My Final Blogpost by Vincent A. '17

With a heavy heart, I say goodbye to the MIT blogosphere. The journey was all too short, but it was wonderful.

And psych!

Happy April Fool’s Day!

I didn’t celebrate it in particularly grand style, but I do plan to give some of my friends heart-attack-worthy lies over the next couple of days. And this blogpost is all about the art of lying. We all know good lies contain a grain of truth, like how CPW shows that MIT is a series of nearly back-to-back all-nighters, except that events, games and making new friends are replaced with p-sets, p-sets and chatting with hosed friends. Well…don’t take my word on that. Nah, actually, you probably can.

It’s been a few days since Spring Break ended, and the break was truly wonderful. Apart from spending a great deal of time writing new short stories, I saw and spent time with my mom. I hadn’t seen her in nearly nine months, so I was shaking with all the excitement of an excited train guy howling about trains and then infinitely more. It was a beautiful week.

Now, I’m back to the usual battle with problem sets and stubborn, crashing codes. Taking breaks like this to write is always a cause for celebration.

And, on the surface at least, that’s what this post is about.

“Fiction is the truth inside the lie”—Stephen King

I like writing about MIT, about the tumbling rollercoaster rides and endless head-bashing we face against problem sets, about the students, about wondering if the Alchemist Statue will one day rise and kill us all.

You can almost feel its venom building up like Voldemort’s, just before he melodramatically shrieks, “Avada Kedavra!” at Harry Potter in the penultimate forest scene of the final movie.

I see you, evil statue.

I know your plan.

