the journey to PLAYsentations by Michael C. '16

or, the conclusion to the best class I've taken at MIT...so far

There’s a paragraph in Steve Job’s biography where famed Apple industrial designer Jony Ive discusses how his father influenced his early interest in design:

“His Christmas gift to me would be one day of his time in his college workshop, during the Christmas break when no one else was there, helping me make whatever I dreamed up.” The only condition was that Jony had to draw by hand what they planned to make. “I always understood the beauty of things made by hand. I came to realize that what was really important was the care that was put into it. What I really despise is when I sense some carelessness in a product.”

Every Wednesday night for the past few months, from 7 to 10 pm, I’ve thought about that paragraph. Because every time I step into 35-307, I’m reminded of how lucky I am, to have regular access to a 3D printer and a laser cutter and drill presses and countless other tools that young Jony Ive probably never had in his father’s college workshop. To be able to make whatever I dreamed up.

It’s been a whole lot of Christmas since I last wrote about Toy Product Design.

The concept of 2.00b, or Toy Product Design, is fairly simple: break students up into groups of around five, teach them how to use machine shop tools, introduce them to the product engineering process, give them $700, and let them loose. Sounds awesome, right?

Except that I first approached 2.00b with a sense of trepidation. Group projects in high school had never been all that…productive, to say the least. And as a moderate introvert, I was quite familiar with the research about the perils of group dynamics in poorly managed projects. People tend to go with the ideas stated most loudly, rather than the best ideas. Research shows that most brainstorming sessions are a waste of time, because people instinctively mimic others’ opinions and lose sight of their own, succumbing to peer pressure (far more effective is to have people work alone and then later pool their ideas).

2.00b wasn’t free of those group dynamics, of course. But just being aware of the perils of group work made a large difference in navigating those choppy waters. Lessons I’ve gleaned:

- It’s productive to explicitly establish an environment where people can be direct. Be direct when you think something is shoddy, and be willing to take honest criticism when someone thinks your work is shoddy. Don’t settle for an inferior engineering result simply because you’re reluctant to hurt someone’s feelings or because someone else has put a lot of time into something.

- Don’t be afraid to actively take contrary positions to create more discussion, because that leads to a better result.

- Don’t use gyroscopes.

- Seriously, don’t use gyroscopes.

Anyways, where I was I? Oh yeah, ideas. The basic idea behind our product was to create a device that could turn any shoe into a musical instrument. Specifically, a shoe that could take the motions of your foot and generate awesome sounds – your shoe transformed into a beatbox, if you will. We called it Stepper. Partly inspired by Google’s Talking Shoe (shoutout to Zach, from the team who made Talking Shoe, for responding to my emails and giving me some early ideas), and also partly inspired by Google Glass. Hey, wearable technology is all the rage.

An idea’s no good if it’s just stuck in your head, of course. In the first month or so of 2.00b we learned a lot about the prototyping process. A “works like” prototype is often just a proof of concept of technology; a “looks like” prototype should give a sense of what the actual product would look like.

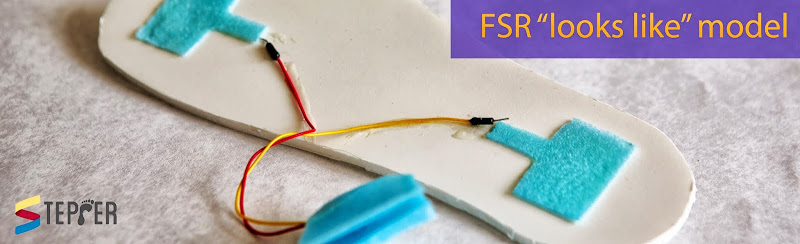

Our initial prototypes used two Force Sensitive Resistors (FSRs) to detect foot taps in different locations:

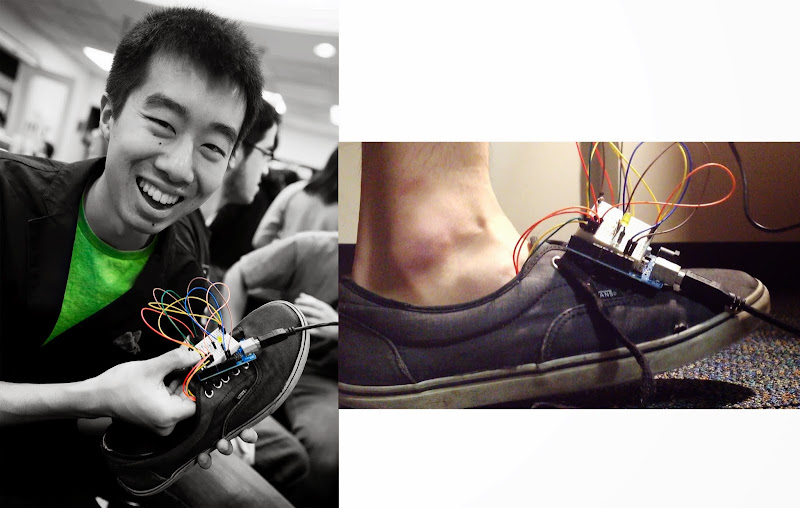

And here is me modeling our first wearable Stepper prototype:

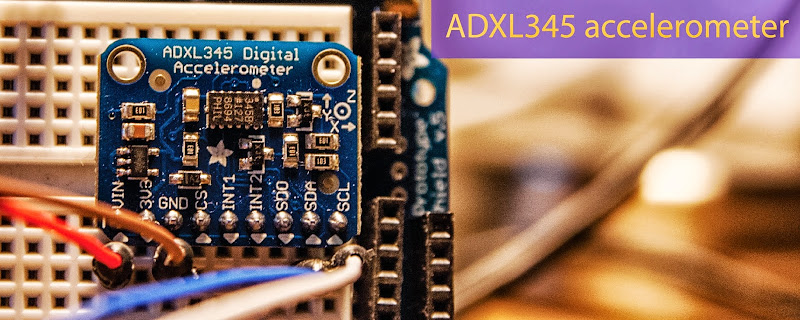

However, we wanted a device that could easily be put on any shoe and transform it into a musical sound-making machine, so FSRs (which required installation underneath the sole insert) were ruled out. We decided to go the accelerometer route; the ADXL345 is a quite advanced 3-axis accelerometer that can detect taps and free fall with some tweaked code, and away we went.

Now we were getting somewhere! The ADXL345 allowed us to detect front and back foot taps with a fair degree of accuracy. But you can’t exactly wear a naked Arduino on your foot. We needed to build an enclosure!

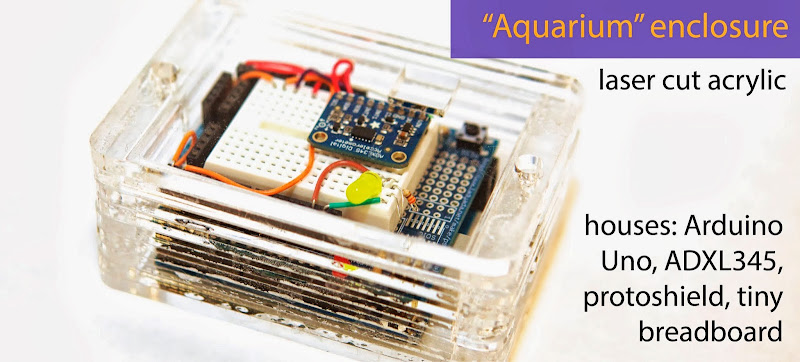

The first enclosure was a very rough job – we just needed it to enclose the gigantic Arduino Uno and protoshield and breadboard. I nicknamed it the Aquarium.

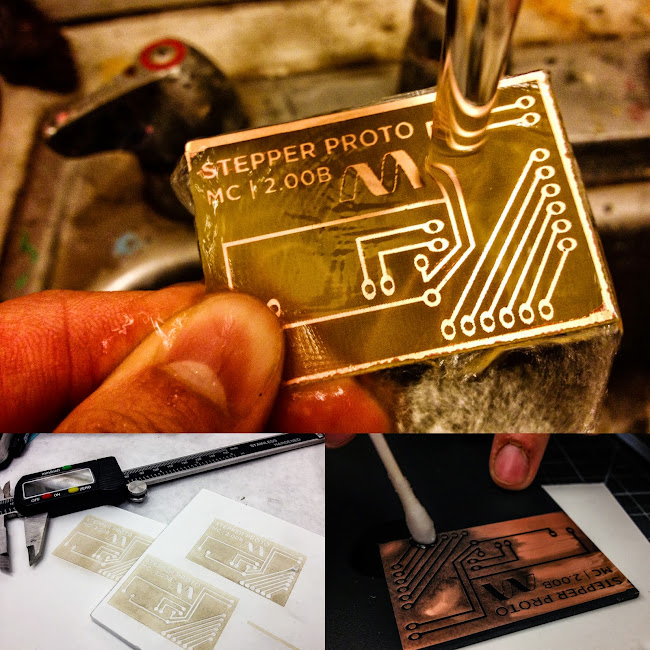

To miniaturize Stepper, I learned how to etch a copper circuit board:

