on body image by CJ Q. '23

me in my head, me in the mirror

One. It’s the first time I’m seeing Sean in three months. He’s the person living nearest me whom I’ve known for the longest—I think we’ve been friends for four or five years now. The first observation he makes upon seeing me? That I’m fatter now.

It’s Filipino culture to comment on people’s bodies when you greet them, especially if they’re someone you haven’t seen for a while. Tumaba ka ata—looks like you’re fatter now. Ang haggard mo ngayon—you look exhausted today. Ang payat-payat mo na, kumakain ka ba nang mabuti?—you’re so thin, have you been eating right?

Like many cultural phenomena, it’s something that makes more sense if you know the culture better. It isn’t generally taken as a comment made in bad faith, especially among older Filipinos. An honest observation about the person you’re talking to is supposed to be a sign of concern; that they care about you enough to both remember what you’ve looked like before and inform you of the change now.

Another factor is that, despite taba in Tagalog meaning the same as the English fat, the connotations feel different. Being mataba is linked with being malusog, “healthy”, particularly in contrast to being buto’t balat, “skin and bones”, which is viewed as a sign of malnourishment. To eat food and to grow fat is a privilege afforded to people who had food in the first place.

Placed in that context, how did it make me feel? Nothing, honestly. When I took a gap year before coming to MIT, my friends at home would tell me, all the time, that I’ve gotten fatter. That my face is rounder, that my belly’s bigger. In this context, Sean’s remark wasn’t really an insult, and more like an inside joke, a reminder of the culture that we shared.

Two. Except that’s not entirely the truth.

Like many cultural phenomena, the connotation of being mataba has changed over time. I’m speculating here, but it feels like there was a shift around the late 90s to early 2000s, bringing it closer to conventional Western views on being fat. Being fat was cast as being unhealthy. It became linked with hypertension, and certain kinds of food were viewed as causing high blood pressure, or nakaka-high blood. Stuff like that.

I grew up during this shift, so I’ve been influenced by this view. As much as I wanted to pretend that I didn’t feel bad about my friends saying that I was tumataba, the truth was that it did feel bad. When it first started happening, I paid more attention to what I was eating. I told myself that I was doing it to be healthier, because it’s good to have a good diet, right?

Sixteen-year-old me would only realize it much later, but there are deeper reasons. Part of it was so that people would stop commenting on my weight. And part of it was because I thought it would make me look more attractive. I wanted to be thin! I wanted abs. I wanted lighter skin and a better-shaped nose, matangos na ilong.

These were all pressures that have been drilled into me by the people I talked to growing up. Stories of “the freshman twenty” made me want to eat less. My friends telling me to hit the gym made me want toned arm muscles. My parents telling me to use this “skin-whitening soap” made me want paler skin. Them telling me, back when I was five or six years old, to pinch my nose so that it’d be sharper mad me want—well, you get the picture.

And there’s nothing wrong with going on a diet or wanting to exercise more! But maybe there’s something wrong if my motivation was to become more attractive rather than becoming healthier, to impress other people rather than myself.

There’s been a pushback on the practice of greeting people with ang taba mo na, that I understand to be relatively recent. And I think that’s great. It’s great that people are pushing back against this, because people should be able to feel good about their bodies, no matter what they are.

Right?

Three. Here’s a list of some memories involving my parents:

- I was maybe seven or eight years old, walking to the kitchen. My dad said that I walked like a girl. My mom asked me to walk a few steps in a straight line, and my dad said I shouldn’t swing my hips around so much when I walked.

- I guess I was ten years old, playing Pamela One with some friends. It’s this sort of dance game… I don’t remember much about it. What I clearly remember was my mom walking in on me and saying that I shouldn’t be playing that game, because it was “for girls”.

- I think I was fourteen? It was summer. My hair was getting long. My dad handed me a fifty-peso bill and told my to get a haircut, saying that my long hair “was beginning to look like a girl’s”.

My parents had always insisted that I present as male, being deeply homophobic and all that. I didn’t really question it until I turned seventeen and ran away from home, which was when I began exploring how male I actually felt, without fear of my parents killing me if they found out. Not that I had gender dysphoria or anything. More like, I’ve always held this image of manhood in my head that I’ve conformed to all my life, and I wonder how much of this image actually feels like it’s me, rather than just something my parents put in.

So I’ve tried wearing dresses and skirts and heels. The dresses I’ve worn felt nice and light, and I loved spinning around while wearing a skirt, but wow was it so hard to walk with heels. I would’ve also tried growing out my hair, but our school had a haircut code, so I didn’t. Then I went to MIT, and my first IAP, I cosplayed as Angeline from Futurama. And I had fun.