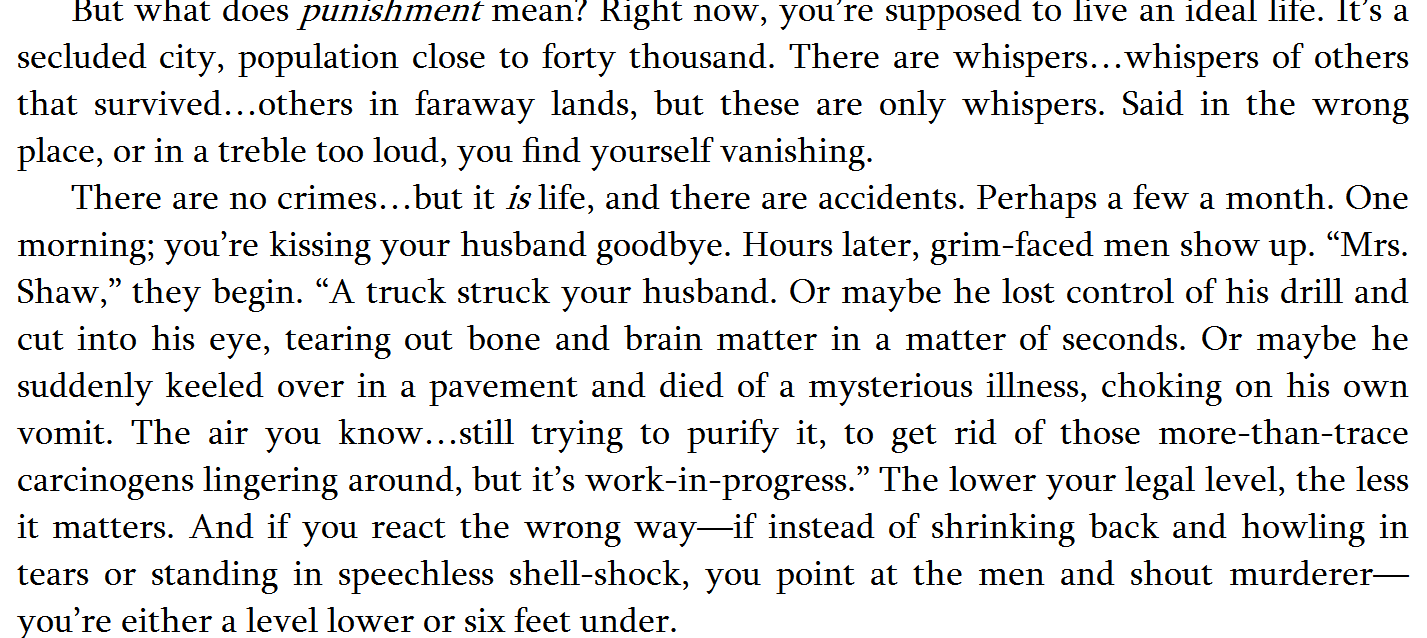

But as much as I enjoy writing for the blogs, I spend the bulk of my time writing about imagined worlds, about heartbroken moms and bullied kids, depressed serial killers and cautious illegal immigrants. At this point, I must have written at least a hundred different stories, most of them unfinished. They kind of just sit impatiently in my Documents Folder, bidding me to hasten and complete their worlds. Except that each snippet of a plot I type up doesn’t feel like a world I’m creating. It feels like one I’m discovering. These people, with their dreams and their stories, escaped from some universe, a piece of a jigsaw puzzle I’m privy to. And the more time I spend with them, the more pieces jump out; the more I begin to see where they want me to delve into.

From memory, my earliest attempt at a story occurred in grade four. I wrote an 84-paged tale titled, “The Cries of Emeka”, a literary atrocity that spewed prose with all the harmony of brain-dead chimpanzees banging on drums. My saving grace existed in my cluelessness. I had no idea I was such a terrible writer, and thus, I wrote more frequently.

Just before grade 7, I had my Star Wars phase, and was so awestruck by the movies that I instantly wanted to find a world like that. From this, Sagittarius was born. Sagittarius may be my most meaningful endeavor yet, one I began over six years ago, one that I’ve barely scratched the surface of, as of today. I spent all of high school writing this six-part sci-fi series, about a planet called Sagittarius, one of many in a collection of star systems ruled by the Cosmotic Federation. Wha? Well, that’s not really a good description, but as the plot tends to meander in all directions I’m clueless on how to summarize it. I completed Sagittarius in grade 11. The first draft at least. I had written everything on paper (my boarding high school was very anti-laptop. And pretty much anti-anything that could be associated with batteries). At its completion, there were two thousand or more pages. Only two people had read the entire thing, and their inputs played much part in what feels like my formative years. After completing Sagittarius (the first draft at least), I decided to go on a writing hiatus. At several moments, writing had clashed with my academic work. Even at moments when missing classes to study for the IMO had me really hosed, I still gave large portions of my time to writing, and as drawn as I was to the art of having characters do stupid plot-convenient things (snerk), I knew I couldn’t keep it up for long.

Which was really just a stupid lie because as long as I wanted to keep it up, I could. And thus, the break following grade 11, when my family and I saw news of a kidnapping, when my parents began talking about it, something flew in. It was a man, bloody-faced and bound in ropes. I wasn’t seeing him on the television. He was somewhere in my mind, writhing in agony. He was trying to say something, but I couldn’t make much from his muffled croaks. And I instantly knew I wanted more.

A new phase began. Over the course of months, I began to see more and more of the man’s world, and the people around it. When I couldn’t connect the dots floating in my head, I tried to force some connection, but as long as it didn’t feel right, as long as it didn’t feel natural, I refused to move on with it. By the end of my final year, I had enough of the pieces to begin drawing life into them, to begin dragging these people out of my head and flooding them into an empty 11KB Word Document.

The writing process is, at its peak, a delightful and immersive process. I’ve found that the more involved I was in a story, the more my heart and mind seemed to tie themselves around it. I remember writing a story two months ago about a family of illegal immigrants. I didn’t know much about the issue as it related to the US prior to writing the story, but I had a little piece of it with me, and I was convinced that to discover the rest, I simply had to know more about the issue itself. Cue to a long, near-sleepless night spent on Wikipedia and government pages and blogs and mini-documentaries. And I suddenly knew what had happened to the characters in my head, what had to happen.