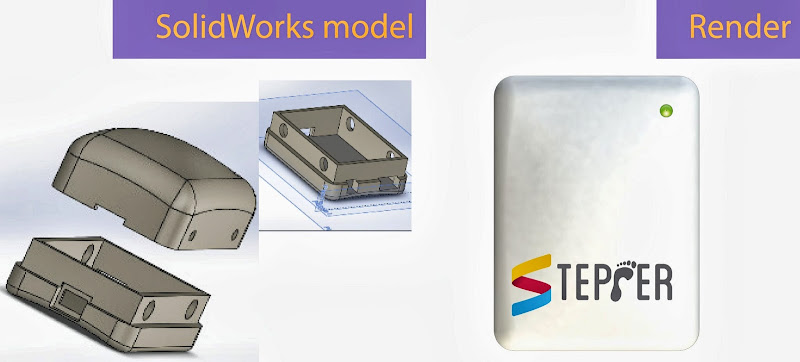

And once we miniaturized Stepper, we could start thinking about smaller case designs:

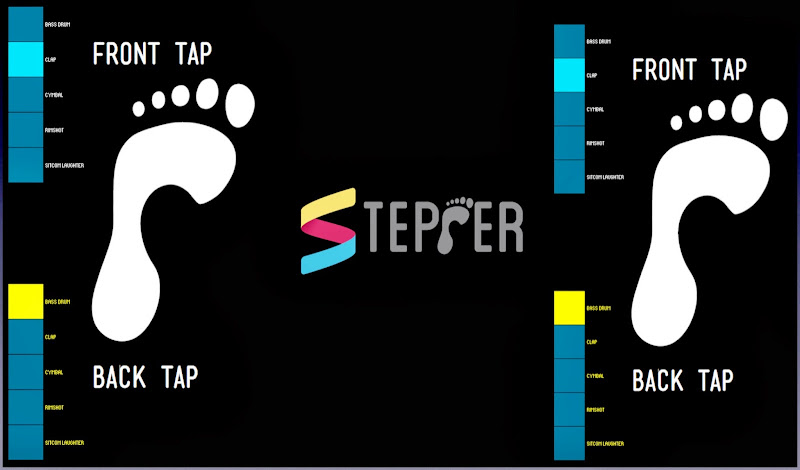

How about software? Literally 3 days before Playsentations, I decided that I wanted to create my own software for Stepper – namely, software that (1) let you easily pick and choose your own sounds for Stepper to play, and (2) let you visualize your steps in real time. So I learned a bit of Processing (which is really just Java) and made this:

Blue/yellow circles will flash on the foot in the appropriate location when front/back taps are triggered. Sounds can be picked from the blue and yellow boxes, and audio files can be easily imported.

Not the prettiest program, but hey, not a bad result for learning Processing three days before our final product was due.

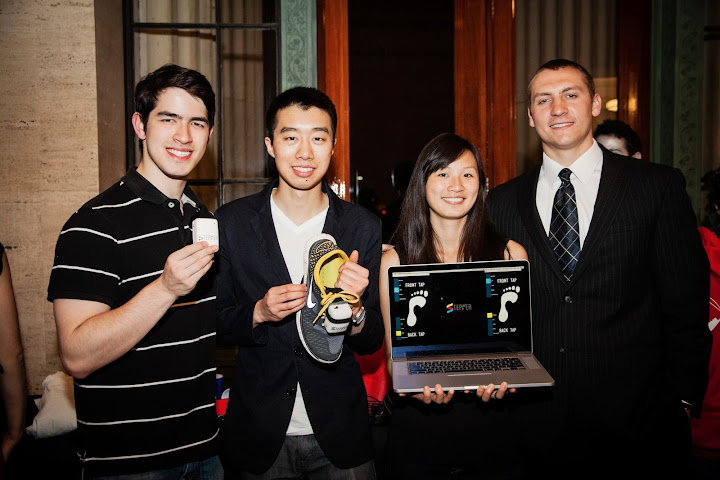

And finally…it was time for PLAYsentations! In one of MIT’s largest lecture halls (10-250), each team gave a five minute presentation/skit, with a few minutes after for Q&A. It was tons of fun. I tried to do my best Macklemore impression. I failed.

Other teams also had awesome playsentations:

And then there were group photos.

The culmination of a semester’s work. It felt good!

Photo credits to Geoff Tsai, Steve Keating, Bo Yu, Qifang Bao, Connie Liu ’16, and Michael C. ’16 (that’s me!)