Three patterns from the pattern language of my life by Natasha B. '16

Hello! It’s about 3,000 days since I graduated from MIT, and three weeks since an even more significant phase change of life, involving a newborn.

In the 3,000 days, I moved to Washington, D.C. (for a fellowship writing for CityLab, then part of The Atlantic), moved to New Mexico to be near my family, worked as an architectural researcher and urban planner for five years, reconnected with a friend I met on the first day of CPW and married him, and moved across the Atlantic to the other Cambridge to research city-scale planning for shallow geothermal energy and ground source heat pumps.

In the three weeks, I have mostly just snuggled and fed and changed my baby, grabbed scraps of sleep when possible, and eaten the nice food people have brought to me. Life with a small baby is rich in patterns and scant on plans. A pattern, in the canonical architecture and planning guidebook A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein,

describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.

The problems: hunger, discomfort, an onslaught of stimulation from the world outside the womb. The solutions: milk, a change, patting, rocking, sleep. Solutions given or applied a million times over, never exactly the same way twice.

Because 3,000 days is a much longer time than three weeks, with a greater variety of patterns, problems, solutions, and events, I’ll account for the eight-plus years since I last blogged in a format inspired by A Pattern Language. A Pattern Language presents all elements or patterns, whether “sacred sites,” “pools and streams,” or “nine percent parking,” in roughly the same format. Each is laid out in this way:

“First, there is a picture, which shows an archetypal example of that pattern. Second, after the picture, each pattern has an introductory paragraph, which sets the context for the pattern, by explaining how it helps to complete certain larger patterns.” Then three diamonds marking the beginning of the problem; after the diamonds a headline, in bold type; then the body of the problem, including “the empirical background of the pattern, the evidence for its validity, the range of different ways the pattern can be manifested in a building,” and then the solution: “the heart of the pattern–which describes the field of physical and social relationship which are required to solve the stated problem, in the stated context.” The solution is given in the form of an instruction, and often accompanied by a pleasing little squiggly diagram or two. Each pattern chapter concludes with a paragraph outlining its links to the smaller patterns in the language, just as it began with a paragraph linking it to the larger patterns earlier in the book.

So here are some patterns excerpted from the unwritten idiosyncratic commonplace book of my own last decade. Remember, this is personal and made up! The “solutions” are written as instructions addressed to me, not to the world at large as they are in the real book. If you don’t relate, you can make your own imaginary book, your own preliminary pattern language.

Courtyards

…within a site containing one or more BUILDINGS (11), a courtyard may provide a kind of OUTDOOR ROOM (163) that is both private and shared. The courtyard may act as a CEREMONIAL SITE (171) or a LEISURE SPACE (183) for picnicking or sunbathing. In exceptionally good weather, the kinds of activities that normally take place indoors may relocate to the courtyard.

❖ ❖ ❖

An outdoor space that is open to the sky but enclosed on the sides can be lifeless and blank, or it can be the liveliest part of a site–it depends who is there, where their paths cross through it, and how the ceremony is done.

I graduated in Killian Court in 2016. I don’t remember walking across the stage, but I remember holding up my diploma and smiling while my mother took a photo, opening the diploma book when my sister said “show the diploma!” and looking on in horror five seconds later as a big splotch of bird poop landed on the creamy white cardstock near my name. I remember this because the green splotch is still there, and also because the whole sequence was photographed. Nature keeps me humble.

There’s also a photograph from that day of me and Justin together, which his mother must have taken. We were good friends throughout college (here he is in my blog post from 2014), but hadn’t seen each other much senior year, when we both lived off campus in opposite directions. After graduation, we fell out of touch for a few years until one day he messaged me, and on a whim I invited him to visit me in New Mexico, and he came. That was that, pretty much. Eleven months later we got married in a courtyard of the house my family was living in at the time. Extremely fun. My friend Eden wrote this song as a gift in honor of the day. That courtyard, in a house where some stranger lives now, was the most beautiful one I’ve been in. Sun-baked stucco walls enclosed a rectangle, with heavy wooden doors in the northwest and southeast corners. On the northern wall was a mural that might have been ninety years old, like the house. In the center were a small green octagonal pool with a bubbling fountain and a heavy-limbed apricot tree. Yellow roses bordered the edge of the courtyard by the house, and at the opposite end, a few steps rose up to a small sort of stage, where we had the ceremony. The only bad thing about the courtyard was a stupid little novelty plaque on the far wall that said “on this site in 1897 nothing happened,” which is obviously untrue. Things are always happening.