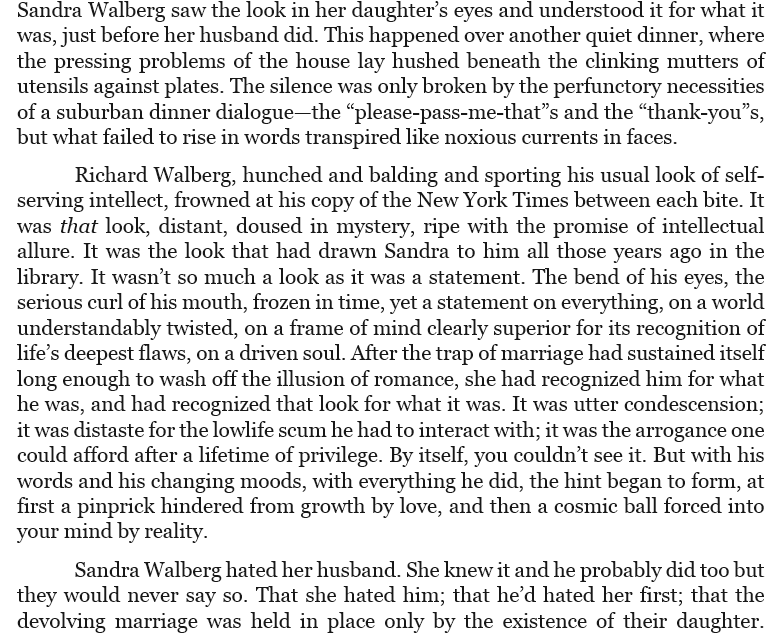

The stories I write are typically dark—I have no idea why; they just seem to mold onto the shapes of the vulgar and the sinister. And for this specific scene, I found something wrong with me. I was supposed to describe a death—a man close to the main character had met his end in a graffiti-ridden alleyway, his belongings stolen, his throat slit. And when the main character found out, as I typed up the words of his discovery and his shell-shock, I felt two layers.

There was the exterior layer, the blank-faced me, just typing the words, just watching the scene play out from somewhere intangible. And then there was the interior layer, a blend of myself and the character. I could feel his horror. I could feel his pain. It was a kind of distant pain, hushed by the presence of the exterior, but it still felt raw. It still felt real. And as heartache was inflicted on this person that I was cared about, the words just bled onto the page. Yes, he’s trying to say these things. No, he can’t. He’s just standing there, paralyzed. His mouth is open and I can see it. I can see the people around him. I can feel the heaviness in the air, a toxic charged cloud that seems to hold everyone’s joints in stasis.

And this is what writing fiction feels like. When writing about the serial killer, you’re suddenly the serial killer. You see the victim from his excited eyes. You can feel his breath puffing up your throat and out your lips on this warm night. You can see why he has to do it, why the girl has to die. And you can feel him charging forward, his shadow winking in and out of a line of trees. And suddenly, you can feel the girl as he draws her up close. You can hear her screams as his knife comes down. You can feel the resistance as a cold blade meets the bone beneath warm flesh.

And when you’re the girl’s mother, standing in court and staring at the face of the killer, you’ve forgotten the wash of emotions that overwhelmed you as the girl died. You see nothing but a repugnant, hateful, disgusting man. Your grief and fury can’t be expressed in enough words, but you can feel it and you can attempt to transmute it into letters. You can feel the impulse to reach for his face and break it. You see your girl, think of her smile just before she slipped out into the night. You remember how you almost called her back—just a thoughtless whim at the time (too cold out dear, just come back in and go tomorrow). But now, now, it could have been everything. The line between salvation and demise.

She’s dead. She’s gone forever.

