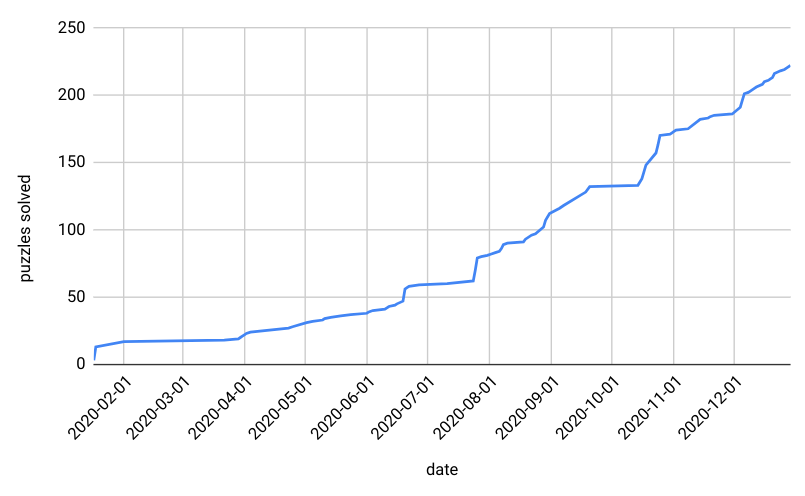

Two hundred puzzles, fifty weeks later by CJ Q. '23

a post of galactic proportions

This post contains spoilers for the theme and structure of MIT Mystery Hunt 2021, which are unmarked. This post will contain spoilers for some puzzles, which will be marked.

Organizing this post was a pain, because the experience of writing a hunt involves so many different things that I’d imagine different people are interested in. In the end, I decided that I’m just going to write about everything I’m interested in. Which is everything, including all the dry details that’ll be boring to anyone but me. I’m granting you the permission to skip every section that looks like it won’t be interesting.

Most of what I’ll be writing about is what others contributed to the Hunt, and I will strive to assign credit where it’s due. But I’ll probably neglect several things and overemphasize others, especially parts that I contributed to more.

Thanks to ✈✈✈ Galactic Trendsetters ✈✈✈ for reading and giving comments on drafts of this incredibly long post, and Alan for editing.

- So your team won the Mystery Hunt

- How to write a puzzlehunt

- From the new world

- Why is everyone on a video call?

- Becoming stronger

- Mystery Hunt, Mystery Hunt!

- Heart and soul

So your team won the Mystery Hunt

What is a puzzlehunt?

First off. I made a post about last year’s Hunt, which also has an explanation of what a puzzlehunt is, so you can look at that. But the tl;dr is that a puzzlehunt is an event where teams compete to solve a series of puzzles. Each puzzle solves to an answer, which is typically some English word or phrase. Here are some puzzles from this year’s hunt that I think are good introductions:

- Don’t Let Me Down, the puzzle in this year’s hunt that got the most solves.

- At A Loss For Words, a cute minimalist puzzle.

- Relitasti, a charmingly illustrated puzzle about pasta.

- Lime Sand Season, one of the puzzles written last-minute but still ended up being very well-loved.

- ✏️✉️➡️3️⃣5️⃣1️⃣➖6️⃣6️⃣6️⃣➖6️⃣6️⃣5️⃣5️⃣, a puzzle where you had to send text messages to the phone number in the title, a good example of “literally anything could be a puzzle”.

There’s also the excellent DP Puzzlehunt, a puzzlehunt aimed at beginners that introduces a lot of puzzlehunt tropes. Puzzlehunts have become more and more accessible since the last post I wrote, so it’s a great time to start puzzling!

Of course, puzzlehunts aren’t just about the puzzles. In my previous post I strived to present puzzlehunts as a very human phenomenon, emphasizing not just the puzzles, but the story and art and production value, the relationships between the people in a team, and the relationships between teams. And after spending a year writing for the hunt, I think it’s all the more true that puzzlehunts aren’t just about puzzles, and I hope this post will outline the reasons why.

Finally, this is probably the best time to talk about all my favorite puzzles before your attention span disappears, so I’ll just list them here, in the order they appear in the All Puzzles page: ✏️✉️➡️3️⃣5️⃣1️⃣➖6️⃣6️⃣6️⃣➖6️⃣6️⃣5️⃣5️⃣, Enter the Perpendicular Universe, Exactly, Over 9,000: an Abbreviated Yet Awesome Tour Of Your First Equally Excellent Puzzle Mechanic, Simmons Hall, MacGregor House, Student Center, Love at 150 km/h, Successively More Abundant in Verbiage, So You Think You Can Count?, Squee Squee, Baseball, 100…00116, Circular Reasoning, PClueRS, Nutraumatic, Enclosures, Bingo.

Top-level organization

Last year, I hunted with ✈✈✈ Galactic Trendsetters ✈✈✈. We solved a bunch of puzzles. We found the coin, and won the Mystery Hunt. Then what?

Immediately after the wrap-up, people started a Discord server for people who would help write the 2021 hunt. We used Discord for organizing our work for the 2020 hunt, and supposedly Galactic has been using Discord for the past four years or something, so it was the obvious choice. Discord is also excellent for having great search features and having an archive of all the messages, which was an incredibly useful reference for writing this post.

Not everyone in the winning team ends up writing with them, so the team often splinters into a separate group for a year before merging again the next year. So I was quickly faced with the decision of whether or not I wanted to write for the next hunt. I realized that I probably wouldn’t get another chance like this for the rest of my undergrad, so I jumped on it.

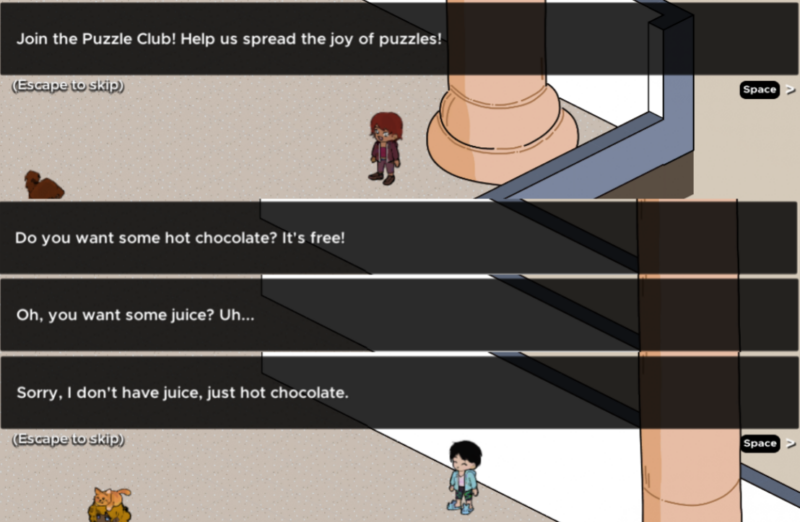

Then there were the meetings. Galactic writes a yearly puzzlehunt called, aptly, the Galactic Puzzle Hunt, and the GPH team needed to decide what was going to happen with that. They decided not to run GPH 2020. Some of the members of Galactic had a meeting with some of the members of Left Out to talk about transitional things: sharing documents, survey results, talking about the timeline, logistics, stuff like that. There was also a meeting with the MIT Puzzle Club, the student organization in charge of liaising between the writing team and MIT.

The first team-wide meeting was two Mondays after the hunt ended, so the last Monday of January. In the kickoff meeting we began elections for the Benevolent Dictator, discussed some of the proposed hunt design goals, talked about the theme proposal process, and sketched out the creation schedule. The purpose of the BD is to direct the flow of hunt design, and have the final say in the decision process, hence the “dictator” part. But the BD is also benevolent, which is why the BD would lead the team through voting and committee forming and other such decisions. Plus, BD is a cooler name than president.

We elected Jakob and Josh01 Breaking admissions blog convention here; many of the people I mention are MIT alumni but several aren't, and I also don't know everyone's years off the top of my head, so I just won't write years. as our BDs, and then the theme proposal committee was formed through some process I don’t quite remember. It might just have been “whoever volunteered”.

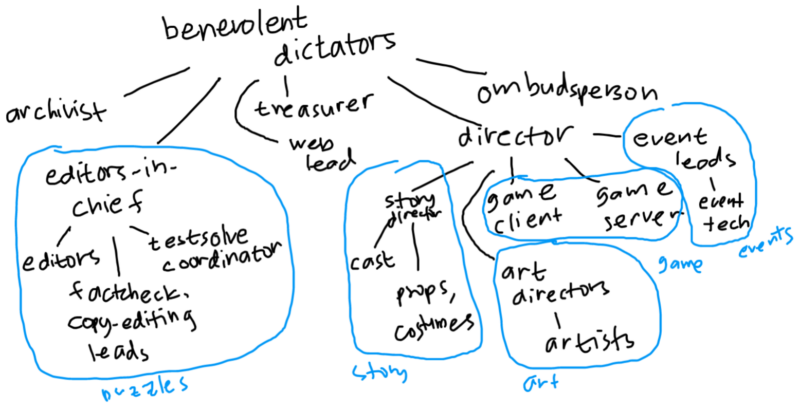

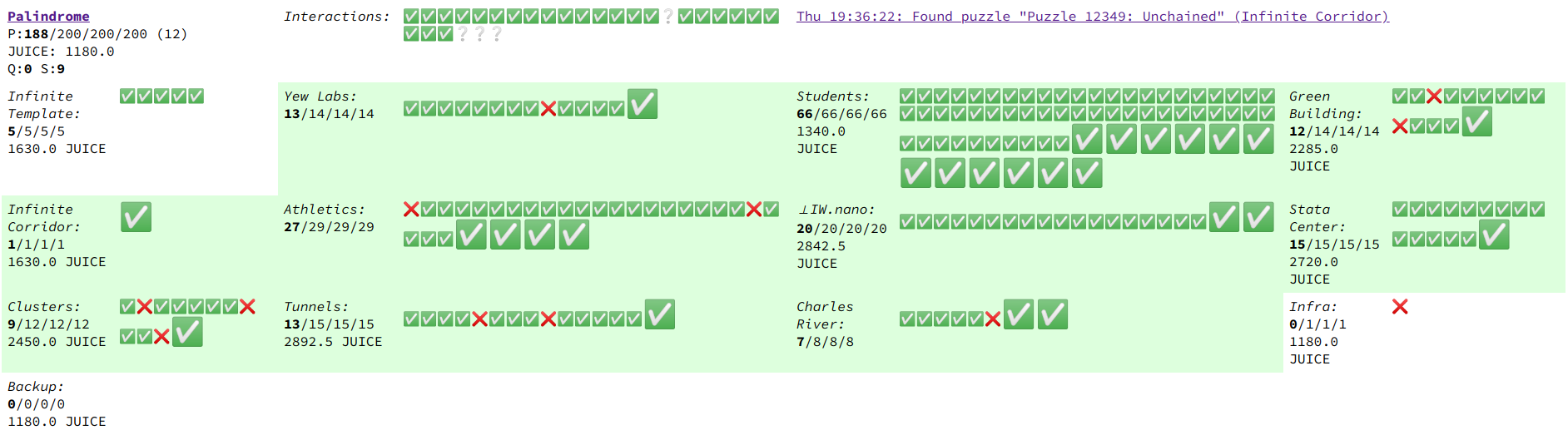

Below the BDs are the exec team. There’s the editors-in-chief, who are in charge of leading puzzle writing and editing. There’s a director, in charge of things like the story, interactions, and keeping the pulse on hunt experience. Then there’s a archivist, treasurer, and ombudsperson, which sound exactly like they sound like. After we decided the theme, we elected the exec team. This happened on the last week of February; you can view the elected exec on the hunt credits page.

And then there are the various subdirectors, which were appointed, not elected. We had directors for art, story, and events, which are what they sound like, all kinda under the director. We had our website tech lead, who was, yes, in charge of the website. And because the theme we selected involved programming an entire MMO, we also had a game server lead. Again, these are all in the hunt credits page.

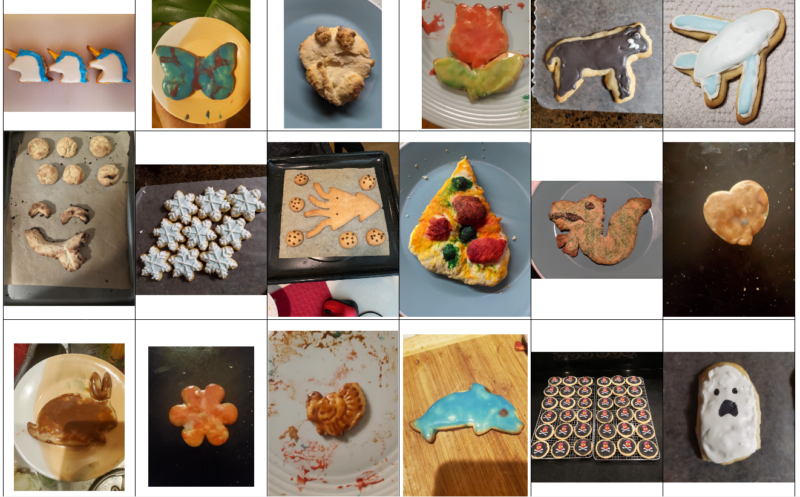

yay paint

The overall structure is thus kinda sorta shallow? A lot of power is vested in individual groups and people to make decisions, with democratic votes only being done in things like electing the exec positions, theme selection, and some major logistical decisions that were made later. Again, the whole group contributes to decision-making, but the final say rests with relatively fewer people.

I guess the only real thing I can compare this to is ESP, and in that sense it’s actually pretty similar. ESP has its exec roles, and then it has the program directors, and then there are the subdirectors, and subdirectors are given the freedom to make their part of the program their own. I’m not sure how other organizations feel like.

One last thing that I wanted to mention is that we had exec meetings on Monday nights, beginning in late March. At first they was every two weeks, and by December they was every week. The exec meetings were a chance for all of the subgroups to give their own reports about their progress, so it was a nice way to hear about how all the different parts of the hunt were going. In that sense they were kinda like ESP meetings.

Design goals

One of the first things discussed was the hunt’s overall design goals. It might seem that there’s not much point to this, which was what I thought at first: doesn’t everyone agree what a good hunt looks like? Well, even good hunts vary in several parameters: some are aimed at smaller or larger teams, some are a few hours long while others last weeks. Even within the bounds of an MIT Mystery Hunt, which has a pretty set format of “weekend-long, two hundred or so puzzles, has scavenger hunt and events and interaction and story”, there’s still lots of room for variation. And even then, there’s also the question of which goals are more important than others.

A survey was sent out before our first meeting soliciting what people wanted the goals for the hunt to be. The two biggest responses were to give a satisfying experience for all teams, not just top ones, and to innovate02 Original phrasing being TRENDSET the Mystery Hunt. within the bounds of the hunt. The second goal here is actually kinda notable; taking a risk writing our first Mystery Hunt wasn’t a straightforward decision. It was something people wanted nonetheless.

After the meeting, a goals committee was formed to write a design goals document outlining our “mission statement”, in a sense. If memory serves, this was formed once again from “whoever volunteered”. They had a meeting and wrote up an excellent document listing some philosophical goals and target metrics.

“Fun for all teams” ended up being the first listed goal, and I think for good reason. Catering to teams of all sizes and skill levels sounds like something that should be obvious, but being intentional about it helped a lot in theme proposal and initial decisions. Many of the proposals had a demarcated intro round or mid-hunt runaround, meant to be satisfying milestones for teams of different sizes. Another subgoal that emerged from this goal was to “have a good hint system”.

I think we had some ambitious metrics for this one. For example, we wanted 10 teams to finish the hunt this year, which to me felt like a big number, since last year it felt like only two or three teams finished it. We also wanted 20 teams to reach the hunt midpoint, and 50 teams to have some sort of interaction. To help achieve this goal, we aimed for the coin to be found on Sunday morning, but to keep hints and interactions going until Monday morning, if possible.

The other big philosophical goal was balancing innovation, quality, and workload. GPH is known for being innovative in the sense of having ambitious themes, interesting structures, and non-traditional, interactive puzzles. We wanted to bring some of that to the Mystery Hunt, and have it throughout all the parts of the hunt, so that it’d be seen by teams of all sizes. But we didn’t want to compromise on the quality, and we also wanted to keep the hunt writing experience fun for us.

