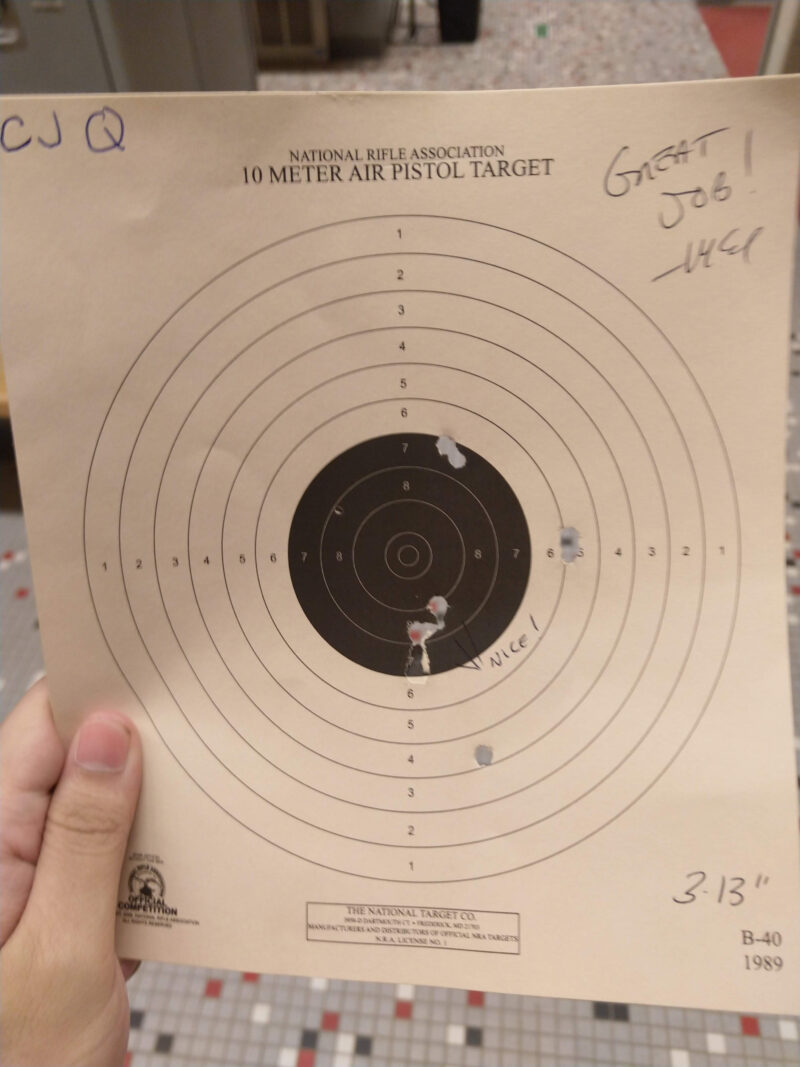

Targets by CJ Q. '23

shooting things and hitting them

Sport air pistol, the PE class I took this quarter, was taught by instructor Mike Conti. Of the ten years he’s taught shooting at MIT, this is the first semester he’s teaching air pistol.

The class begins its meetings in the ready room, a room next to the shooting range itself.

On the first day of class, we talk about the goals for the class, safety, and talk about the air pistol itself. The aim is to learn to shoot precisely, and the air pistol is pretty much made for that. The trigger is light, there’s virtually no recoil or vibration, the lock time is quick, and it’s quiet enough to shoot without needing ear protection.

The class is nine days long, and on the eighth day of the class, there’d be a short competition, when we’d have ten minutes to discharge six shots into a paper target ten meters away. The shots would form a group on the target, and we’d be judged not on how close our shots are to the center, but on how tight the group is. So the aim was to shoot the same way, every single time, as consistently as possible. He called it Top Gun, and there was even a trophy and everything.

On the second day of class, we talk about the mechanics of shooting with the pistol. We talked about loading the pistol and charging it with air. The pistol had to be loaded one pellet at a time. Not only was this a limitation of the pistol itself, but it was a general rule for precision shooting events that weapons be loaded one pellet at a time.