And suddenly, you’re not the mom, but an observer, riding the clouds and watching the lives of these people play out. And somehow, you know that there’s a lot the mom doesn’t know. You know that when she steps out of the court, a set of intricate dominoes will fall, dominoes set up by another person. You know that she will soon meet the same fate her daughter did.

***

And when I’m writing, the world around me just fades. People mutter, songs play, cars zoom by, but I don’t know about any of that. I don’t care. What matters now are the people and their world, a world I’ve spent ages trying to piece together, to delve into, a world that I now understood well enough to talk to you about. I used to care about how good my stories were, how real my characters were. But I don’t anymore.

While I still try to take writing classes and soak up as much lessons of literature as I can, I never let the fear that my writing might suck stop me from typing the stories I want to type. But this wasn’t always the case.

***

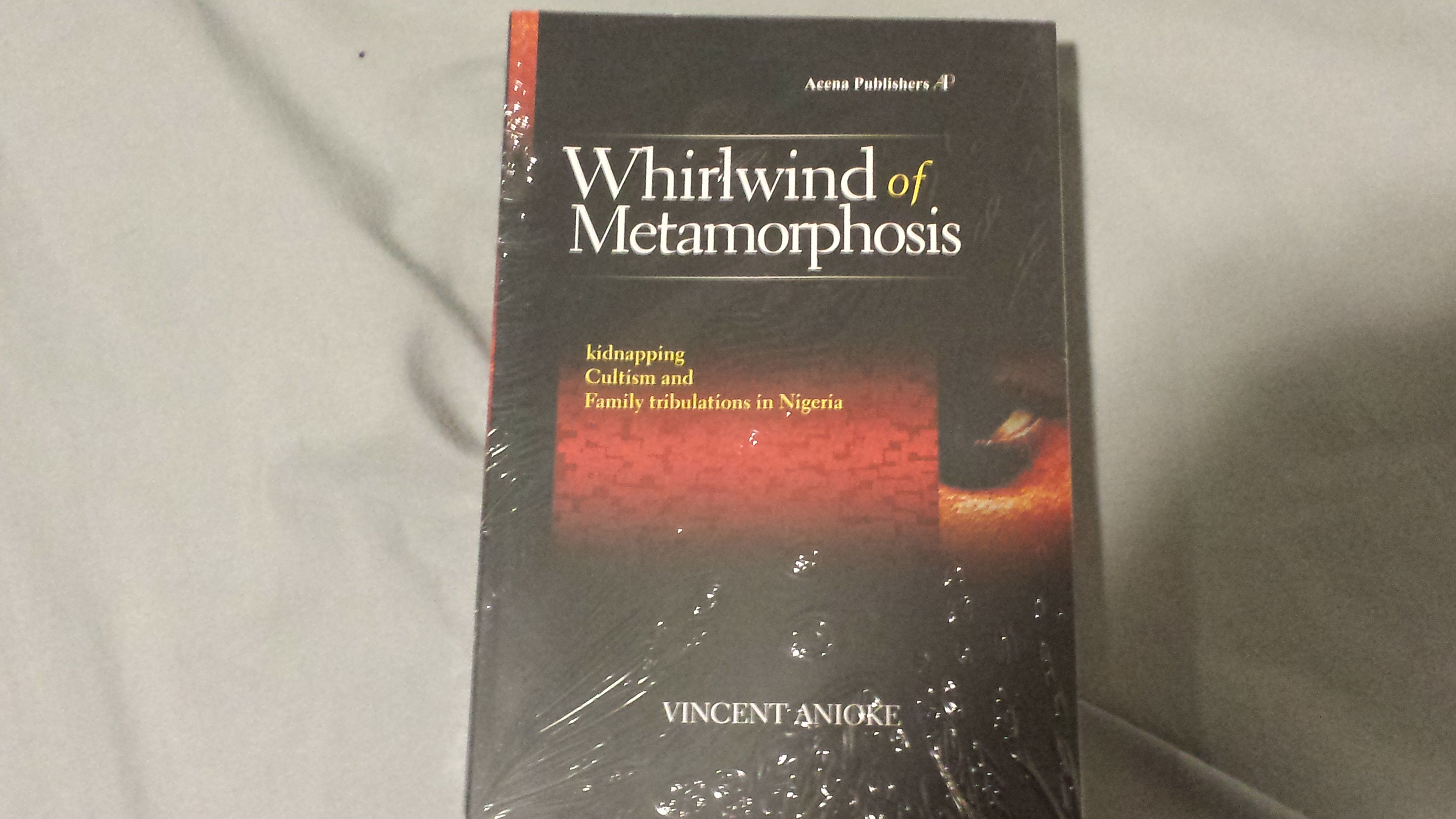

The last huge piece of writing I typed up, over the course of my gap year, is titled, “Whirlwind of Metamorphosis”. It’s set in Nigeria, and describes how a kidnapping initiates a series of increasingly worse events on a family. My cousin read it over Spring Break and wondered why so many awful things were happening. When we discussed it, I wasn’t entirely struck by how many hopefully heartfelt compliments she had to offer, despite the overall morbidity of the characters’ situation. I was awestruck by how she talked about them the same way she could about people she’d seen in the news, real people somewhere out there, facing real problems.

And it took me a while to realize that even if she had thought differently, say, even if she had thought they were two-dimensional cardboard characters, spewing the kind of stereotypical crap we might expect people of their profiles to spew, it wouldn’t matter. I always set to every story with the best of intentions. Flaws were more than inevitable; they were necessary. I had to be aware of their existence, but I wouldn’t let them hold me back.

I realized this when, halfway through Whirlwind of Metamorphosis, I stopped writing the story. I wasn’t sure of its sense of direction. I wasn’t sure of its artistic merit. It felt like a tumbling mess of words penned by the typical trite monkey with a typewriter. And so for two months, I did other things. I watched TV shows and solved math olympiad problems. I taught at my high school and transferred the contents of the home refrigerator into their true home—my stomach. I did anything but write.

