Tangential Learning by Emad T. '14

Isn't the point of research to delve into what you don't know?

More than anything, I’d say that MIT offers a merciless crash course in time management. You’ve got tons of things to do, as well as even more things that you want to do (and learn!), and seemingly not enough time for anything. Fortunately, there’s two periods in which most of your burdens are lifted: IAP, and summer.

That’s why for this summer, I decided to do a UROP involving research that’s tangential to my major…

…and one month later, I learned that a man named Guido van Rossum made Python. (I swear, this will make sense in a few seconds.)

Clearly, van Rossum isn’t your Jersey Shore-variety Guido, so if you’re like me, you might’ve had your mind blown. He’s the type of Guido that made a programming language that I’m now using in my linguistics research.

So basically, even if you’re a Course 9 major (Brain and Cognitive Science), you can still check out research in Course 24-2 (a program in Language and Mind, but this is most often the Linguistics Department) while still being responsible for doing Course 6 (Electrical Engineering and Computer Science) sorts of things. It’s almost like MIT made these fields overlap on purpose.

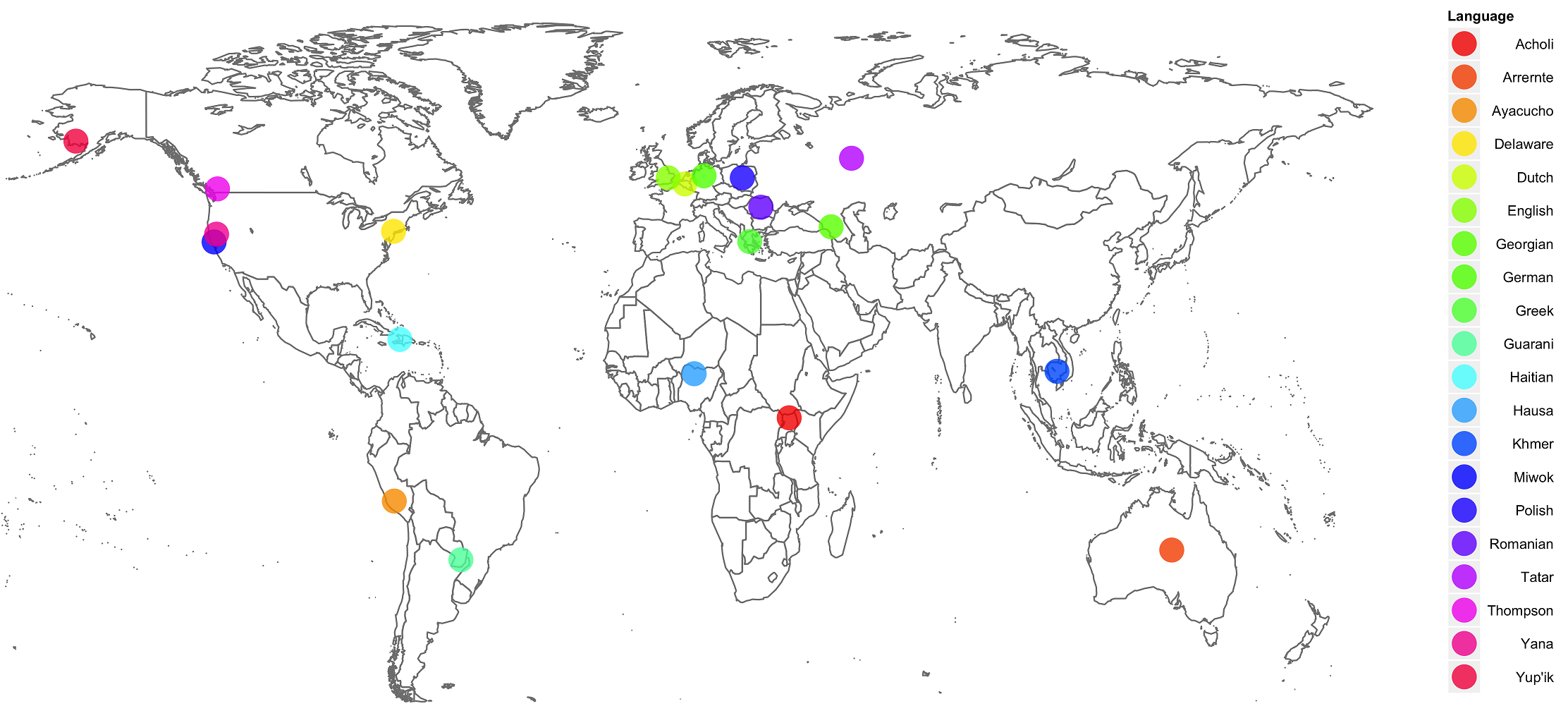

For my UROP, I’m currently working at the Quantitative Research in Linguistics Group, a group that uses large-scale corpus studies to discover constraints on the typology of human language. In particular, our latest project involves putting together a massive phonological corpus that draws on many languages all around the world. How many? Enough to populate a map like this with dozens of colorful dots, one for each language we’ve fully processed so far. (You can make the image bigger by clicking on it)

There are also many sources of data that we have yet to process, like a dictionary of Moroccan Arabic, which I’ve learned has a word for everything as simple as “to be,” to as specific as “a part of a celebration in which a number of men ride horses at great speed and fire long-rifles into the air simultaneously.” The hope is that by analyzing a lot of languages, we’ll see recurring patterns in the distribution of phonemes, or a language’s sound categories capable of making a meaningful distinction. We want to test whether that actually happens, and if so, to what extent those sound patterns of human language facilitate communication between the speaker and the listener.

What surprised me at first is that even though my current career trajectory isn’t headed toward linguistics, I can still do research with a group like QRLG. Such is the nature of the UROP system: if you’re curious about anything at all and can show the knowledge or motivation to be productive, you can find people (and yes, even the funds) to help you explore what you want to research.

And then, perhaps completely by accident, you can end up learning some useful techniques. To be honest, I don’t remember where programming was on the original description for this research project – but a good two weeks in, I found myself getting a refresher on Java, as well as on-the-job training in Javascript and Python.

In true mens et manus style, I quickly took that knowledge and churned out an online artificial language experiment that over 40 people have participated in so far – all without even leaving their house. Once we collect even more data from both the experiment and our corpus, my fellow researchers and I will probably get to work with another language – R, a statistical programming language – in order to do some data analysis. Compared to your typical internship, that’s a pretty sweet deal – not only do you learn about something you want to research, but you can pick up some practical experience along the way.

But the most valuable stuff you get out of a UROP isn’t just the set of skills that you refine or acquire. It’s the very exposure to new things, the chance to explore tangential interests that don’t fit nicely in your four year plan, all under the auspices of someone that wants you to soak it all up. One day, you might be learning about how pidgins and Creole languages form. On a completely different day, you might find yourself fascinated by how someone could design a candy bar that’s tough enough to rip through its plastic packaging, as is the case for Ritter Sport chocolates (of course, that doesn’t have very much to do with linguistics, but I suppose MIT does offer a club for chocolate science).

So if you’ve ever wanted a chance to get some in-depth knowledge of anything – be it your primary academic interest, or just something you’re curious about – a UROP would be a great way to learn about it in a practical environment. We learn by doing at MIT, after all, and nothing is more satisfying (or enlightening) than being right on the bleeding edge of the field.

Welp, that was embarrassing. Fixed

*a group that

I could not agree more to this post!