Some other design goals that don’t fit within these two big ones. We wanted to leave the hunt finances and puzzlewriting tools in a better place than where they started. We wanted to be willing to delay unlocking metas. We didn’t want final puzzles to be difficult or aha-based. We also wanted to support remote teams where possible, which, given what happened this year, was one of the goals we definitely achieved…

Creation schedule

One of the things we touched on in the kickoff meeting was the overarching timeline to get the hunt written. We selected by the end of February, exec and subdirectors were picked by March, most metas were written by mid-May, three “Big Test Solves” happened in August, October, and December, and all puzzles were testsolved by the beginning of December.

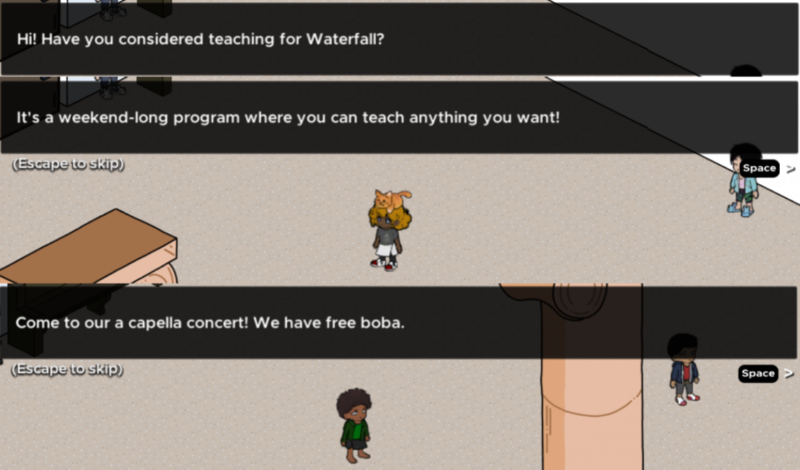

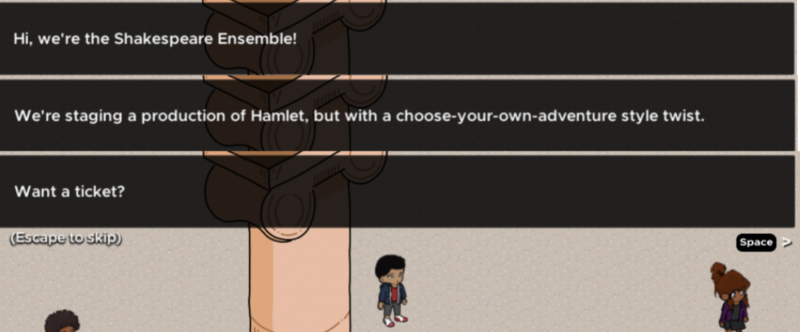

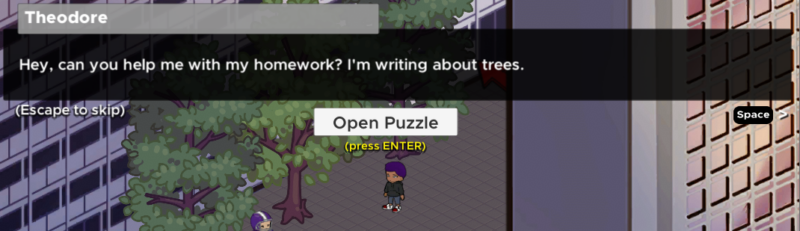

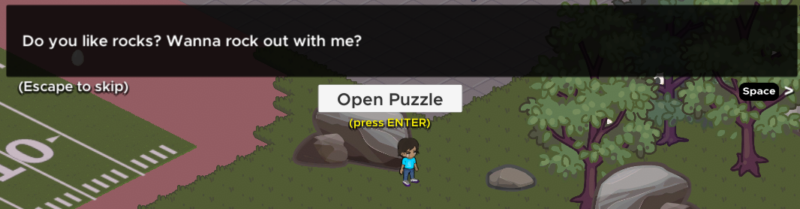

The theme we selected involved creating an entire virtual world of MIT’s campus, where the rounds would be buildings. Selecting the theme brought its own set of deadlines to the table. I’ll touch more on the timeline of this virtual world, the MMO, later. Roughly, it was released for testing in May, and we also used the MMO during each of the Big Test Solves to find puzzles.

Of course, COVID happened. We had been thinking about it since March, and a COVID committee was formed in July to make decisions about what was going to happen to the hunt. The final decision was made in August, after plenty of surveys and discussions about the choices.

There were a handful of times we fell behind schedule, but it turned out fine in the end, since the schedule was designed to accommodate some slack anyway. This is another thing I learned from ESP: always include some amount of slack in the timeline, even if you think you won’t need it. It’s a rare occurrence when a program we run doesn’t have to adjust one deadline or another.

Theme proposal and selection

We talked a little about the theme proposal process in the kickoff meeting, and it took us most of February to choose a final theme. We had dozens of theme ideas in the days after hunt ended, and to help narrow them down, we required proposals to have a proposal document. This document consisted of the theme’s title, a short pitch for the theme, a description of its plot and rounds, reasons to pick that theme over other themes, and some risk analysis.

Each proposal had a small set of authors. Although anyone could contribute to a proposal, each person could only be the author of at most one proposal. People who weren’t proposal authors could be part of the theme proposal committee, which helped authors make revisions in their proposal. Then the proposals would be cut to a shortlist of at most five proposals by approval vote, these proposals would be developed even more, and then there’d be a final vote for the theme.

The proposals that weren’t selected have to remain secret, but I can give numbers. We had nine proposals by early February, which were cut to three by February 12. After another week to develop the three proposals, we had a meeting on February 24 where the authors presented their themes and anyone could ask questions about them. The final theme was selected on February 26 through STAR voting.

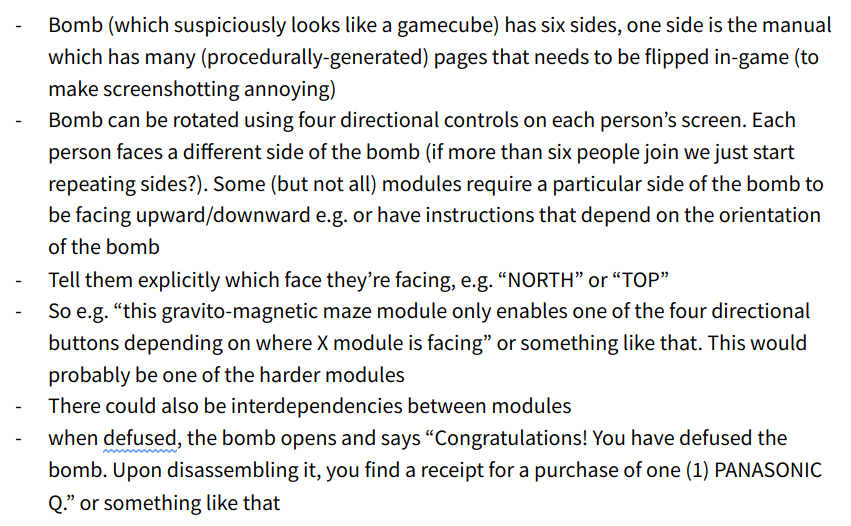

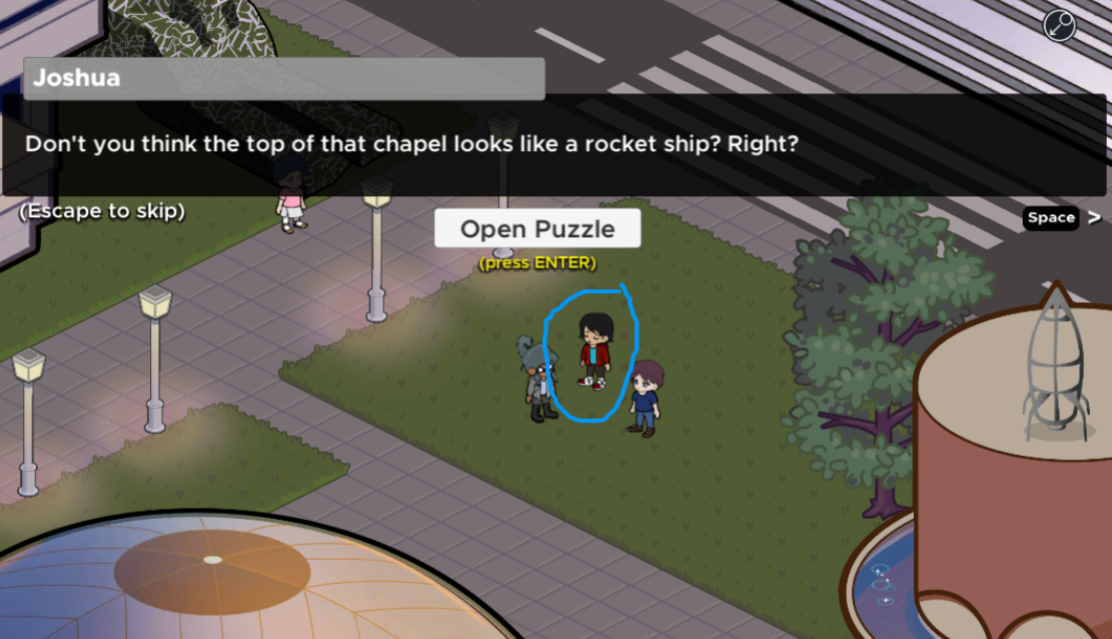

So yes, we knew very early on that the hunt would have a virtual MIT—in fact, the original proposal called for it, describing it as a “persistent, multiplayer online server”. The theme became known as the MMO theme, and we’d refer to it internally as “the MMO” for pretty much the rest of the year.

People got passionate about the theme proposal process. I’ve seen thousands of words, concept art, demos, even metas, all written for themes that ultimately did not make the cut. The contributors for each proposal became an informal subgroup, holding meetings to workshop and refine ideas. I myself became pretty passionate about a theme that didn’t make it past the approval voting phase, so I could definitely understand that feeling.

There was a lot of discussion about the pros and cons of selecting each theme, which at times felt pretty intense. Consider the MMO theme, for example. The work involved in making the MMO and the risk of technical issues was a topic people argued about many times. Lots and lots of pages were written about the MMO during the theme selection process.

I was afraid that the theme selection process alone would cause hurt feelings within Galactic. But in the end, people argued hard, the MMO theme was selected, and then we all came together and wrote a Mystery Hunt. Which was kinda nice, I guess. Strong opinions, weakly held.

The original theme proposal

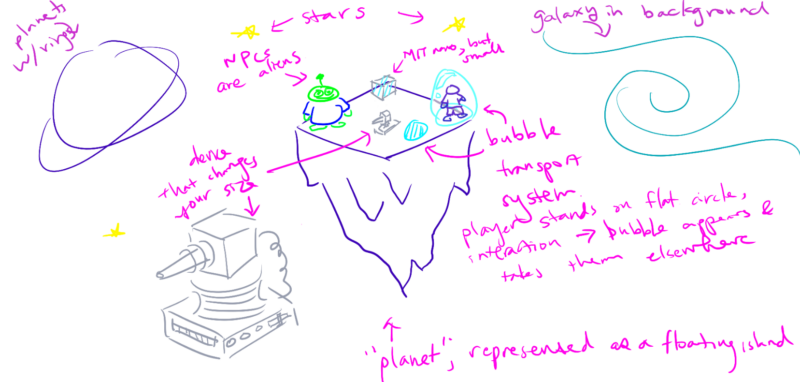

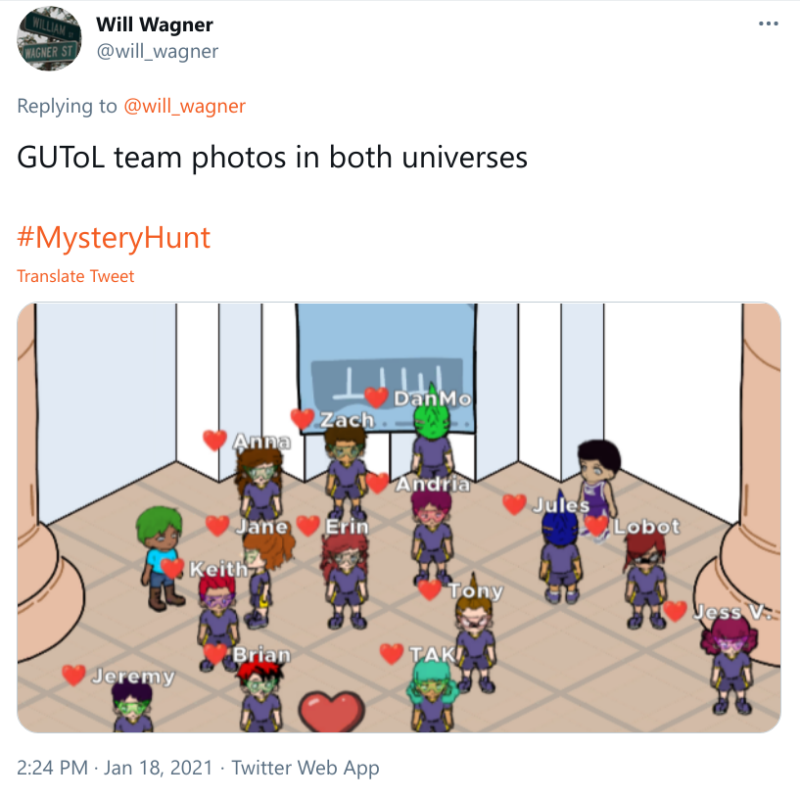

The MMO proposal was titled “From the New World”. One of the core authors on the theme, Nathan, wrote a post about Hunt, including a lot of thoughts about the theme, and it’s really good and you should read it. But here are some of my thoughts about it:

- A lot of the story is pretty much unchanged from the original proposal. For example, consider names. The name Barbara S. Yew was in the original proposal. Robin was originally Dr. Robin Octree rather than Robin Vogel. J Linden was called True J,03 True J lives on as the name of one of our Discord bots. One of True J's responsibilities, for example, is rebuilding the MMO. and Professor Hemlock was known as Professor Fusion. Originally, Professor Fusion was an impostor Yew rather than a separate person.

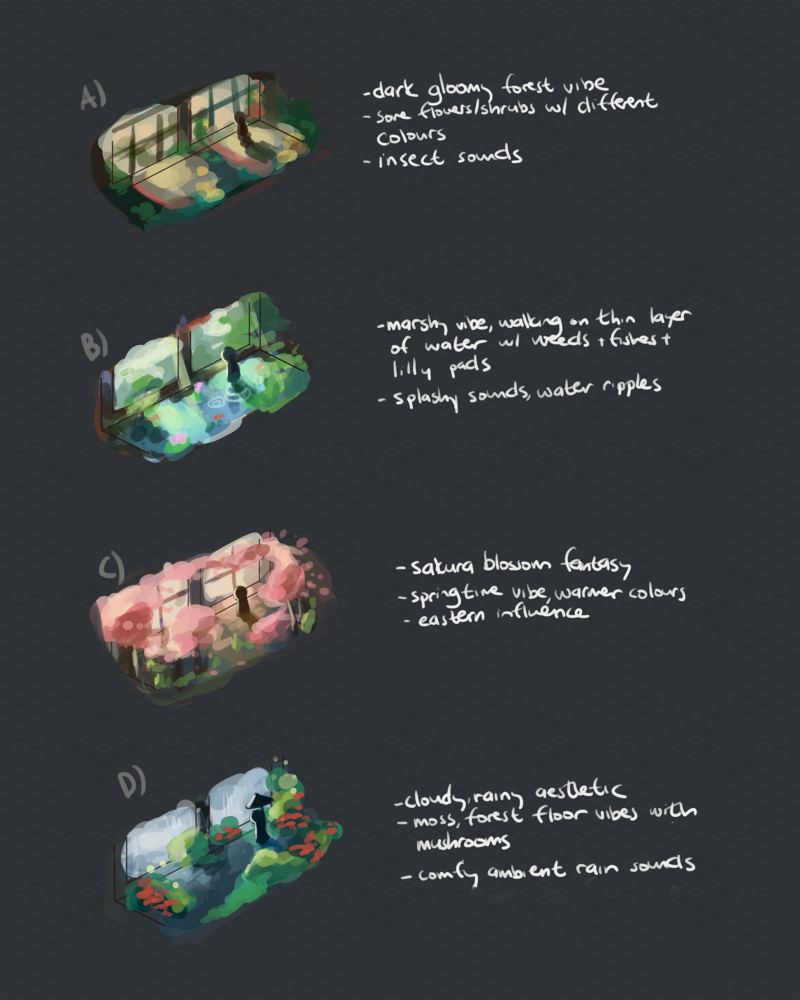

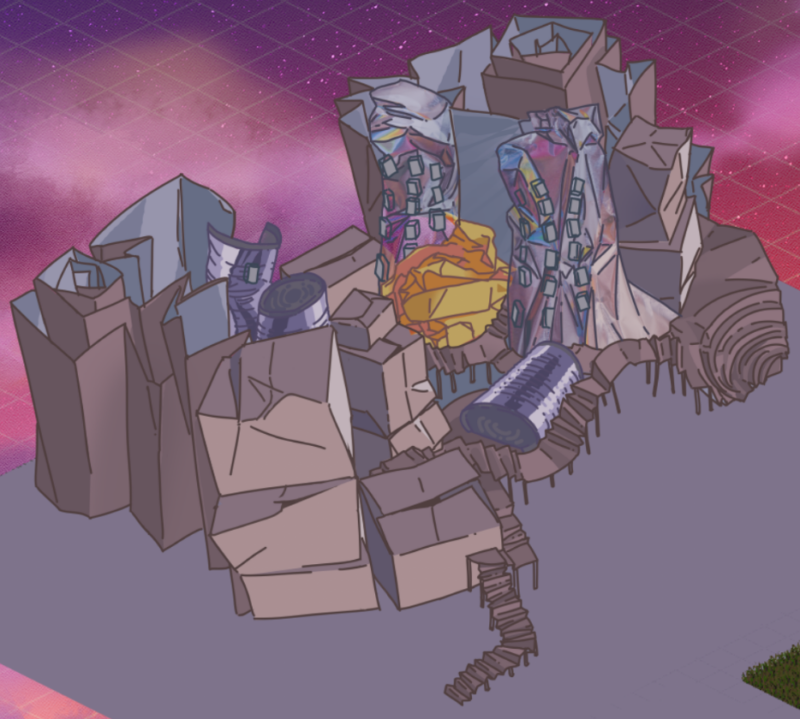

- The broad strokes of the story were also the same: Professor Yew gets stuck in the other universe. Teams fix a device in the intro round to access the MMO. Power is restored to the portal to bring Professor Yew back, except Professor Fusion comes back instead. Both professors are returned to their original universes and there’s a final search to find the coin. Things would be transferred between universes using a portal. Here’s some early concept art from Lillian.