My mom wondered why. She’d known I was working up a story. I’d actually told her some of the starting events. And she wondered why I wasn’t writing anymore. When she realized that I wasn’t jaded or burnt out, just afraid and uncertain, she went along the lines of “Well, even if what you write makes no sense, it’s still several pages better than something that doesn’t even exist”.

I did end up finishing the book.

And it did end up getting accepted for publication.

On print, it came out to about 547 pages.

***

Why did I start writing anything in the first place? Why do I decide to write anything?

I don’t know. The answer my mind wants to give goes along the lines of: there are things my mouth can’t utter that my hand can; there are feelings I can’t voice to an ear that a page can hold in confidence. I write because I have something to say, if only to myself. And this feels right. But in all honesty, there’s such an element of joy, of fundament, to writing. It’s such a big and indispensable part of my life that the more truthful answer seems like: I have something to say because I write. Writing has been with me from the onset, and it’s empowered me to describe things that would have otherwise had no voice—from intimate secrets to ghastly tales.

And to you, friend, still somehow reading, I know that there’s something that makes you light up. Whether you can describe it or not, there are things that you just want to pursue and jump into with tidal fury. Things you love. Things you think you could love if you tried Pursue them. The more you do, the deeper into yourself you’ll seem to collapse. These things will tie themselves so deeply to you that their growth will mean yours. And when fear comes, gnarly, mutated, rising from the shadows, when you begin to get doubts, and when you begin to lose motivation, remind yourself that you’re really doing these things for yourself. And why should it matter if they’re imperfect or error-ridden? They’re for you. When you’re not thinking of others, you’re able to enjoy them, and that’s really what matters.

I don’t know what the future holds. I don’t know if I’ll ever publish another book or if I’m destined for a lifetime of rejection slips from apologetic publishing presses. But I know that no matter what, I’ll always want to write.

***