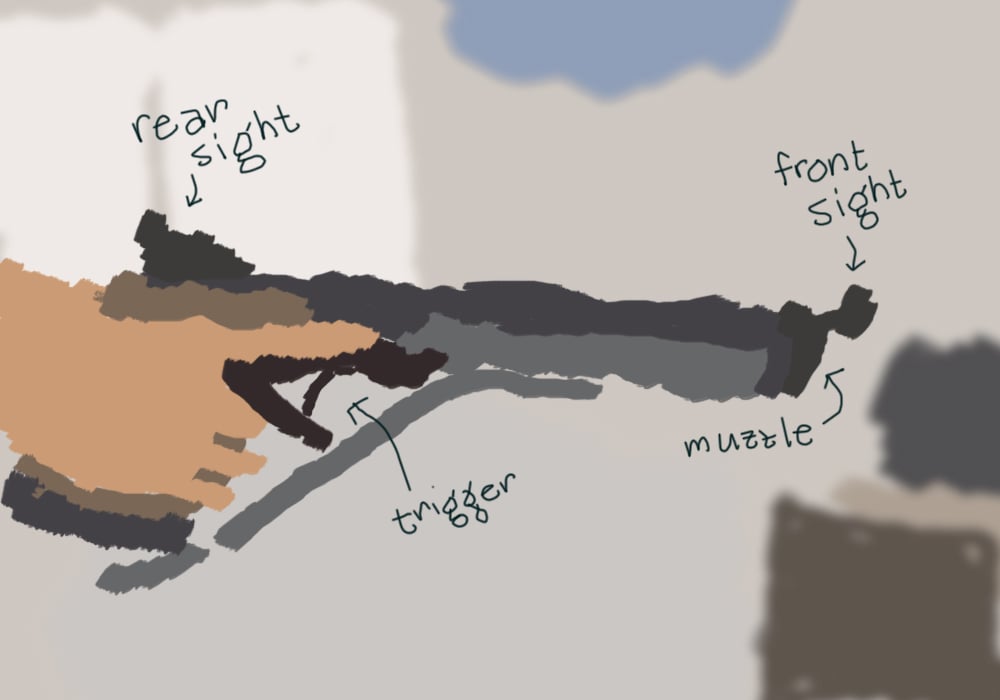

We talked about the parts of the pistol. There was the muzzle, the part where the pellet shoots from. It was good practice to always keep the muzzle pointed at a safe direction. In the range, that direction is downrange, toward the target. Toward the ceiling is generally safe. There was the trigger, of course, where you press your finger in order to shoot a pellet; another part of safety was to keep your finger off-trigger until the moment you actually have to shoot. These were things I was at least vaguely aware of before class.

What I was not aware of was the existence of the sights. There is a rear sight, above the grip of the pistol, which is shaped like a U. Then there’s a front sight, a black rectangle, above the muzzle. To aim the pistol, you needed to align the sights with the target, and the sights with each other.

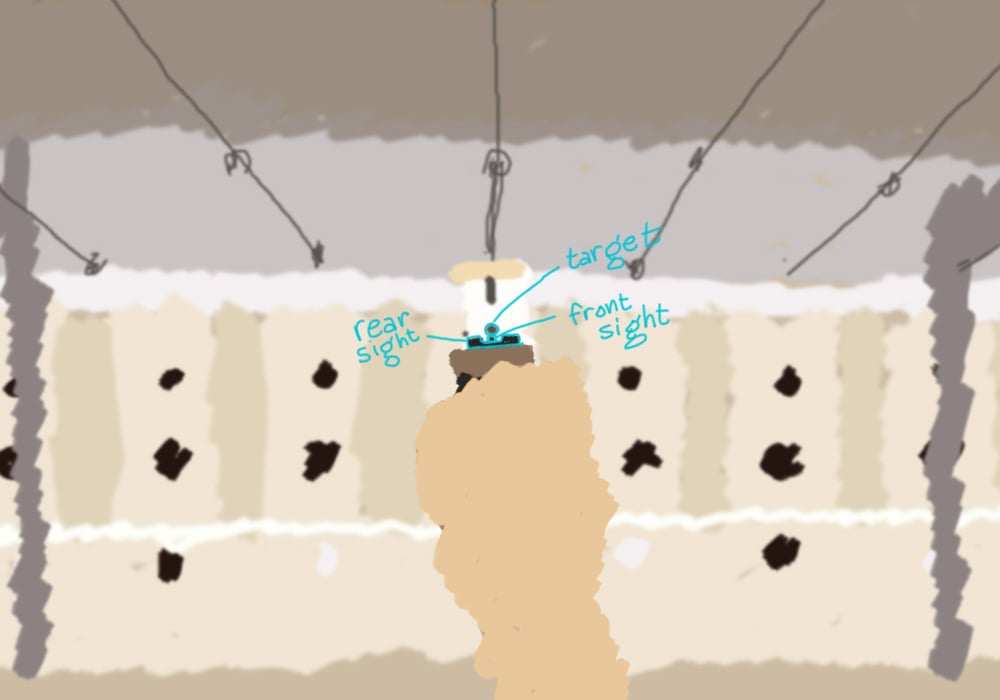

The emergency exit of the ready room had a paper target that instructor Conti used to demonstrate sight alignment and sight picture. These were the same paper targets that we’d be shooting on.