After the wedding, we moved to Albuquerque, to a funny house shaped like a ‘U.’ The bowl of the U made a kind of informal courtyard, surrounded by the white sides of the house and by the crumbling adobe brick wall that separated us from the gravel road. We set up an outdoor dining table and a pottery wheel in the shade of big elm trees, and when it wasn’t too blistering hot or freezing cold (Albuquerque is a land of extremes) we spent days out there, and sat around with friends in the afternoon.

Cambridge, England, where I am now, is full of courtyards. I have never been in a city with more courtyards per capita, or more grass tennis courts. I’m not saying it’s an efficient use of space, especially considering that many of them are off limits to foot traffic, and are only there to provide a green and well groomed carpet for the empty air above them. I do love the tennis, though. Being a PhD student after years of working and living outside academia is a little like stepping off a public street into a quiet courtyard. The institution around me provides some insulation from the commercial and professional pressures outside, giving me time and space to think hard and slowly and undertake deeper research than I could when I was working a regular job. I want to make the most of it. I’m also aware there is some loss inherent to being too cloistered, and some risk involved in loitering too long in a courtyard, without walking into the buildings around you, or venturing out into the next wider open space. Courtyards are meant to be crossed.

The entry on courtyards in A Pattern Language is titled not just ‘Courtyards,’ but ‘Courtyards Which Live.” A courtyard can be a perfect gathering place for celebration, or airy room for special pieces of communal life, but to be really alive it must be connected, opening onto a larger area and linked with the intimacy and comfort of the interior spaces adjacent to it.

Therefore:

If you are in a courtyard, physical or metaphorical, be alive. Pay attention to the people there with you, and keep continuity with the larger world and the interior spaces around you.

If you’re lucky enough to have access to a small, pretty courtyard at home or nearby, sit out there and have your coffee as often as possible, and try to keep the plants alive if they’re your responsibility.

Cocoons

…this pattern provides a respite from the larger patterns of FORWARD MOTION (12) and PUBLIC LIFE (3), nests within SEASONAL FLUCTUATION (17) and HOME (20), and relates to RESTING PLACES (31) and MAINTENANCE (14). Periods of life spent in the COCOON pattern are defined by retreat from outward-facing activities and external achievement and reward, and may be marked by partial employment, introspection, and the absence of frenzy. A good COCOON may not look or feel generative at the time one is in it, but provides a supportive environment for recovery and transformation.

❖ ❖ ❖

At times, it can be helpful to withdraw from regular activity, adopt a slower pace or even step backward, and cocoon.

In 2020, I had a frustrating, stagnating job and family chaos was burning me out. Meanwhile, the pandemic. My husband I moved to Albuquerque and nested hard–planted beans, peppers, and tomatoes, set up eleven chickens in the squat straw-bale coop in the backyard, and rapidly collected an overabundance of Craigslist furniture (later, we saw sense and pared it down). Two of my best friends came to live with us the summer of 2020, and in that period of pre-vaccine uncertainty and social distance, we were lucky to have a house that was lively and safe. When fall came, I quit the job, intending to take a new job I had been offered, but when it came time to commit, I had a strong feeling that the new job was not in fact what I wanted. I took some time to figure out what to do next. I had about a year of underemployment, intermittent freelance projects, spiraling, unspiraling, and planning. I applied to grad programs and started working at a landscape architecture and planning firm I really liked. The year felt long, and I was unsure and sometimes afraid, but in retrospect, it was in some ways a golden time, a rare extended pause. Our house was full of light and barely insulated. For the winter, my husband sewed me a literal cocoon in the form of a housecoat made out of a duvet.

The slowdown came to an end as my work ramped up and we prepared for the transatlantic move. Our lives since 2022 have been the opposite of contained. The geographic spread, the juggling of my research and writing jobs and Justin’s work and work travel, and the decision to have a baby now rather than waiting have contributed to a welcome level of complexity that is also sometimes difficult. But now, right now, I’m in another little cocoon. My focus on my baby and meeting her needs blurs out everything around us most of the time. I am typing with my right hand only, because my left arm is holding a warm, soft, sleeping weight.

This won’t last too long, and I believe that ultimately raising a child will expand my life and connections to the world, not contract them. Cocoons are designed to be temporary structures. Two quotes stuck in my head during my pregnancy. One is from James Baldwin, from the potent and historically resonant essay “Notes on the House of Bondage.”

The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.

The other is from the narrator of the novel Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih.

Everyone starts at the beginning of the road, and the world is an endless state of childhood.

Therefore:

Appreciate the cocoon while you’re in it. The road is wide and long, you’re still near the beginning, your child is at the very very beginning and will exist beyond you into an unfamiliar future. Her world is in its infancy. Our world as a whole is characterized by unremitting change, steady undercurrents and rapids driving movement beneath the surface, and breaks are necessary. To take a break, or make a good cocoon, hunker down in a place as simple and secure as you can find and turn your attention inward. Limit striving, or restrict its range to a single area. Be easy. Make the walls of the cocoon soft and flexible, not too strong. It’s just a seasonal dwelling.