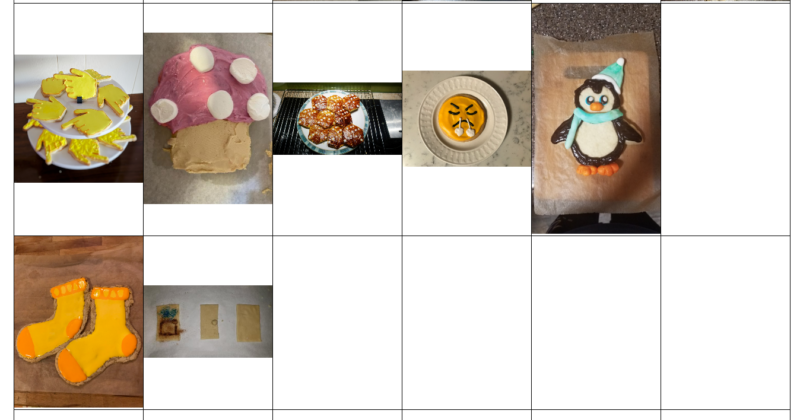

watercolor! water-based marker drawing!

- Probably the biggest difference from the original proposal was cutting runarounds. There was supposed to be an intro runaround to assemble the “dimensional device”, then a mid-hunt runaround to power the portal that sends Professor Fusion through. Both were cut. The original proposal also called for the hunt midpoint to happen after fixing certain rounds, but this was eventually changed to just be a timed event.

- The final runaround of the original proposal was also pretty much kept, although it did go through several revisions before ending up there, which I’ll talk about later. But the original version goes like this. Professor Yew used a coin in the alternate universe in a vending machine to get a cup of coffee. After recovering the coin, it warps and enlarges. Professor Yew then attempts to use it in a vending machine, fails, and then gives it to the team as a memento. As our actors didn’t have access to campus, that last part had to be cut, but the plan always was for the coin to be a mundane, normal coin.

- The details of the MMO and how it interacted with puzzles were all in the proposal, and were all mostly unchanged. Several of the rounds were also in the original proposal. I won’t go into this too much, but I think this shows how thoroughly the proposers thought about the MMO when they proposed it.

How to write a puzzlehunt

Life cycle of a Mystery Hunt

After the theme was decided, the metas could be written. A metapuzzle is something like the capstone puzzle of a round; it uses all the puzzles in the round as “feeder” answers, and these answers are used as inputs to the metapuzzle to produce another answer. Typically a Mystery Hunt is structured such that once you finish the meta for a given round, then your team is done for the round, and once your team solves all the metas you initiate the endgame. Their importance means that metas tend to be constrained by the theme, and they need to be anchored to the plot as a whole.

A puzzlehunt’s structure, then, means that it needs to be written backwards. The metas get written, and these give the answers for the puzzles. Then the puzzles are written to solve to the given answers.

Our meta writing process consisted of a bunch of brainstorming sessions to get an overall sense of what the hunt would look like. All of the metas had Jon and Rahul, our two editors-in-chief, assigned as editors. The EiCs were the ones in charge of helping develop the ideas and getting the metas testsolved. They also had the more global role of keeping the total number of rounds and puzzles reasonable.

Metas tend to be blockers to a team’s progress, so they needed thorough testsolving to make sure they had the right difficulty. The rule of thumb is that a metapuzzle should be solvable with around three-fourths of a round’s answers, and not solvable with much less than that. To simulate how solving metas would work in the hunt, testers were given some number of answers, and they could ask for more answers every once in a while.

All of our metas got three to four successful testsolves, and to my knowledge all of them were revised several times in the process. Once the EiCs were satisfied with the meta, its answers were then released, so puzzles could now be written for these answers.

The meta writing process began in March, after the MMO theme was selected. The initial goal was to get all answers released by mid-May. This didn’t quite happen, as it turns out. Most of the answers were released by then, but the Tunnels answers were released in June, and the Athletics answers were released in September.04 Apparently they could've been released earlier, but the delay was for deciding whether or not to include the round in the first place, since there were concerns about hunt being too long.

Puzzles got written throughout the whole year, with the important deadline being that all puzzles were finalized by the beginning of December. This didn’t quite happen, although almost all of our puzzles were testsolved by then.

Some puzzle-related decisions

Beginning with August through December, other puzzle-related things needed decisions: how answers would be called in, the hint system, and the rate at which puzzles are unlocked.

For Mystery Hunt, the fact that they’re called answer call-ins tells about their history. It used to be the case that a team would call HQ, state their team name, the puzzle, and the answer, and then HQ would confirm whether or not their answer was right. By 2010, possibly earlier, it changed to a queuing system. Teams would use the website to put their phone number in the queue, and then HQ would call them and ask them to spell the answer, letter by letter.

Even later, answer call-ins became answer callbacks. The team would submit the answer on the website, and then a few minutes later someone in HQ would call them and confirm whether or not their answer was right. Last year, the Left Out decided to switch to automated answer checking, in which teams simply typed in the answer on the website and got instant confirmation of whether they were right or wrong. People had mixed reactions about this; see this blog post and its comments for some discussion.

Galactic had its own discussion about whether or not to keep answer checking, and we made the decision to keep it. We then needed to make the decision about lockout. After all, we didn’t want teams to guess every word in the dictionary. Left Out had their own lockout algorithm. Our policy ended up being more forgiving than theirs:05 I'm informed that this was intended to be stricter, but I don't think this is true. three incorrect guesses in a round locks out submissions for five minutes, but each puzzle has two free guesses that don’t count towards that limit.

Then we needed to decide what the hint system would be. For the hint system itself, we decided to copy Left Out’s system. Teams could have one hint request open at a time, but could otherwise request freeform hints for any puzzle they’d unlocked hints for. Hints were unlocked for a puzzle once thirty teams had solved it and after some amount of time had passed since the team unlocked the puzzle. Freeform hints are the best for getting teams unstuck, but it also meant answering hints took some effort on our part. GPH has found that having canned hints, or pre-written hints that hint-givers could edit, helped save time answering hints.

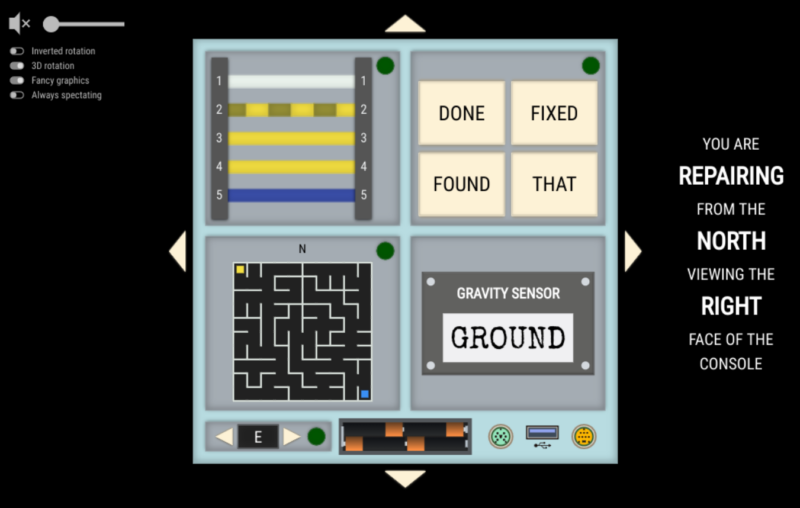

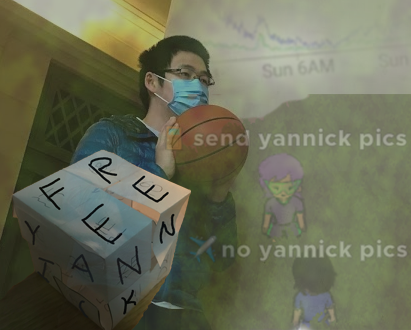

And then there was figuring out the rate of puzzle unlocks. This mostly involved modeling how teams would solve puzzles, which is inherently difficult to predict. Our editors, mostly Jon, Rob, and Yannick, had several spreadsheets, a Python simulation, and even a machine learning model, to get the numbers right. The final details06 Boring numbers incoming. ended up being something that, in my opinion, was pretty elegant.

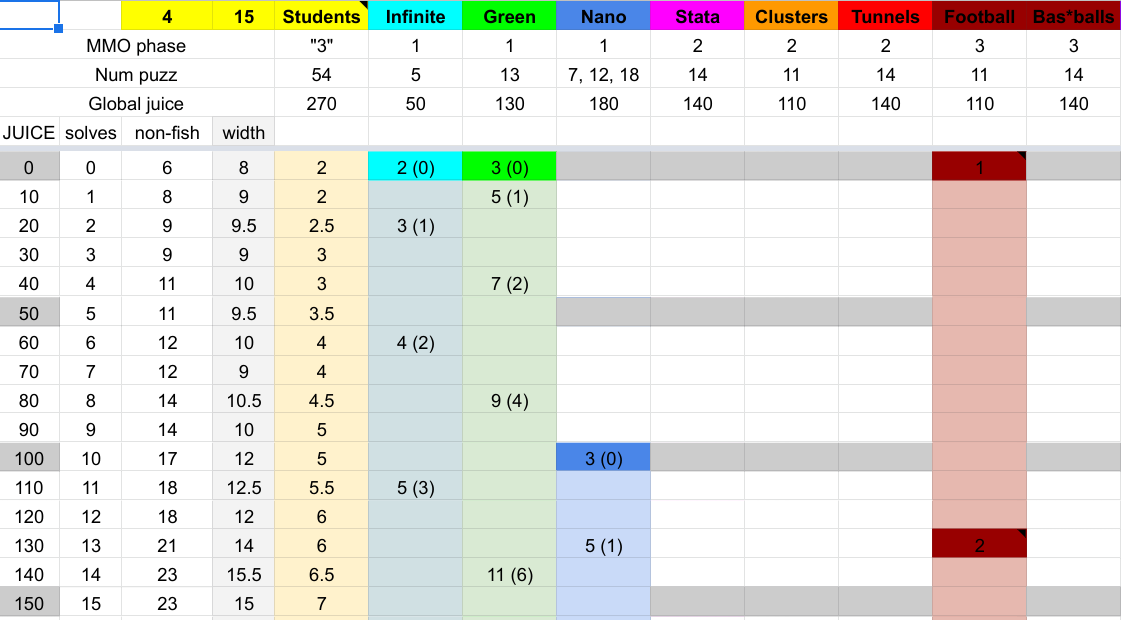

The intro round, Yew Labs, had its own unlocking schedule: four puzzles unlocked initially, then solving a puzzle unlocked approximately one more. For all other rounds, there’s a number called JUICE, which teams accumulated by solving puzzles, and more puzzles were unlocked once enough JUICE was collected. Each puzzle contributed 100 JUICE to its own round, and 10 JUICE to all other rounds, with some exceptions. Metas contributed no JUICE, except for Twins and Level One, which were normal puzzles. Athletics puzzles contributed 10 JUICE to all other rounds, and Student puzzles contributed 5 JUICE everywhere.

The numbers that had to be controlled, then, were the puzzles unlocked at certain amounts of JUICE. Setting JUICE thresholds involved making sure that puzzles unlocked at a steady pace, so that big teams had enough puzzles unlocked at any given moment. This number is known as the width or diameter07 Dan Katz notes in a comment to his blog post that Setec <a href="https://puzzlvaria.wordpress.com/2021/01/20/2021-mit-mystery-hunt-part-1-whoosh-big-picture-pros-and-cons-nyeeeow/comment-page-1/#comment-4758">calls this <em>girth</em></a>. Interesting. the number of unsolved puzzles a team was actively working on. I believe we aimed to have a width of a dozen puzzles at the largest.

dubbed as “Yannick’s Sketchy Chart”

Students were unlocked at a rate of one student per 15 JUICE. For most rounds, a new batch of puzzles was unlocked every 100 to 200 JUICE or so, and metas were unlocked towards the end of the round, rather than the beginning.08 For some reason, we internally called this <em>the Jon strategy</em>. We all tend to like the Jon strategy, although supposedly it's controversial? I wouldn't know. The first puzzles of each round were unlocked with enough JUICE: ⊥IW.giga unlocked with 100 JUICE, Stata unlocked with 300 JUICE, Clusters unlocked with 600 JUICE, and Tunnels unlocked with 800 JUICE. This meant that solving 10 puzzles in other rounds unlocked ⊥IW.giga, 30 puzzles in other rounds unlocked Stata, and so on. The exceptions were the Athletics round, where puzzles were unlocked at certain times, and the Charles River, where all the puzzles were events.

We had several simulations to predict when each round would get unlocked and solved by certain teams. For example, over a hundred simulations, the median simulated solve time09 I have no idea what the median is being taken over, actually. Or which teams were being modeled by the simulation. Ask the editors, not me? for the intro round was Friday 4 PM, and conservative estimates for the first solve time was Friday 2:30 PM. These simulations were used to adjust thresholds until we predicted the coin would be found on Sunday morning. These were also used to set “JUICE infusions”, which eventually unlocked all puzzles for all teams. JUICE could also be used to accelerate the hunt if the BDs and EiCs deemed it necessary, which fulfilled our goal of “have knobs and dials to control the rate of the hunt”. Although I don’t have all the data in front of me right now, it’s my understanding that our predictions held up pretty well.

Write, testsolve, revise!