He had this black plastic tool to show what the sights looked like when aligned.

Sight alignment is about getting the sights aligned with each other. The front sight should be vertically aligned with the rear sight, which means that the top edges of the sights should be on the same height. It should also be horizontally aligned, which means that there should be an equal amount of space to the left and right of the front sight. Hence the mantra: equal height, equal light.

Sight target is aligning the sights with the target itself. A popular way is the six o’clock position, which means positioning the sights such that the target rests directly on top of the front sight.

To check sight target, the eyes shouldn’t be focused on the target, but on the front sight, and the eyes should remain focused on the front sight. The rear sight and the target will look blurred, and this is fine. Even after discharging the shot, the focus should still remain on the front sight, for a few moments, before lowering the pistol in a controlled manner, and only then should you look at the target. Hence the other mantra: front sight, front sight, front sight.

It seemed simple in principle. Close one eye, bring the pistol up to your vision, align the sights with each other, align the sights with the target, and shoot. And do it the same way each time.

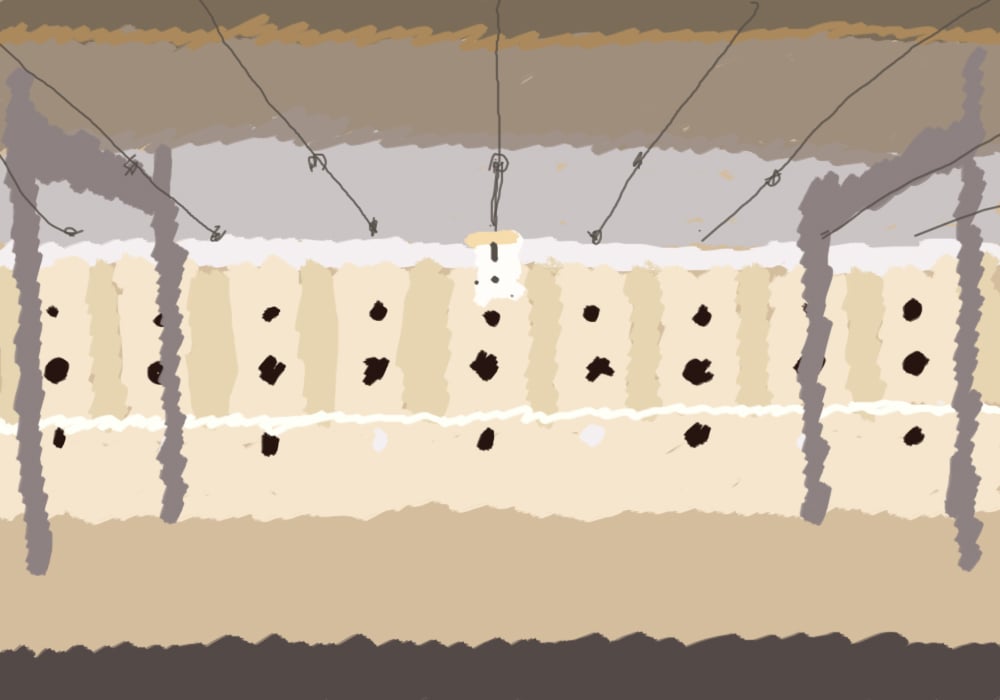

On the third day of class we went to the range to shoot for the first time.

The range had fourteen stations, and for social distancing reasons, only five of the stations were used for the class. Each station had its own metal backplate that we clipped paper targets onto. The backplates were hung from a wire that we reeled to send the target downrange. The target locked position at the ten meter line.

We shot from a benchrest position, which meant that we shot from a seated position, with the pistol resting on a sandbag.

In practice, the sights were way smaller than what the demonstrations made them look like.

