Ink Block and the surrounding areas. There’s so much color and so much art. It feels so lively; the only thing missing is people to enjoy it. It’s different from the brick and glass and concrete and asphalt, different from the aged beauty that was Boston, different from the thin coat of modernity wrapped around its buildings.

The Ink Block leads out to a bridge, which leads to the Broadway station on the Red Line. Overlooking the bridge are some parked Red Line trains.

photo: alan z. ’23

photo: alan z. ’23

We walk to Seaport, and spot some ducks. We eat mac and cheese at this vegan cafe, then visit the Institute of Contemporary Art. (MIT students get free entrance.) We take the Silver Line bus to South Station, then the Red Line to Kendall, and then we are back home.

The Ink Block wasn’t really one of the stops in our walk. Not that any of the stops we made were planned, but it wasn’t really an endpoint; it wasn’t somewhere we stayed at for a long time. We spent five minutes there, and then we left.

It served more like a link between two places, like the hyphen that joins two words together. It was a brief moment where it felt like we stepped out of Boston into this new country. We were engulfed by silence that begged for noise, begged for sound. We were surrounded by color, so much color, so much color boxed in this single place.

Because hyphens can be colorful too.

All that noise, and all that sound

All those places I have found

And birds go flying at the speed of sound

To show you how it all began

Birds came flying from the underground

If you could see it then you’d understand