Navigating MIT is like flying a spacecraft* by Michael C. '16

the most important things I've learned here so far

In spaceflight, “attitude” refers to orientation: which direction your vehicle is pointing relative to the Sun, Earth, and other reference points. If you lose control of your attitude, two things happen: (1) you start to tumble and spin, disorienting everyone on board, and (2) you start straying from your desired course.

In short, controlling attitude is one of the most crucial parts of flying a spacecraft, which is why they’re equipped with suites of sensors and actuators dedicated to monitoring and adjusting orientation.

Life at MIT isn’t so different.

You might get sick during finals week. You might have a midterm and 3 psets due on the same day. These are variables that you have little control over.

What you do have control over is your attitude.

Attitude is really important. It’s what keeps you going through hell weeks, what keeps you going after you bomb a midterm, what keeps you hitting the books when all you want to do is sleep. Because if you don’t maintain attitude, you’ll be like that spacecraft tumbling out of control – going wherever life shoves you.

*(Credit for this analogy goes to retired astronaut Chris Hadfield. You should get his new book – it’s really good!)

During my time at MIT so far, I’ve learned some valuable lessons about maintaining attitude:

1. Failure is an option

Most people go into MIT used to success. Between hard work and natural ability, they’ve always been reasonably successful at most things they’ve put their minds to.

And depending on your strengths, you might coast through a few semesters at MIT too. But sooner or later, everyone hits a wall.

One of the hardest things I’ve had to learn at MIT is: hitting a wall is okay! Actually, it’s great! Because if you’re not hitting walls, then you’re not pushing yourself hard enough.

Early success is a terrible teacher. You’re essentially being rewarded for a lack of preparation, so when you find yourself in a situation where you must prepare, you can’t do it. You don’t know how. Even the most gifted person in the world will at some point cross a threshold where it’s no longer possible to wing it. The volume of complex information and skills to be mastered is simply too great to be able to figure it all out on the fly. Some get to this break point and realize they can’t continue to rely on raw talent— they need to buckle down and study. Others never quite seem to figure that out and, in true tortoise-and-hare fashion, find themselves in a place they never expected to be: the back of the pack. They don’t know how to push themselves to the point of discomfort and beyond. – Chris Hadfield

If you’re maintaining the right attitude, even the most excruciating failure can become a valuable asset. I know from personal experience:

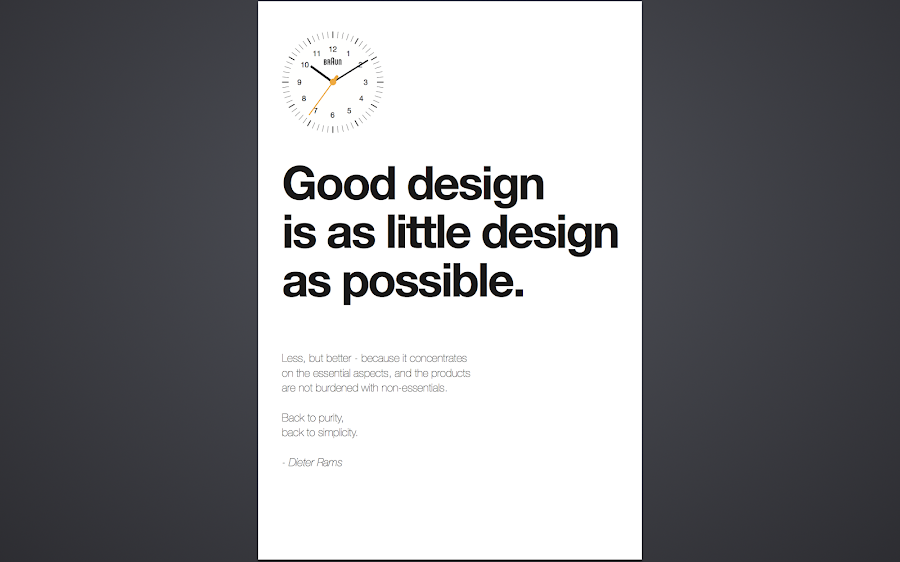

I’m passionate about the intersection of engineering and design. It’s the reason I took 2.00B (Toy Product Design) last year, and also the reason why I made this giant Dieter Rams poster hanging on my wall:

I think there is a profound and enduring beauty in simplicity, in clarity, in efficiency. True simplicity is derived from so much more than just the absence of clutter and ornamentation. It’s about bringing order to complexity. – Jony Ive

To me, design is so much more than just the way something looks. It shouldn’t just be some aesthetic shell that you slap on after the engineering team has cobbled something together. True design is the very core of a product, which manifests itself in successive outer layers. It’s how the product works, how it feels in your hand, how it fits in the context of your life. And the very best products come from places where engineering and design drive each other.