The rear sight was short, even stubby. The target was but a tiny speck in the distance. Imagine, say, the diameter of a pen held at arm’s length. The target was even smaller than that. The front sight was an even tinier rectangle, that moved wildly with even the slightest twitches.

Worse, everything was blurred. Yeah, sure, I knew that the rear sight and target would look slightly blurred; that much is a consequence of focusing on the front sight. Front sight, front sight, front sight. But really, it felt like everything was blurred. I guess it was then that I understood why this was hard. It felt like I had to shoot on faith.

I took a deep breath, aligned the sights as best as I could, and then let the breath out. Then I took another breath in, tried to clear my mind, focused on executing the shot as cleanly as possible. My finger pushes on the trigger. It feels like it barely even traveled before I hear the pellet fire, all while I hold my focus on the front sight.

I waited a few heartbeats before looking up from the sights, and looking at the target. I couldn’t make out where the shot fired at all, which, I guess, makes sense. The target was probably a hundred times larger than the hole the pellet would have made, and the target alone was a speck from this distance.

We were told to reload, and then to shoot again when we were ready.

After a few shots, we reeled our targets back in, and instructor Conti visited each of our stations to look at them. It was only when the targets were reeled in that I could see how I did during shooting. Maybe that’s a good thing, that I only knew how well I did after it was all over.

That day, the third day of class, was the first time I shot any kind of gun at any kind of target. It wasn’t a target I was proud of.

Air pistol is a mental, almost meditative sport. Once you got the motions down, a large part was concentrating on your breathing, keeping your body as still as possible, and clearing your mind of distractions.

After the fourth day of class, I learned what a bad shot felt like. It feels like everything’s going fine, but when the moment you press the trigger, you feel that one thing that’s slightly off. By the time you realize, the shot’s fired, and it’s too late to correct it.

That day, I felt it. There was that one, bad shot in the middle of firing. And I tried to breathe, and remember what instructor Conti said. Let it go. The next shot will be perfect.

When we reeled our targets in, and I had that one hole on the target far away from any of the other holes, instructor Conti asked me if I knew which shot that was. I said it was the sixth shot. He asked me what was wrong, and I told him that my arm felt tired. He told me to learn from that shot, reminded me I had five good shots before that, and then told me to forget about it.

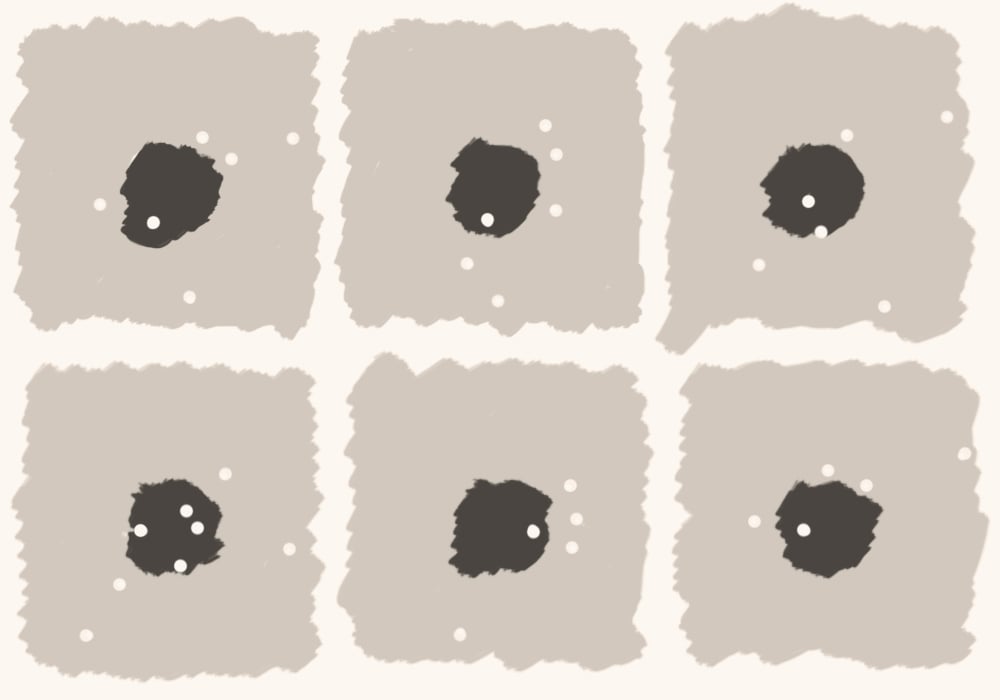

The shot groups on a target tell a story in and of itself. When my shots were everywhere, that was when my mind was everywhere too. When my shots were good, that was when I felt calm and focused.