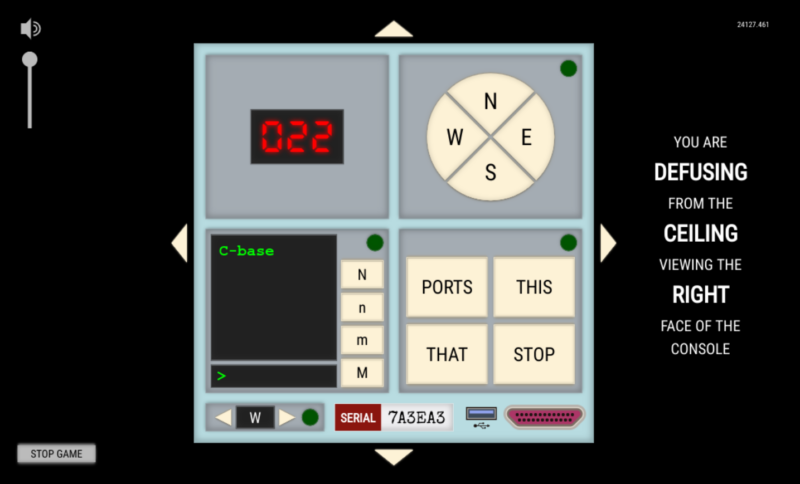

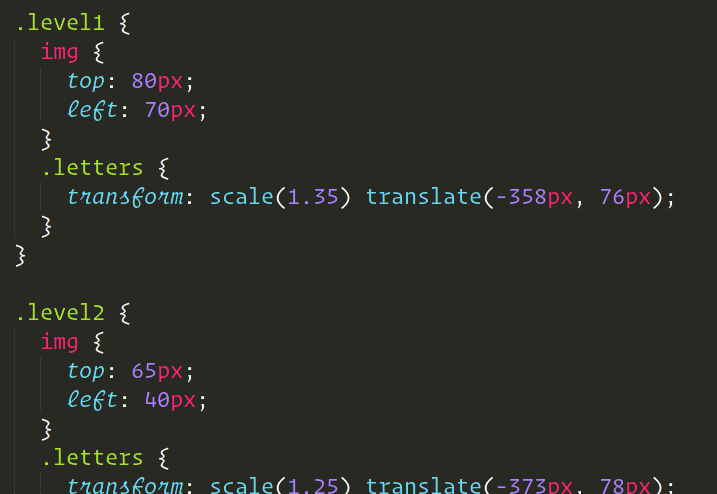

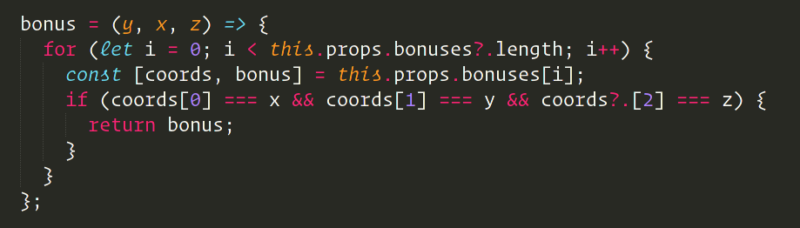

The process that puzzles get written involves several steps, organized through this helpful app called Puzzlord.10 This is a pun on the Pokémon <a href="https://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/Guzzlord_(Pok%C3%A9mon)">Guzzlord</a>, which says a lot about our sensibilities. Puzzlord is Galactic’s version of Puzzletron, a piece of software passed down from generations of past writing teams.

One important concept in puzzle writing is that every puzzle gets assigned two editors, who are in charge of guiding its development. Editors are volunteers who’ve either edited previously for GPH or have written a puzzle before. The editors all had a weekly meeting where they talked about the state of the hunt’s puzzles. The one biggest factor in making my puzzles better was the work my editors brought to the table, which speaks a lot to their patience in working with me, a puzzle novice.

The process a puzzle gets written goes like this. First the author adds an entry to Puzzlord, which begins at the status “Initial Idea”. Once it’s ready enough, the author changes the status to “Awaiting Editor”. Puzzlord shows these puzzles to the EiCs, who are technically spoiled on every puzzle. The EiCs assign two editors and change the status to “Awaiting Review”. The editors then review the puzzle, and then send it to either “Idea in Development”, to mark it for further development before getting giving the go signal to write the puzzle, or they grab an available answer11 If you were wondering why so many puzzles seem to be oddly tailored to their answers, this is the reason why: often the answers are matched to the puzzle, or the puzzle written to have a certain answer. and send it to “Writing (Answer Assigned)”.

Once the puzzle has an answer assigned, the authors then write the puzzle to solve to the answer. This is the stage in which the editors then repeatedly poke the authors to get their puzzle written. Once ready, authors can send it to “Awaiting Approval for Testsolving”, and when the editors approve so, the puzzle gets send to “Testsolving”.

Our testsolve coordinator, Rob, then assembles a group to testsolve the puzzle. Anyone on the team can also independently form a group to testsolve any puzzle in testsolving. The group makes a testsolve session on Puzzlord, and once they solve (or fail to solve) the puzzle, they can leave feedback and rate the puzzle’s difficulty and fun. Testsolving is different from regular puzzlehunt solving in that the groups are relatively fixed, and the time limits are more relaxed, with some testsolves staying open for several days. After a testsolve, the authors and the editors decide whether the puzzle goes to “Revising”, where it gets revised before being sent to testsolving again, or to “Needs Solution”. We aimed for each puzzle to get two clean testsolves before proceeding.

Once a puzzle is past testsolving, it then goes through the production pipeline. Authors write the solution and then send it to “Needs Postprod”. Postprod here stands for post-production, which is the process of converting the puzzle and its solution from, typically a Google Doc, to a webpage that gets served on the hunt website. Sometimes this is as simple as converting it into HTML, sometimes it involves some fancier formatting, and sometimes it involves making interactivity work.

Once the authors or postprodders are finished, they move the puzzle to “Needs Factcheck”. Factchecking is the process of making sure a puzzle works correctly, has no ambiguities, and is accessible. One way to think about it is that factcheckers try to minimize the number of errata sent during the hunt, although that’s only one of their responsibilities. Factcheckers make sure that images, logic puzzles, and crossword clues meet certain standards.

Factcheckers can send the puzzle back to “Revising” if it needs big revisions, or “Needs Minor Revisions” to request some small revisions. From “Needs Minor Revisions” authors can then send it to “Needs Copy Edits”. Factcheckers can also send it to “Needs Copy Edits” directly. Then the copy-editors, well, copy-edit the puzzle, and request whatever changes needed.

Then the copy-editors send it to “Needs Hints”. The authors then add some pre-written hints that hint-givers can edit to give teams during the hunt. When they’re done, they request approval from their editors, who can then (finally!) send the puzzle to “Done”.

Writing puzzles is hard

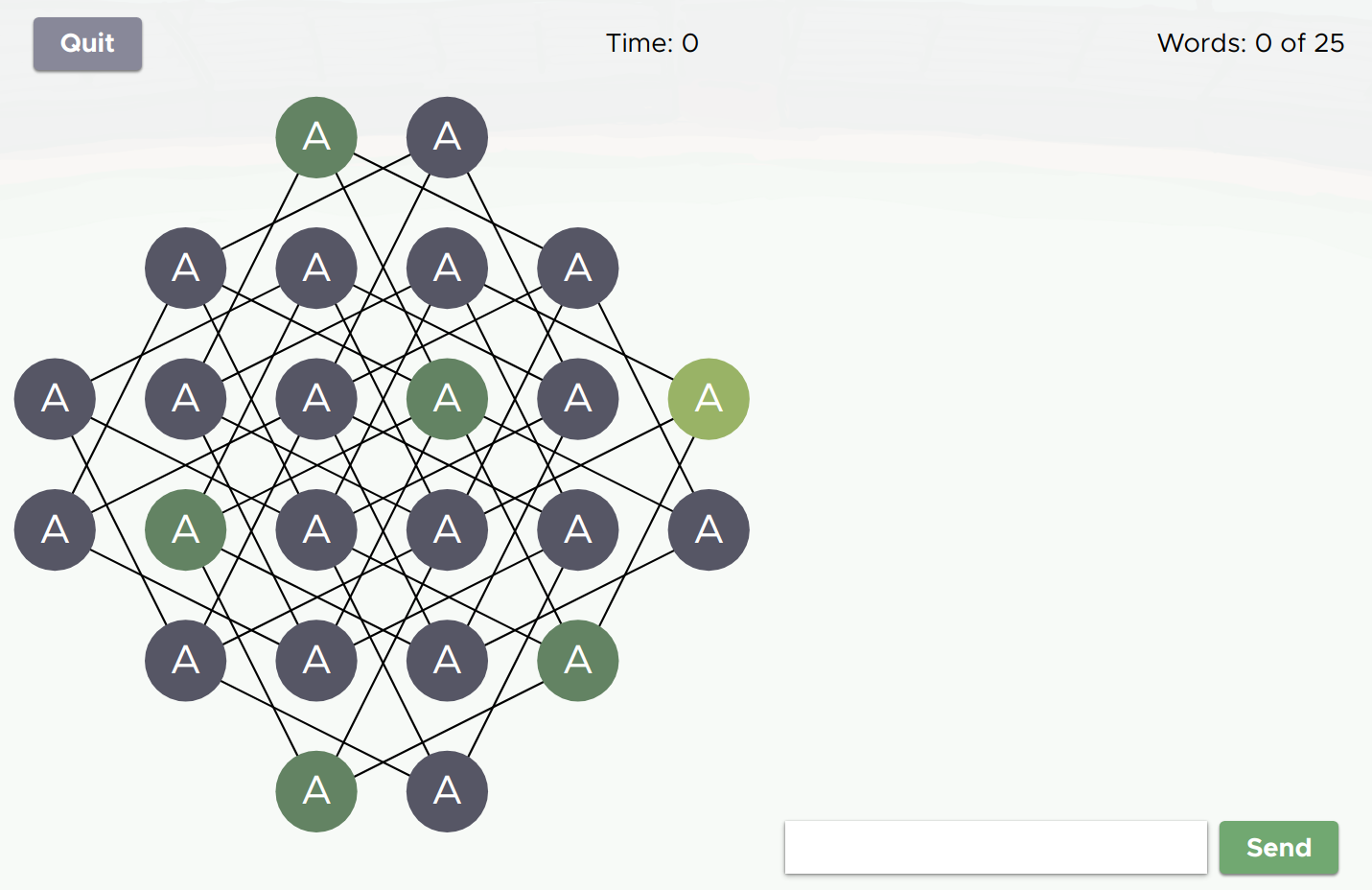

Spoilers for the puzzles Everybody Dance Now and Charisma.

There are two puzzles in the hunt that I could truly claim a decent amount of author credit for: Everybody Dance Now and Charisma. These puzzles do have their own authors’ notes, which you can read if you want more information, but I suppose I’ll talk a bit more about things that didn’t quite make the authors’ notes.

Everybody Dance Now is the first puzzle I wrote for this hunt, which means that it’s the first puzzle I wrote, ever. Its production was stalled for quite some time. It was in Puzzlord since January, only started development during April, and only got ready for testsolving in June. A lot of the stalling was because the idea for the puzzle evolved several times, from using bigons to homophones to logic puzzles to other things. The final puzzle didn’t end up being very puzzly nor very novel, but I’m very proud of it nonetheless.

Charisma is a wonderful example of how helpful feedback was for making my puzzle. My two editors, Rob and Chris, as well as Jakob, who testsolved an earlier revision, really deserve the credit for coming up with many of the ideas. It was Rob who had the idea of using music videos, Chris who had the idea of making a word search, Jakob who convinced us it was feasible, and all three of them helped with constructing the grid for the puzzle. This is definitely a puzzle I couldn’t have written alone, and finishing this puzzle definitely made me feel more confident in my abilities.

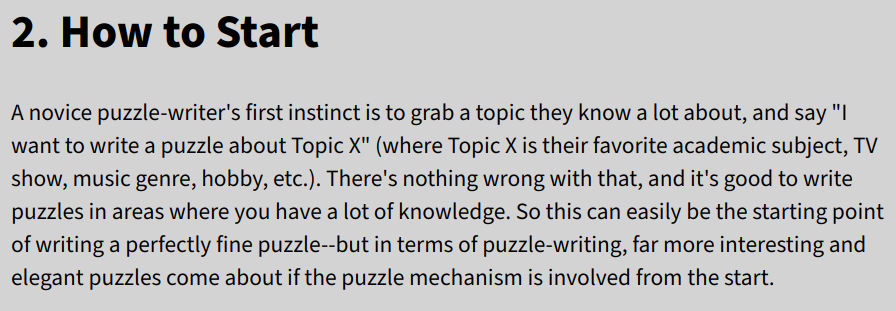

I think the thing about puzzle ideas is that they aren’t cheap. That is to say, it’s easy to come up with the theme of a puzzle, but coming up with the actual mechanism is much harder. As a novice author, my first instinct was “I want to write a puzzle about X”, as David Wilson so clearly states in his puzzlewriting guide. And all of the puzzle ideas I placed on Puzzlord were “I want to write a puzzle about X”. There’s a theme, which is one part of the puzzle, but the mechanism just wasn’t there.

talk about an attack

And the mechanism is the hard part, and the part I struggled a lot in coming up with. The first drafts for Charisma, for example, were all basically ISIS puzzles.12 Short for Identity, Sort, Index, Solve, a type of puzzle whose steps are identify, sort, index, solve. Not particularly original by any stretch. To be fair, these were the things I came up with four months after my first big puzzlehunt. Now, I’ve solved thrice as many puzzles as I have since when I first had these ideas, and my puzzle ideas now are… still pretty bad. Eh. They’ll get better with more time, I suppose.

Some comments on rounds

Spoilers for the metas for Yew Labs, Green Building, Rule of Three, Twins, and MacGregor House.

My general feeling is that the 2020 Mystery Hunt had a theme that was relatively unconstrained meta-wise. The hunt was about a theme park, and many things could be the theme for a theme park; there was a Grand Castle and YesterdayLand and Spaceopolis. That freedom allowed Left Out to write brilliant rounds like Safari Adventure or Creative Picture Studios. On the other hand, our theme was slightly more constrained: the metas had to be themed around MIT buildings and locations. I think this worked out to be to our advantage in the end, in the way that restrictions breed creativity.

The wrap-up talks about some of the metas and some info behind the scenes, and many of the metas have authors’ notes in the solution page. But here are some things that didn’t quite make it to the authors’ notes:

- We had a lot of different ideas for the name of MIT in the alternate universe. Before then, we mostly called it “altMIT”. The two main options seemed to be either having the acronym TIM, as in the Technical Institute of Mysteries, or ⊥IW, as in the puzzles.mit.edu/2021 of the World.13 One proposal for the W was <em>wechnology</em>, which I thought was brilliant. Of course, I was a proponent for <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_lMu8V5Xa90"><em>wumbology</em></a> myself. I think WIT was also on the table or something like that. The final decision was influenced by the Yew Labs meta, Enter the Perpendicular Universe.

- The Green Building meta was the first one to be written for the hunt, written even before the theme was selected. The original proposal, in fact, required 22 feeder puzzles, rather than the 13 there are now.

- The Stata Center meta is hands down the puzzle in our hunt that was most heavily testsolved. This was because it was revised multiple times, and due to the size of the puzzle it needed around five to seven people per testsolve. It was testsolved to the point that during one of our Big Test Solves, we had a hard time finding people who weren’t spoiled on the puzzle to work on it.

- Rule of Three, the metapuzzle for ⊥IW.giga, was nerfed during the hunt after the BDs and EiCs deemed it necessary. The original puzzle didn’t have the image of the three circles in the bottom. I wasn’t there for it, but I imagine it was a pretty tense decision after seeing the lack of progress in that round. I always felt that Rule of Three was one of the most challenging metas in our hunt, and it took us several hours in our testsolve to realize it was about syzygies. Ah well.

- Another fact about the ⊥IW.nano metas that wasn’t mentioned in the wrap-up: they had a three-two-one motif! Rule of Three, then Twins, then Level One.

- The MacGregor House meta is truly brilliant. A truly masterful piece of work. Our hunt will be remembered for many things, but the sublime genius of this elegant metapuzzle will be talked about in hushed whispers of awe hundreds of years from now. I tell you now: there will never, ever be a Mystery Hunt with a meta involving two feeders, ever again.

- It was mentioned in the wrap-up that the Athletics round was the last round to be added to the hunt, but it wasn’t mentioned that we added it in September, three months after we’d finalized every other meta! Each of the three Athletics subrounds were themed around a different kind of puzzle, and the Basketball puzzles were all puzzles that needed teamwork. The Basketball puzzles were some of the last puzzles to be written for the hunt: the answers for You Will Explode If You Stop Talking and Divided Is Us were assigned in December, and Boggle Battle was first implemented in early January. By then, the answers were unclaimed for so long that most of the testsolvers knew what the final answer was.