Apple is probably the company that most embodies this design philosophy, which is why I’ve always dreamed of joining their Product Design group.

So in late September, when Apple recruiters visited MIT, I leapt at the chance. My first casual interview went well, and I scheduled a second interview the very next day.

I prepared, and prepared, and prepared. I went to the career development office for mock interviews. I obsessed over my resume in LaTeX. I even timed the walk from campus to the coffeeshop where the interview would be to make sure I wouldn’t be late. This was my dream internship, seemingly within grasp.

I bombed the interview.

The behavioral portion of the interview went well enough, but most of the technical questions were on material in 2.001/2.002 (Mechanics and Materials) that we hadn’t covered in class yet. And so I stumbled, red-faced, through the questions – I’m still cringing at the memory. (Specifically, I remember getting certain material characteristics of polycarbonate completely wrong, claiming that it’s an ideal material for when scratch resistance is important – forgetting, of course, that polycarbonate actually has very low scratch-resistance and has to be coated to increase its durability. Why do I still remember this?).

This sort of complete academic failure was new to me. But as badly as the technical interview went, I chose to view it as a valuable learning experience – as a wakeup call. As the semester rolled on, I began recognizing the stuff we were learning in 2.001 from my interview – and you can bet that I learned that material extra well (in fact, I got my best test score this year on that section!).

And a few weeks later, I got another email from Apple. The iPad product design team wanted to set up another interview!

This time, I was much better prepared. I knew what to expect in interviews now; I knew what my weaknesses were. And I solved the brain teasers reasonably well. Results won’t come out for a few weeks, but either way – I am satisfied that I did everything I possibly could to prepare, and therefore I am content.

Failure has worked out pretty well in my favor.

2. Work towards a goal – but don’t cling to it

If you go into MIT thinking that you’ll major in whatever you find “interesting”, you’ll never get anywhere.

It’s like being a kid in a candy shop; very little work at MIT isn’t interesting. You’ve got to go beyond interest. You have to find what truly excites and challenges you. As Dropbox CEO Drew Houston told MIT in June:

When I think about it, the happiest and most successful people I know don’t just love what they do, they’re obsessed with solving an important problem, something that matters to them. They remind me of a dog chasing a tennis ball: their eyes go a little crazy, the leash snaps and they go bounding off, plowing through whatever gets in the way…

It’s about finding your tennis ball, the thing that pulls you. It might take a while, but until you find it, keep listening for that little voice.

You don’t need to know exactly what your goal is – but you should have one. Every decision you make today turns you into who you are tomorrow, and the day after that – so you’d better have some end goal in sight. Otherwise, you’re just going through the motions.

You probably won’t end up exactly where you think you’ll end up – who’d want the rest of their life perfectly planned out by an 18-year-old anyway? – but you will be doing things that excite you in something that matters to you.

Having a concrete goal is the major reason this is the happiest I’ve ever been at MIT. I’m taking classes that excite me, and I can see the direct utility in the material I’m learning (thanks, bombed interview) – and therefore I know I’m moving towards my desired goal.

Find your tennis ball, and chase it. Don’t just go through the motions.

3. Ask for help

MIT is hard. You know what’s even harder? Going through MIT alone.

Office hours, recitations, upperclassmen, S^3. These are all really valuable resources that I did not take full advantage of last year – out of some misguided sense of lone-wolf-ism, or something.

But I’ve since realized that I lack the gene for masochism. You don’t get extra credit for grinding through a pset alone for 3 hours, versus asking for help.

There will always be people in your classes who brag about how they never have to study or go to recitations or lectures. Ignore them.

There is no shame in asking for help. The only shame is in not getting where you wanted to go, because you were too afraid to ask for help.