Sometimes, there would be a nice, tight group, except for one shot, far away from that group. Remember, Top Gun was judged by the farthest pair of shots. It doesn’t matter how close the rest of the shots were, if there was that one heartbreaker shot that’s far away from the group.

That shot tells a story not just of what I was thinking about when that shot was fired. It tells a story of what happened afterward, when I reeled the target in to look at the pattern of my shots on the target. You don’t need to be there to guess how it made me feel to see so many holes bunched up with each other, and then having that one shot far away, messing up the group.

But I couldn’t let it get to me. I tried to detach my emotions from my performance as much as I could. The next one will be better. The next one will be better.

We were told that the targets were ours to decide whether to keep or dispose of. After the third day of class, I told myself that I would only keep a target I was proud of shooting, because that’s how I want to remember the class. So I threw away the targets I shot that day.

On the fourth day of class we shot standing, now, with a two-handed grip. Again, my shots were pretty good, except for that one shot that was off because I lapsed in concentration. I threw away the targets I shot that day.

On the fifth day of class we shot with a one-handed grip. This felt way, way harder for me than a two-handed grip, because I didn’t feel like a single hand could support the whole weight of the pistol. As expected, my hand moved around a lot, and my shots were everywhere. I threw away the targets I shot that day.

On the sixth day of class we had drills where we shot from a one-handed grip, then a two-handed grip, then a one-handed grip again. My two-handed grip shots felt way better. I felt like I could actually control the movement of the pistol, without shaking too much. My one-handed grip shots were okay. They weren’t everywhere anymore, but they were still way less consistent than my two-handed grip.

Top Gun is a one-handed shooting competition, and I kinda wanted to do well. So I needed to get better shooting one-handed. And I threw away the targets I shot that day.

On the seventh day of class we had free range to shoot thirty-five pellets however we wanted, for pretty much the whole class time. We could grab new targets whenever we wanted, shoot in whatever stance we wanted to, try things out, whatever.

I tried shooting a target one-handed. It was awful. Worse than the previous day, even worse than the first day we shot one-handed. Instructor Conti came by to ask me how I was doing. I said I was fine, just a little tired.

He suggested I try shooting from benchrest, which I did for my next target. That felt better. Still not a target I was proud of, but it was better.

Then I shot one-handed again. A little worse than the previous target, but it was the best out of any of the one-handed targets I’ve shot. And that felt good. I felt like I’d improved a lot, and I was feeling good about shooting for Top Gun.

The last target I shot that day, I shot two-handed. Even if it was two-handed, I was still shaking from the fatigue.

Remember how I said that it feels like I had to shoot on faith? That feeling never went away. It’s not as if my vision got any clearer. But I did feel steadier, calmer. As if I had something thicker to rest that faith on.

I made an excellent shot group. It was tight. All together. Not the tightest group I’ve ever made, but all my previous tight groups had one or two shots far away from the group. This was slightly larger, but at least it was consistent. Eight shots, all around the same area.

I kept that target. That was the first target I kept from class.

On the eighth day of class was the actual competition: Top Gun. Now, obviously, my performance here didn’t really matter; I was going to pass the class all the same. But who didn’t want a shiny trophy and a neat certificate? Six shots, ten minutes, one-handed.

Warmup didn’t look good. My shots were everywhere, and I could feel it; something was off. Each time I reeled in the target it felt bad, bad, bad. The instructor checks in with me, and I say it’ll be alright. It’ll be alright. The next one will be better.

Ten minutes is so long, especially when you only have six shots to make. I was tense, and nervous, and I tried my best to not look at anyone else’s targets and focus on shot after shot. After each one, I rested my arm for what felt like forever, and I still had lots of time remaining at the end.

I felt pretty good how I did. When we reeled our targets in, and I finally got a good look at my target, I thought I did pretty well.

Was it the best target I’ve ever made? No. But it was better than any of my warmup targets that day, and maybe that’s what matters.

Instructor Conti looks at the target, tells me I did a good job. I take the target off the metal backboard, write my name, and submit it.

In the beginning of the next class, which was our last class together, the winner of Top Gun was announced. I didn’t win. Not by far; I was third in our class of five.

Our Top Gun targets were returned to us. After class, I threw mine away.