Non-author’s notes

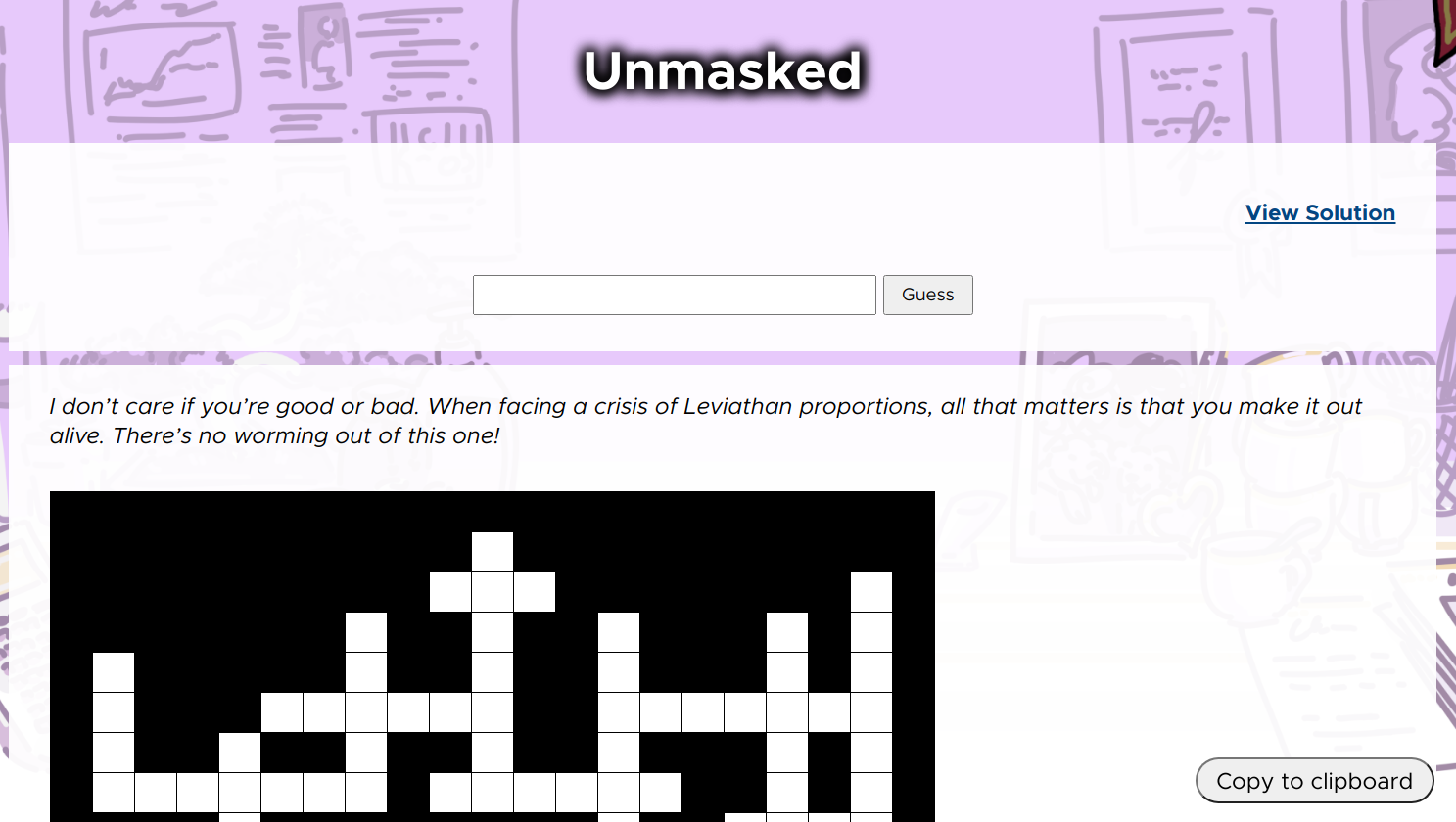

Spoilers for the puzzles Unmasked, ★, An American in Paris, Dolphin, Squee Squee, Questionable Answers, and the Clusters meta.

I’ve enjoyed getting to know all of the puzzles in the hunt. It feels so, so satisfying to know how every puzzle in this hunt works. Throughout the year, I’ve gotten to see these puzzles develop, and so I have some notes about them. These didn’t make it into their authors’ notes, because they’re from me, and I am not an author for these puzzles. I really don’t want to steal the authors’ thunder, so please do look at the original puzzles and their solutions, and take my comments with several grains of salt.

These puzzles are in order of how they’re listed in the list of puzzles page. There’s more comments about puzzles I testsolved specifically, but that’s in a later section.

- Common Knowledge, Circles and Simplicity. All of these are minimalist puzzles by Lewis. All of these are ones I kind of struggled with in testsolving. All of these are puzzles I deeply admire for being so simple, and I one day wish to write puzzles as elegant as these.

- Unmasked. The only reason I have coauthor credit here is because Mark saw EIDOLON, wanted to write a Worm puzzle, and grabbed me. And then Mark did all of the work; I only helped with writing a handful of crossword clues. I’m particularly proud of “A terrible wingman, if they disliked time?”

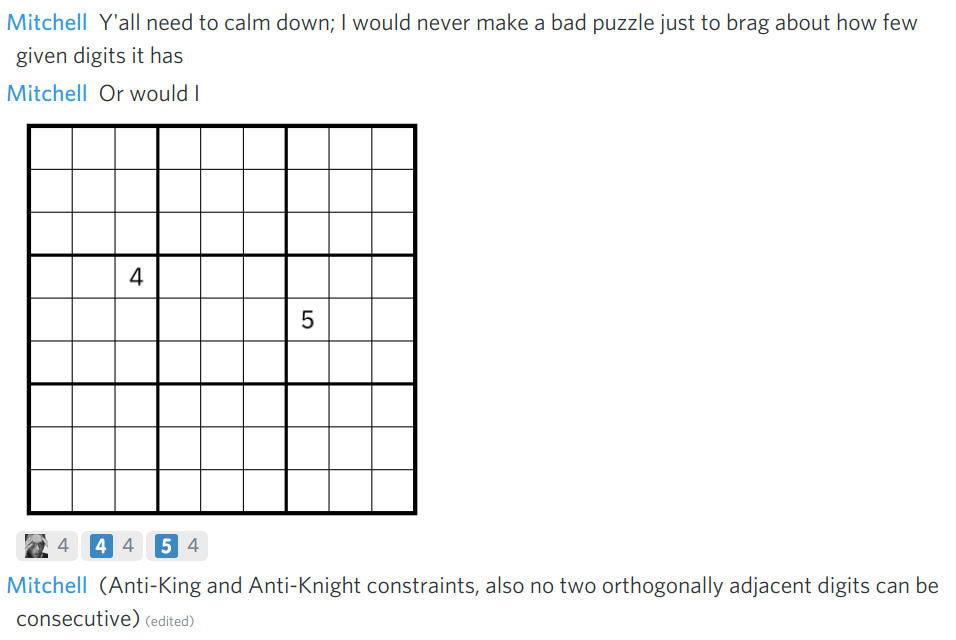

- ★. Fun fact: none of the testsolves actually solved the Miracle Sudoku. Also, the only reason this puzzle got written is because Mitchell Lee, the author behind the famed Miracle Sudoku, is part of the writing team. He aptly co-authored Fun With Sudoku and The Greatest Jigsaw, which was originally a Samurai Sudoku.

- Fun fact 2: One day, we were talking about Sudokus with few given digits. The next day, Mitchell sent a message saying he would never make a Sudoku just to have very few given digits. Immediately after, he posted what would become the Miracle Sudoku. It only took a couple of days for Cracking the Cryptic to make a video about it, which became their second most viewed video of all time.

birth of a legend

- Over 9,000: an Abbreviated Yet Awesome Tour Of Your First Equally Excellent Puzzle Mechanic. This didn’t end up being in the authors’ notes, but you should read this excellent Reddit comment about its construction.

- An American in Paris. I helped provide the Tagalog clue, and my friend, Pleng, provided the Thai. Feedback from after the hunt indicated that the Thai was one of the harder clues to piece together for this puzzle, with even native speakers having a challenging time figuring it out. Oops, I guess?

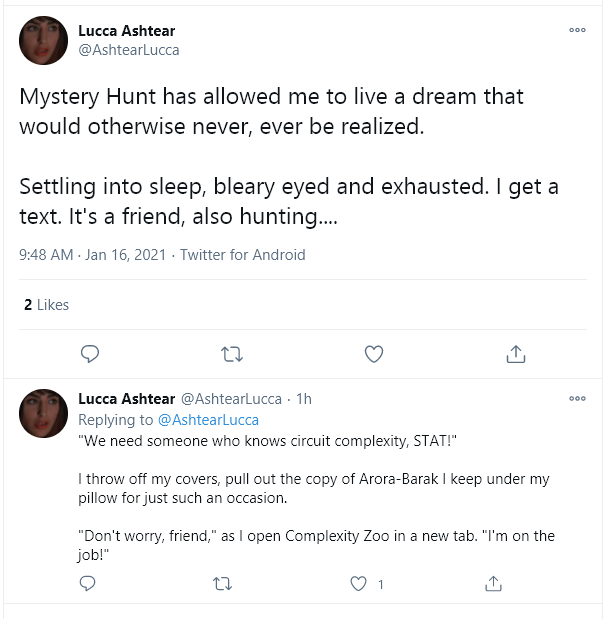

- Complexity Evaluation. In case you missed it, the author is Josh Alman, who was one of the co-authors of this seminal paper on matrix multiplication. That paper is the subject of this SMBC comic. If being in an SMBC comic isn’t fulfilling a life goal, I don’t know what is. Also, this puzzle spawned this excellent tweet.

dont we all dream this

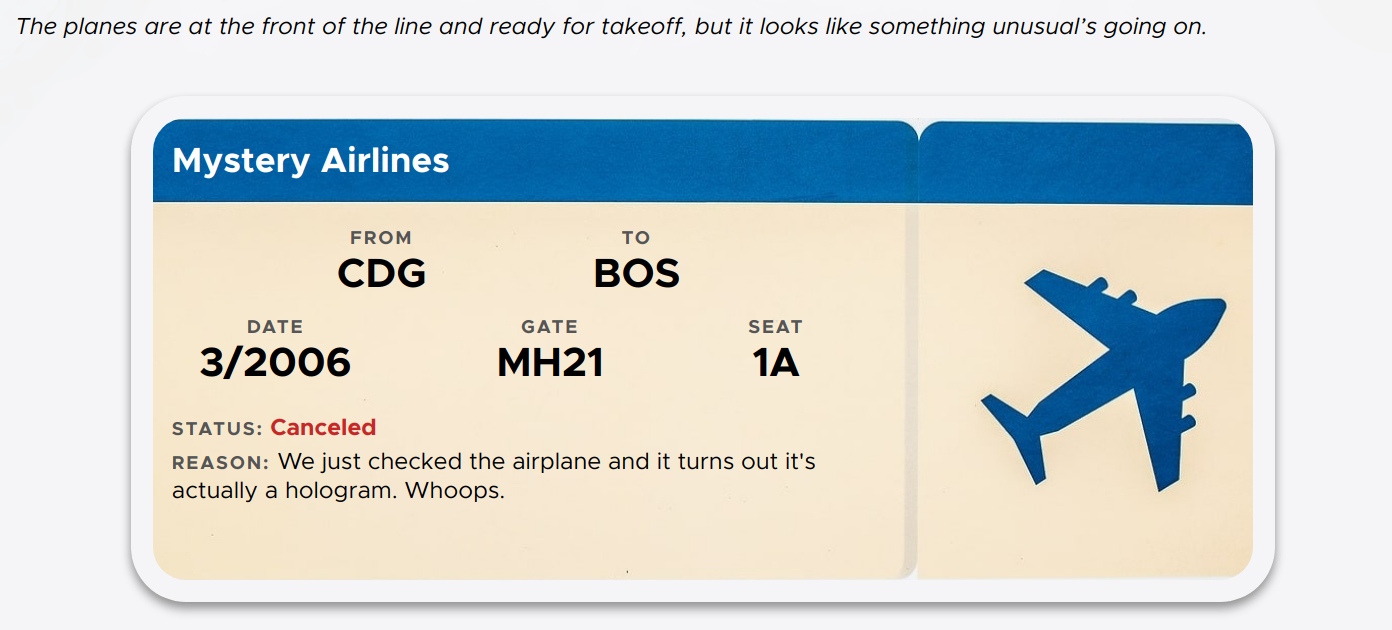

- Dolphin. I was the factchecker for this puzzle, which meant I had to watch fifteen GameCube commercials over and over to verify that the quotes were only said once, and that they unambiguously solved to the given answer. It was at that moment I understood how difficult and important a job factchecking was. I ended up factchecking no other puzzles.

- Love at 150 km/h. I love luge. And I love this puzzle. Please look at this puzzle. Please enjoy all the beautiful art and music for this puzzle. It is brilliant. A true work of art.

- Powerful Point. The author’s notes for this puzzle is one of the best in the entire hunt, in my opinion.

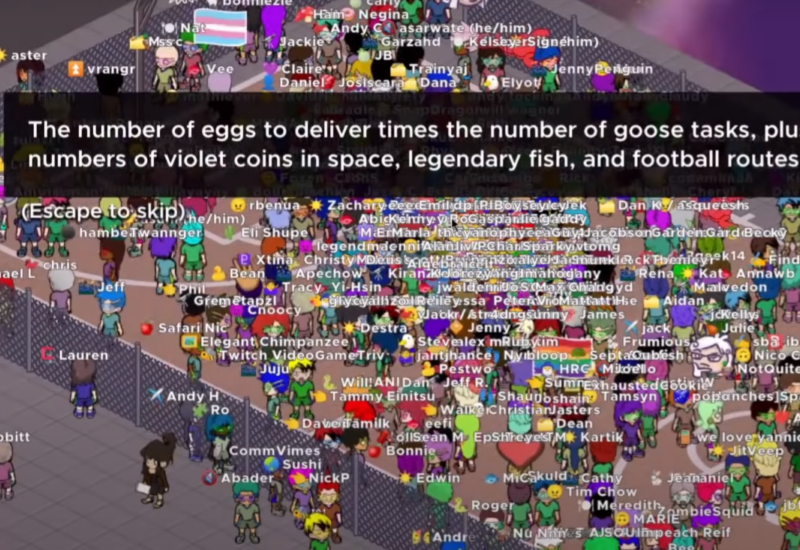

- Athletics navigation puzzle. For this navigation puzzle, Josh, Yannick, and I went around campus and took pictures one December morning. As suggested by the following picture, I do not know how footballs work. Did you know that Josh bought these balls in a Black Friday sale?

this is how footballs work right

- Squee Squee!. The (intended) final step for this physical puzzle is smashing the pig to extract a sheet of paper to get the answer. We got a lot of hint requests and emails about this. Quote one email: “You ask if we have it in us to do unspeakable things to our pig, seconds after telling us we’ve done a great job raising and caring for her?!”

- Treasure Maps. Mark jokes in the author’s notes that this is meant as a response to “all the music ID puzzles that I find impossible to solve.” It turns out that the kinds of puzzles I like writing tend to be the polar opposites of what Mark appreciates, like Everybody Dance Now. (He did tell me he likes Charisma, so that’s something.)

- Doing Some Gardening. For the longest time the title of this puzzle was “A Garden”. It made it all the way to the “Done” status on Puzzlord before we realized that the Clusters meta required its title to start with D, not A. Oops.

- Clusters meta. This was one of the metas that had to be revised after we made the decision to go remote. Previously, the separation between Greek and Latin words was even clearer, because the puzzles with Greek answers you’d have to find in MIT, and the puzzles with Latin answers you’d have to find in ⊥IW. The meta ended up being workable without that, though.

- It’s Tricky. I swore to myself that I would never make a TikTok account, but unfortunately, I have succumbed as a victim of this puzzle and have appeared in a TikTok. I have helpfully linked the TikTok video here, but I am only doing this so that people don’t talk about it too much in the comments. Dear readers, have pity on me and my dance skills.

From the new world

The play within a play

The wrap-up presentation has a lot of discussion about prototypes and concept art, and I want to go into a little more detail in this section.