❖ ❖ ❖

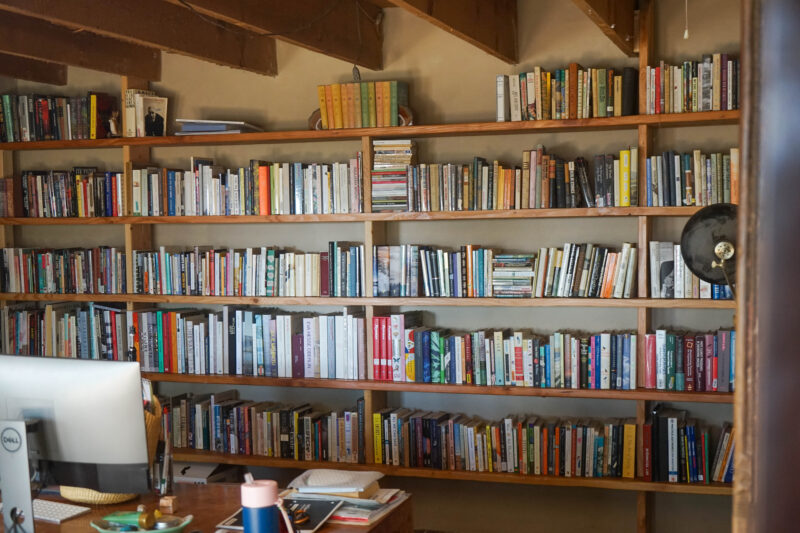

Periods of cocooning are supported by NAP TIME (91), COFFEE AND TEA (100). Immersion in public or personal LIBRARIES (46) may enrich the quality of time spent in the cocoon. SITES SUITABLE FOR SCHEMING AND DAYDREAMING (66) should be identified and fully utilized.

Blogs and Letters

…this pattern fulfills the blogger’s need to write and publish. It relates to the larger patterns of LEARNING (7), PUBLIC LIFE (3), and PLACES FOR CONVERSATION (18).

❖ ❖ ❖

I need to write.

You can take the girl out of MIT, but you can’t take the admissions blogger out of the girl. I’m no longer sitting at a booth in Steam Café at the top of Building 7 filling up notebooks in between classes (and have learned from yesterday’s alum blog posts that Steam no longer exists?), but I’m still a scribbler.

I’m a frequent guest author for the wonderful newsletter Scope of Work. Scope of Work is broadly a platform for writing about the physical world, and a community of people interested in and working in engineering, manufacturing, and infrastructure. My most recent installment, one of my favorites, was about soda ash, the Solvay Process, and the history of glassmaking.

Before I started writing for Scope of Work, I had a newsletter about buildings, materials, land use, and climate change called Buildingshed. I wrote about stone construction and the architecture in The Age of Innocence, Adrienne Rich’s “Powers of Recuperation” and Mariame Kamara’s work in Niger, and my part-adobe house. Eventually, I let the project lapse, but I have vague and occasional plans to revive it in some way, so if you’re interested, you can subscribe and you may get an email someday.

We’re in newsletter boom times, which is great, but I also miss old-fashioned blogs like these. Ursula K. Le Guin blogged. Lebbeus Woods blogged. I’m compelled by Mandy Brown’s argument for publishing your work on your own site:

A website is, among other things, a container. The shape of that container both constrains and makes possible what goes within it. This is, I think, one of the primary justifications for having your own website. Not just so you can own your stuff (for some meaning of “ownership,” in a culture in which any billionaire can scrape your work without permission and copyright only protects the rich). Not just so you have a home base among the shifting winds of the various platforms, which rise and fall like brush before the fire. Not just so you can avoid setting up camp in a Nazi bar. But also so that you can shape the work—so that you can give shape to it, and in that shaping make possible work that couldn’t arise elsewhere.

Therefore:

I’m going to start a blog, and it will live on my website.

❖ ❖ ❖

BLOGS AND LETTERS are fed by READING (40) and relate to the downstream patterns of NOTEBOOK KEEPING (173), CHATS (180) and DOCUMENTATION (171).

Love**,

Natasha

** Patterns marked with the double asterisk in APL are labeled ‘true invariants.” “In these two-asterisk cases we believe, in short,” the authors write, “that it is not possible to solve the stated problem properly, without shaping the environment in one way or another according to the pattern that we have given–and that, in these cases, the pattern describes a deep and inescapable property of a well-formed environment.”