Four. Most recently, I’ve been growing my hair out, getting that classic pandemic hairstyle. My last haircut was March last year, and I just… didn’t really bother getting a haircut since then. It wasn’t safe, then it wasn’t that long, then I didn’t have time to, and now I just can’t be bothered.

So my hair’s long now. It’s never been this long, or anywhere near this long. Then I got it bleached, with the help of Zawad. Heck, I might even get it dyed blue.

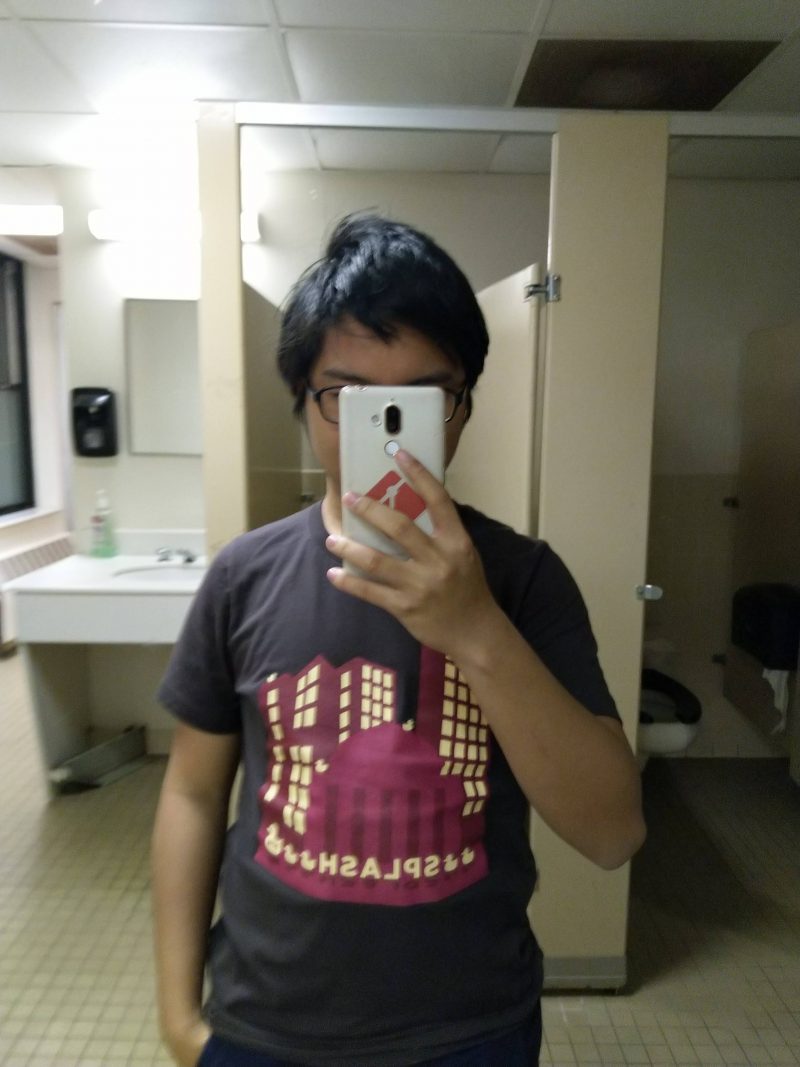

It feels so weird looking at these pictures and going “That’s me. That’s me in the picture. This is a picture of me, and this is what I look like now.” There’s this picture I have of myself in my head, with short hair and a thinner face, like my blogger avatar or my profile picture on Facebook. I liked that image of me.

But then there’s the me that I see in the mirror, with a rounder face, and shoulder-length, half-bleached hair. And this is me now. This is how I actually look. And despite everyone saying that the hair suits me, that the bleached hair looks good, or whatnot, it doesn’t feel like it. When I look at myself in the mirror, I know that it’s me, but often it feels like looking at a different person.

Mirrors must have been very weird when they were first popularized. The only way for you to know what you looked like used to be dim reflections in water, or paintings, which were expensive. There was a time in my life that I lived in a room without a mirror, so I’d go for weeks without seeing what I looked like, and I’d never think about my self-image.

is this selfie aesthetic yet

But today, there’s a huge mirror in the bathroom next door, and I see myself staring back at me on every single Zoom call. Maybe if the only way I knew what I looked like was through what other people said, I wouldn’t feel so bad about myself.