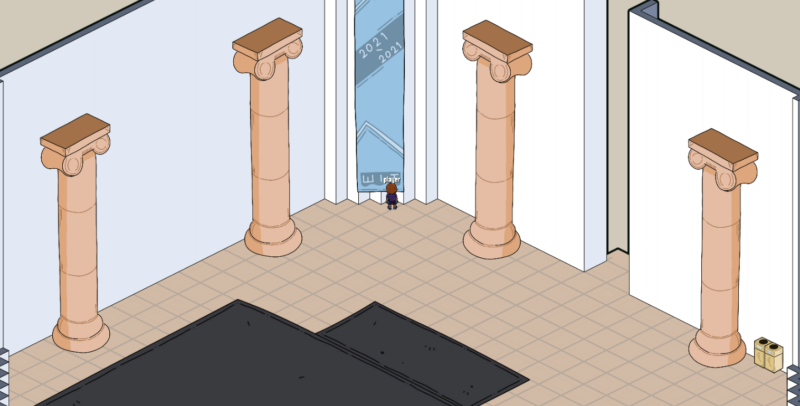

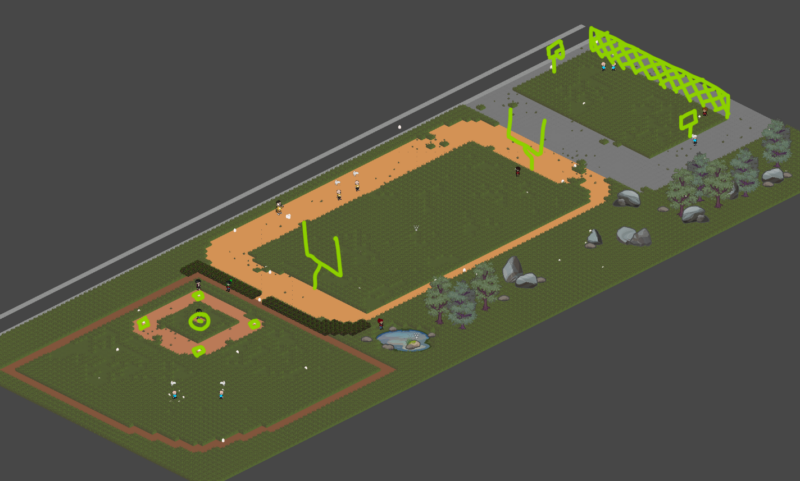

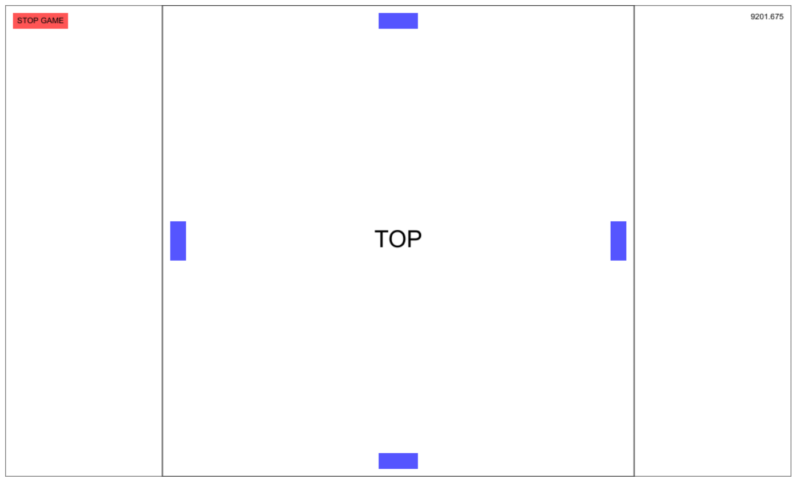

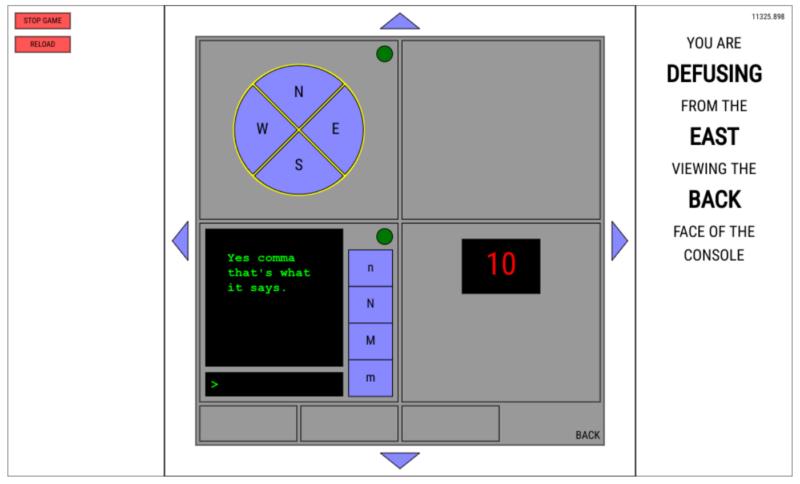

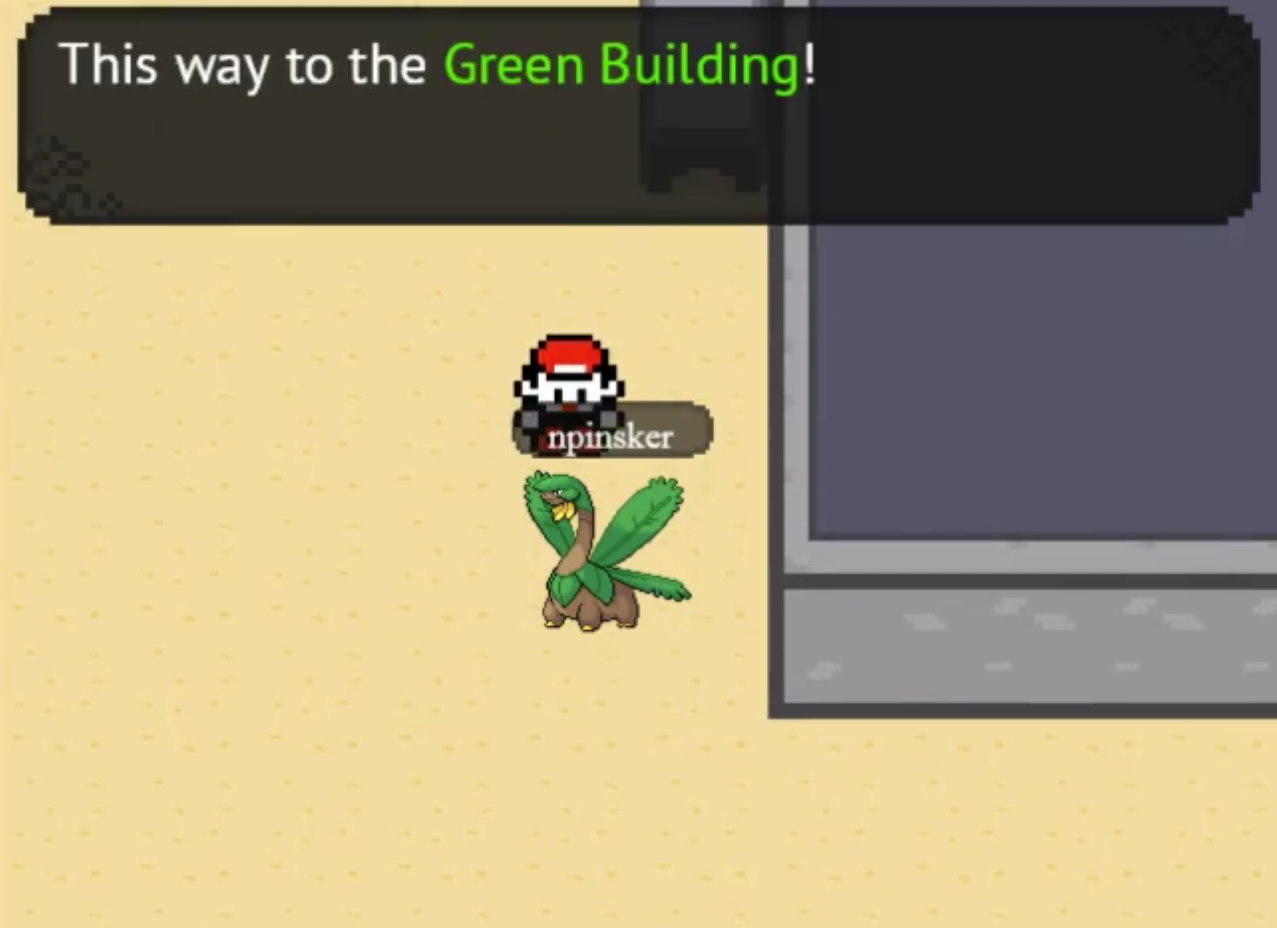

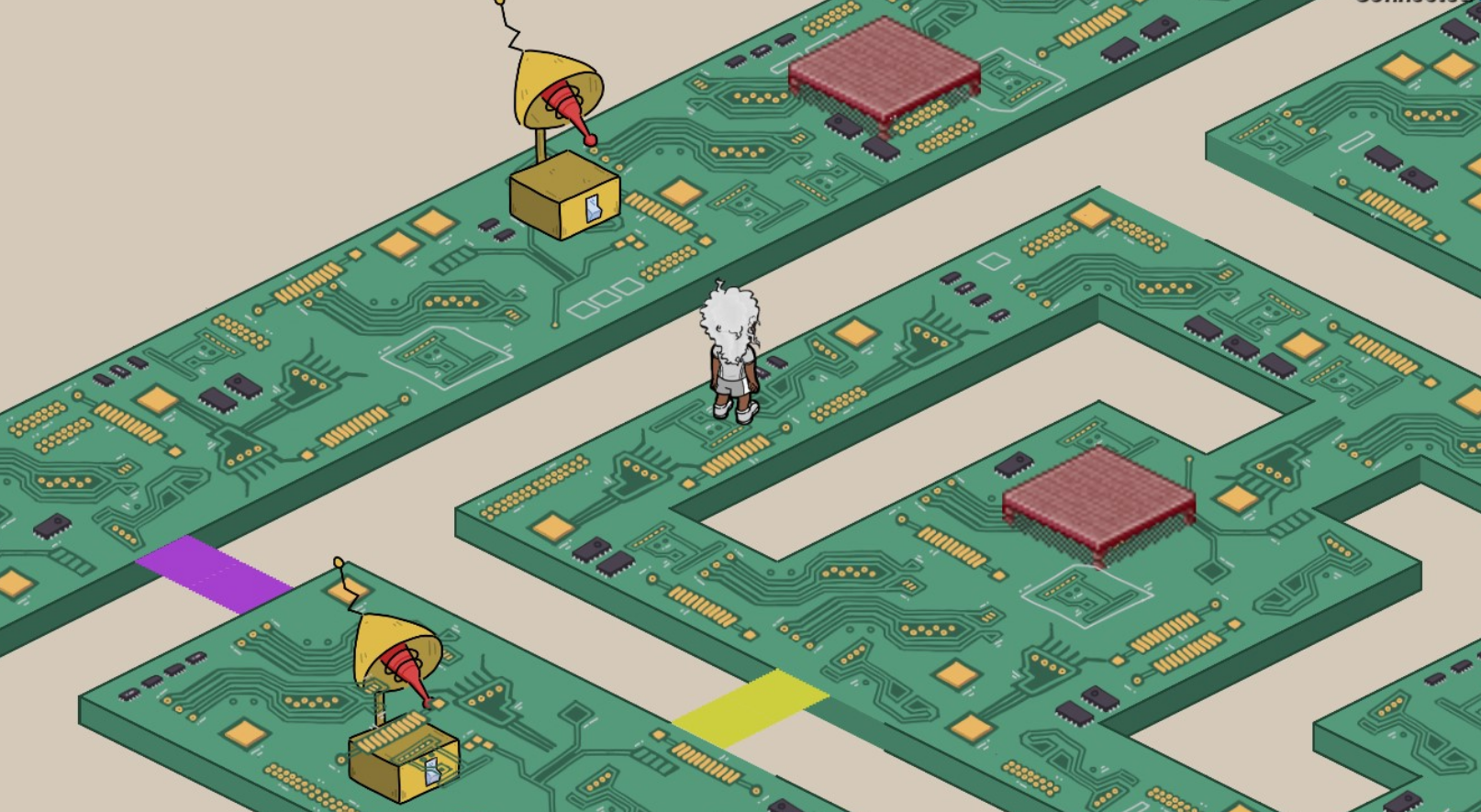

The earliest prototypes for the MMO were the 2D Pokémon-style ones shown in the slides, which already existed in February. The prototype was made in HaxeFlixel, the same game library used to make Love at 150 km/h. It’s fitting since Nathan was one of the people who worked heavily on both.

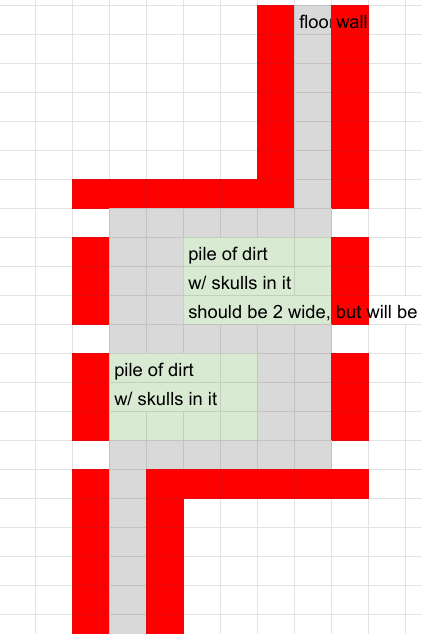

pokemon vibes

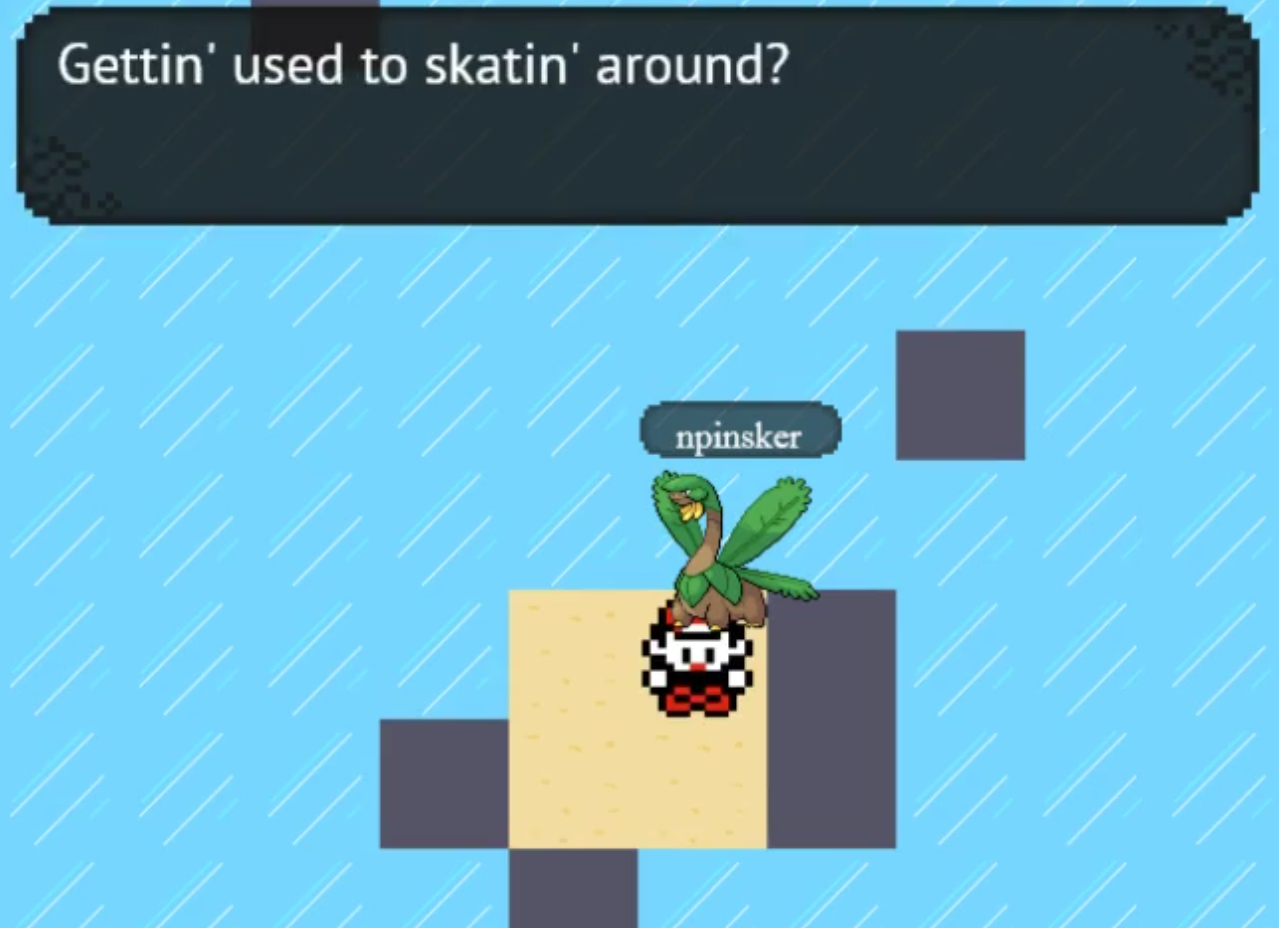

Some of the earliest things implemented in the prototype were the Infinite Corridor being actually infinite, and an ice puzzle originally intended for a frozen Zesiger Center. It was also initially planned that maps would be designed in the Tiled map editor.

ice puzzles are fun… but are they that fun

The 3D picture of the Green Building in the slide comes from a style demo that Lennart made when trying to figure out what the MMO would look like. This one was a WebGL project made in Unity.

more pokemon vibes

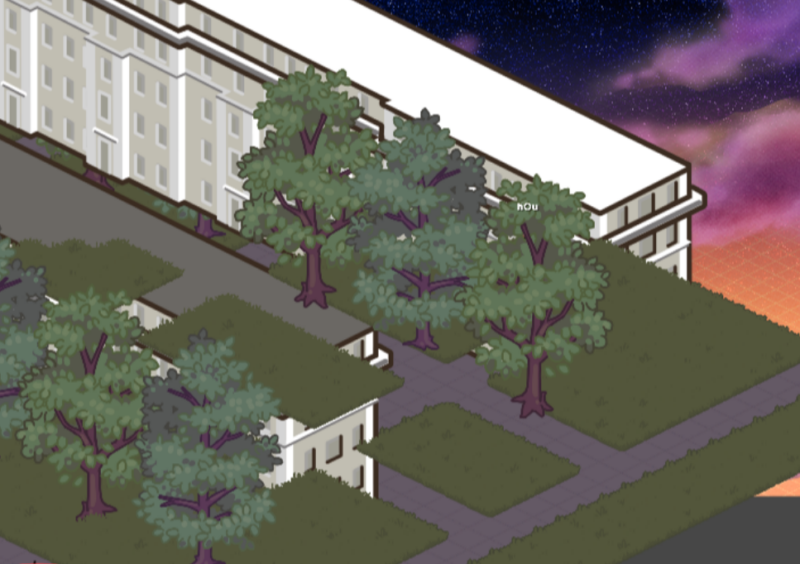

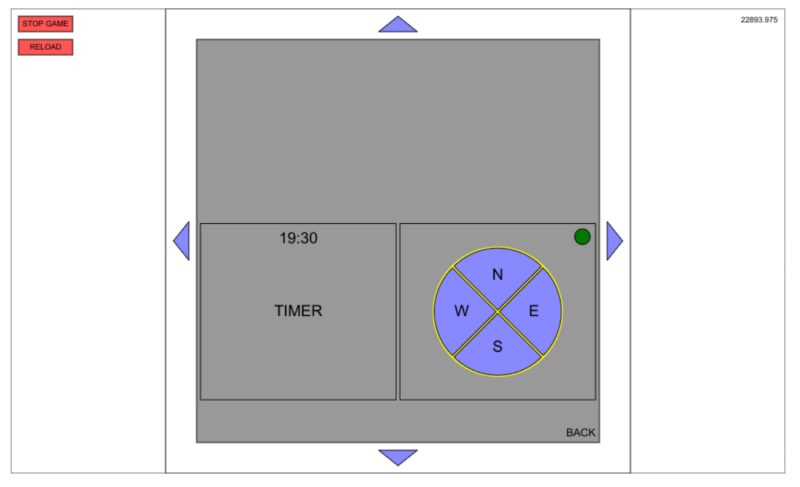

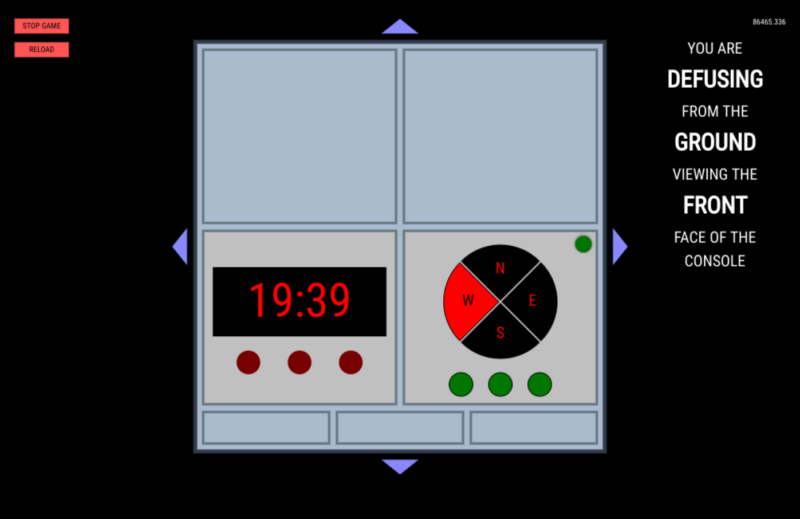

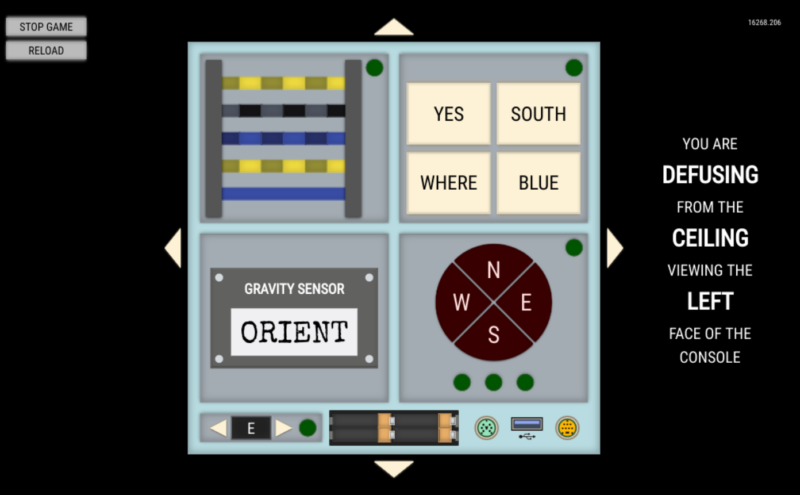

Once the theme was finalized, the decision to write the client in Unity happened in mid-March, along with some other important art decisions. Part of the rationale is that Unity had more built-in components than HaxeFlixel did, and also Unity natively supports isometric grids.

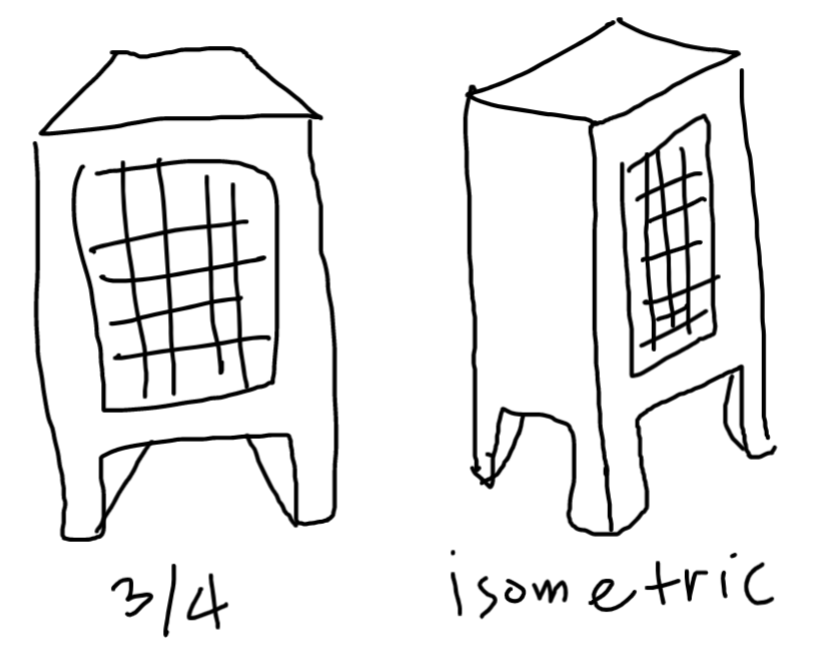

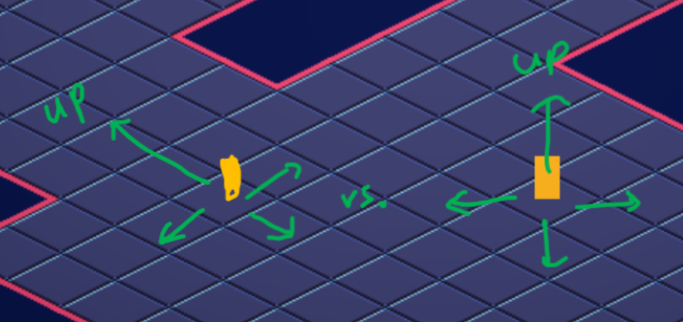

As to the art choices. 2D or 3D was a pretty big decision; I remember there was an entire meeting about it and two pages worth of pros and cons. One primary reason why it was 2D rather than 3D was because the art leads felt like it’d lead to a higher level of polish, and personally, I think that turned out to be a great decision. Another decision was that the grid is isometric rather than 3/4, which means that it’s oriented kinda diagonally.

my BEAUTIFUL artwork

The rationale is that an isometric perspective would better portray the scale of tall buildings despite being in 2D. There was some concern about the keyboard controls being weird in an isometric grid, since the arrow key directions didn’t align with it. This meant that either the up key moved northwest or northeast, or that you had to hold two keys to move along the grid. The game client developers decided to go with the latter after some playtesting feedback.

they went with the latter in the end, and dropped the tile-based movement

I’m less aware of the decisions that led to the development of the MMO server. The things I know about it are that it’s written in Go, and that it’s called Tempest, which is an awesome name. I kinda wish that the MMO client also had a cool name, because “MMO client” isn’t as snappy, but eh. There’s a FAQ in the Tempest README that explains why the name was chosen:

it IS a cool name

The wrap-up already has some cool concept art, most of which was collected and drawn in March while the style was being decided. Here are some closeups of the concept art from the slides.

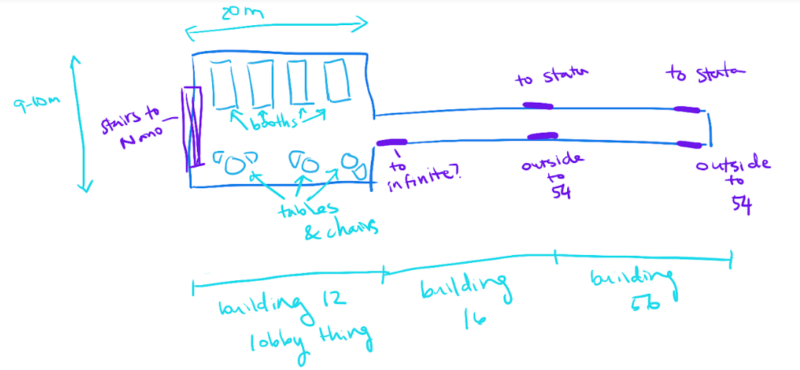

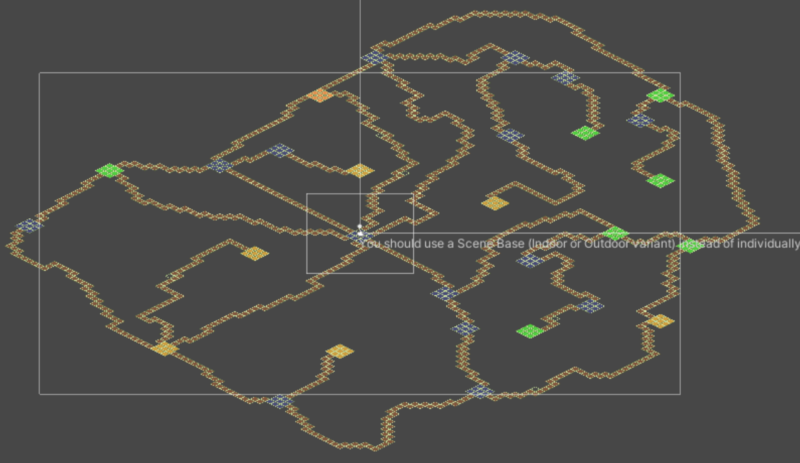

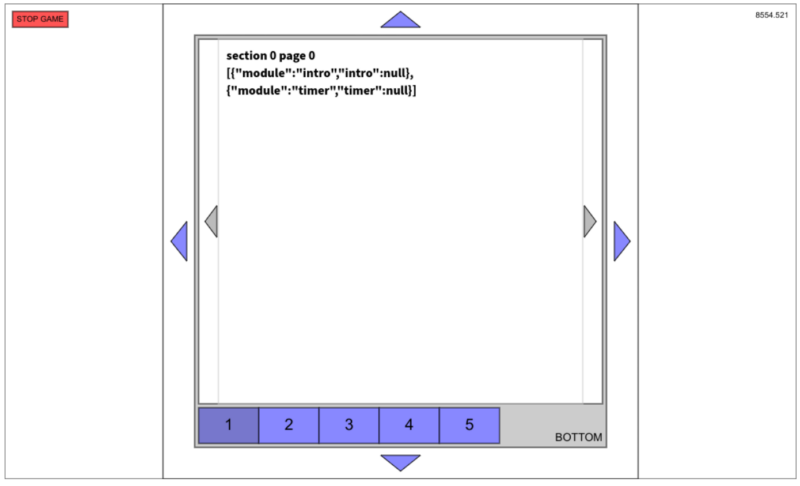

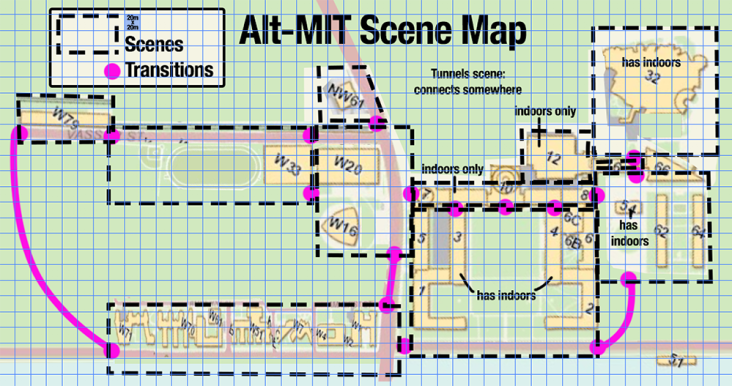

Here’s an early map of the MMO’s scenes, made some time in May, when the name ⊥IW wasn’t finalized yet. Lots of changes have been made since then.

notably, the sailing pavilion is not connected

Here are some notes from early drafts of the MMO’s style guide. Initially, ⊥IW was supposed to be more gloomy, and I’m glad it went in a different direction.

altMIT

Mostly vegetative decay, but some (nano, Broad) are envisioning changes to the shape of the building

Maybe play with weird lighting, grays; think about leaning towards cooler, ashy lighting/feel (very depressing overcast midwinter feel), possibly some smog, Londony, dismal

…

“Like the way MIT does when you’re there in the middle of winter break and everyone is gone”, levels of isolation and solitude, things kinda anxious

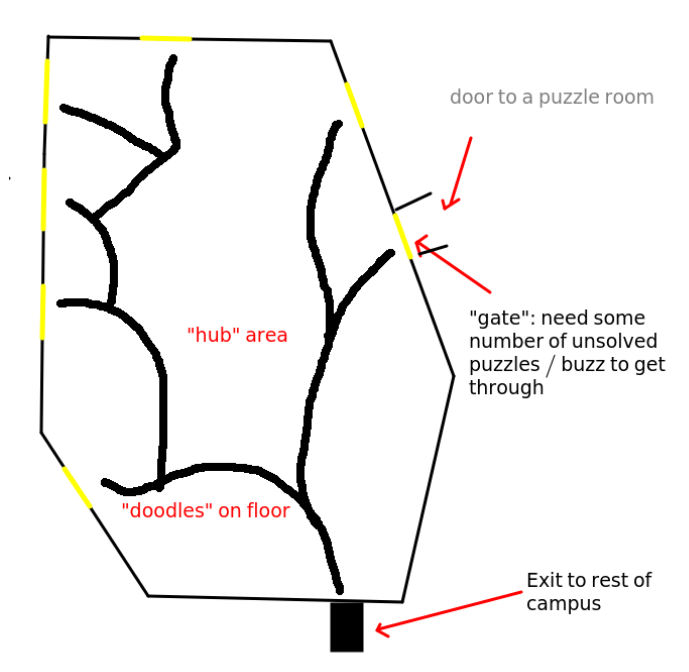

Each of the areas in the MMO had a certain navigational puzzle, which you needed to figure out in order to find puzzles in a certain round. As mentioned earlier, the Z Center, for example, was supposed to have a sliding ice puzzle. Also, we had these things called post-meta interactions, where after your team solves a meta we would schedule an interaction where you can put that answer into action. The original plan, in fact, called for these to be more tightly linked together!

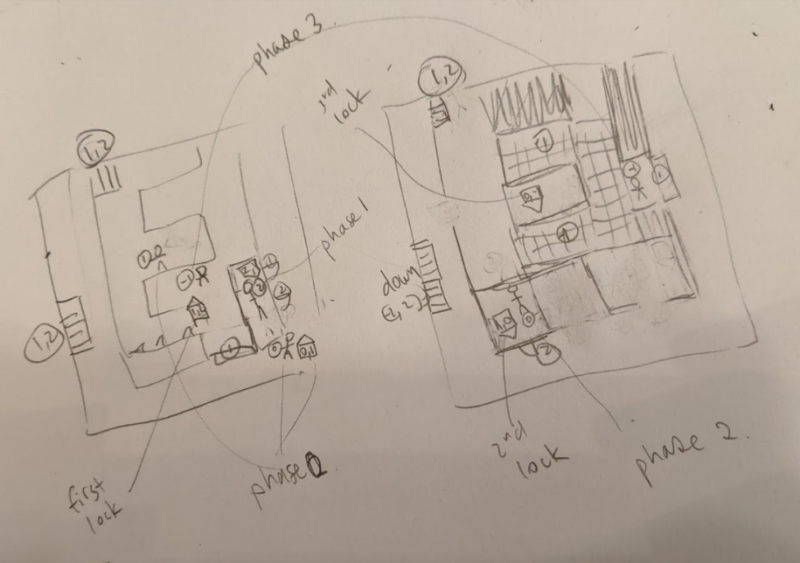

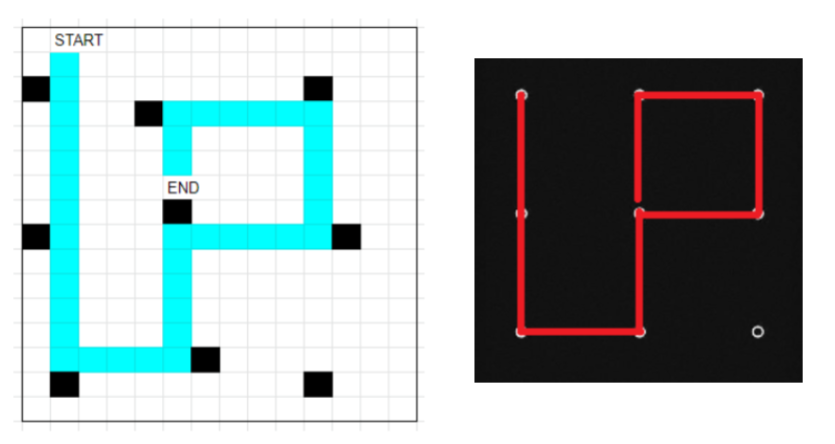

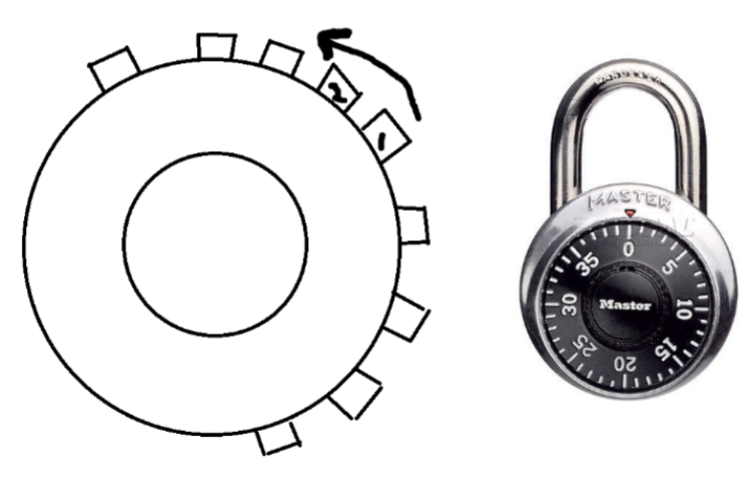

Back in March, when we still thought the hunt would be on-campus, the post-meta interactions would be physical interactions that ended with sending some object to ⊥IW via a portal. These objects would make some new area in the MMO available. Applying the navigational puzzle concept to the new area would lead to some sort of code that encodes some sort of key. Teams would then go to a room and open a physical lockbox with this key, to get one component of the “final object” they need to finish the hunt.

An example would make this clearer. Recall the plan for the Z Center to have some sort of sliding ice puzzle. The interaction would’ve ended with Yew Labs sending an ice cube to ⊥IW. This would then allow a new area to be accessed. And then the path that this would draw out could correspond to a phone-style unlock pattern.

is this even a valid unlock pattern

Or in the Infinite Corridor, the interaction would’ve ended with sending a pie, which opened a new circular corridor. The rooms along the corridor still have portals, but this time, they encode the combination to a combination lock.

this one sounds neat

These ideas were cut when it was decided that lockboxes didn’t really make sense in-universe. Then there was the concept of having a portal where teams would retrieve objects, which was cut for other reasons, like concerns about length and practicality with being remote. The core idea remained: we wanted to have some sort of interaction with teams after each meta. This later became the post-meta interactions that I’ll talk more about later.

Drawing a virtual world

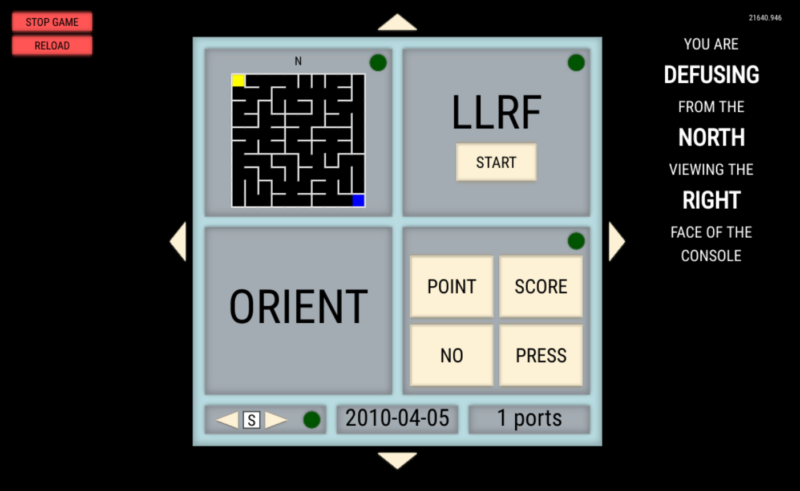

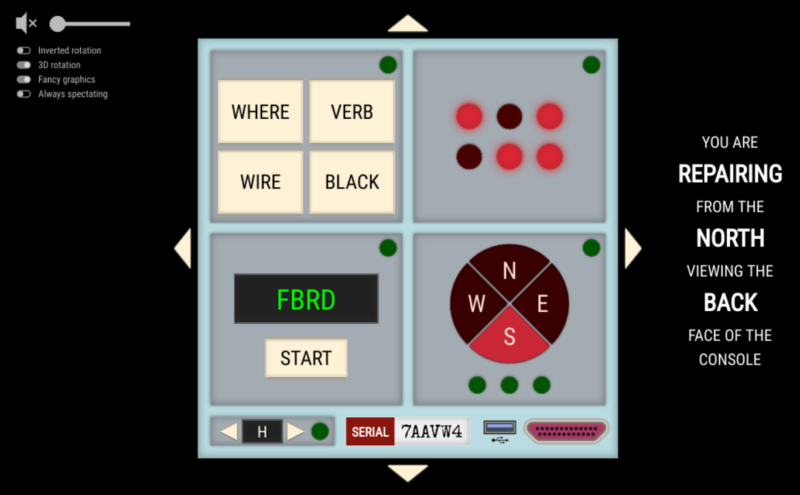

Spoilers for all navigational puzzles and all football puzzles.

The MMO and art subgroups had their own weekly meetings, beginning some time in March. Art meetings happened on Monday nights, and MMO meetings happened on Tuesday nights, before they switched to Monday nights. So if you’re keeping track, that’s four regular meetings: exec meetings, art meetings, MMO meetings, and editor meetings.

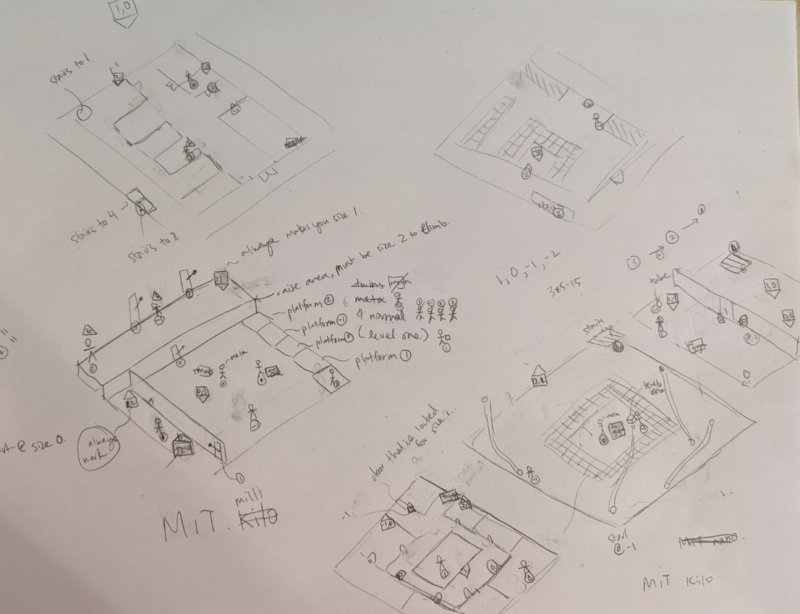

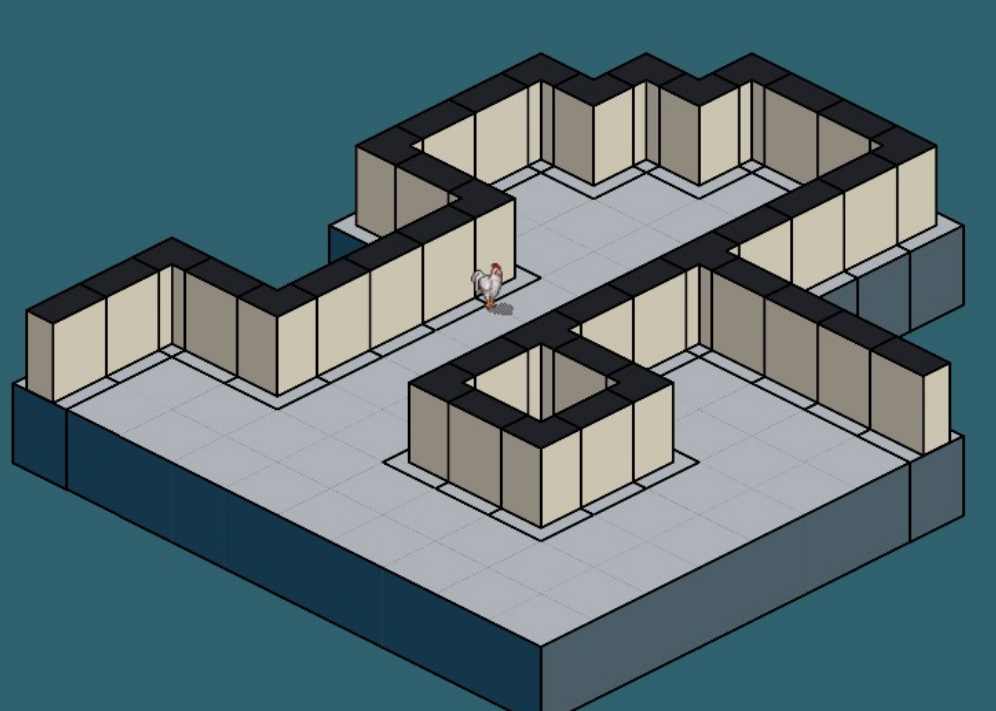

Let me sketch a rough timeline of when things happened. The basic structure of the MMO, including the player code and client-server communication and some of the decisions that led to that, were set in place by mid-April. A demo of the Green Building, the first area built in the MMO, was up by the end of April. The “demo” here was just a skeleton—the walkable areas and the walls were set, but nothing else.

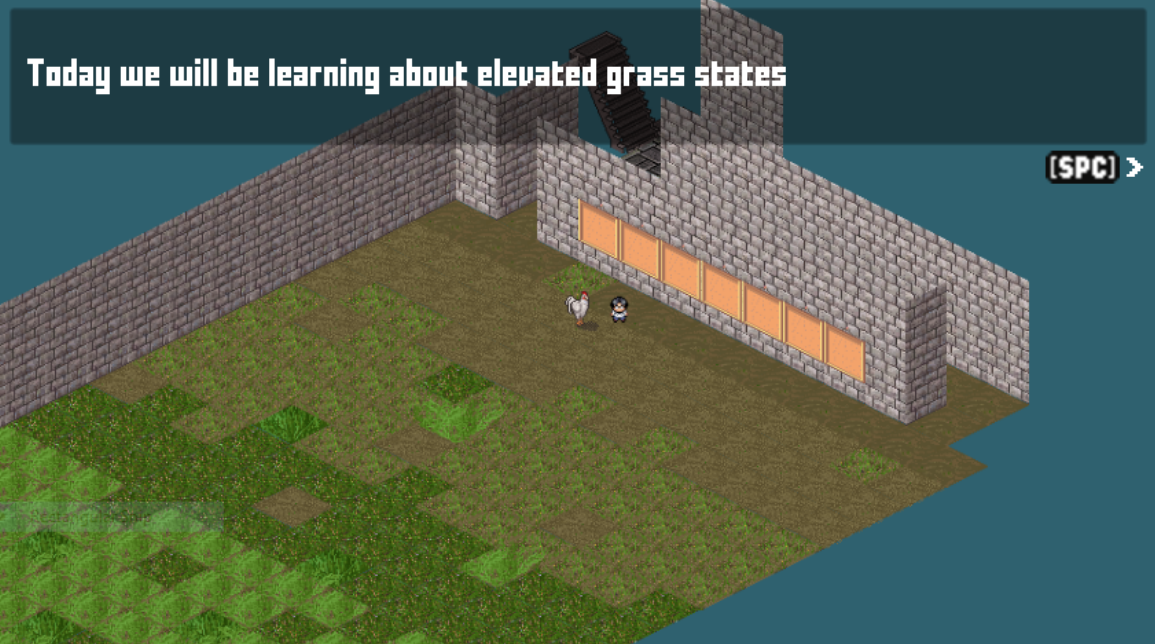

idk what elevated grass states are

The MMO and art teams really did a lot to make contributing as accessible as possible to everyone who wanted to help, and they wrote up a lot of internal documentation about how to do things. I remember a tile style guide that specified the scale: “1 unit in the MMO is 1 meter IRL… most doorways will be 2 units wide, wide hallways will be 3 units, narrow passages will be 1 unit”. Once during April there was even a Green Building build session, where Lennart and some other people streamed themselves working on the MMO.

But even during May, there were still several things being worked out. A lot of work was still being done in test rooms, and the player sprite was still… a chicken? The proportions for what people sprites would look like weren’t even decided yet.

miss being a chicken

proportions are hard

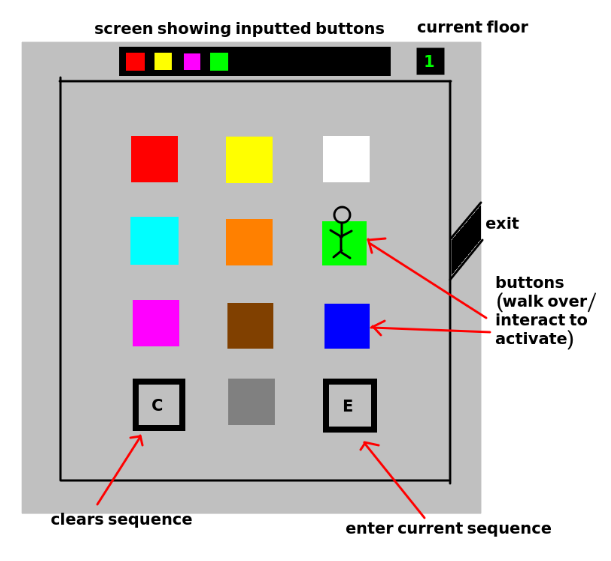

Here’s some sketches of what the Green Building navigation was originally intended to look like. Originally, the elevator room didn’t have real buttons, and you needed to walk on the floor to activate them. I’m glad that this eventually changed to the better UI of an actual grid of buttons.

moving around is a lot slower than clicking

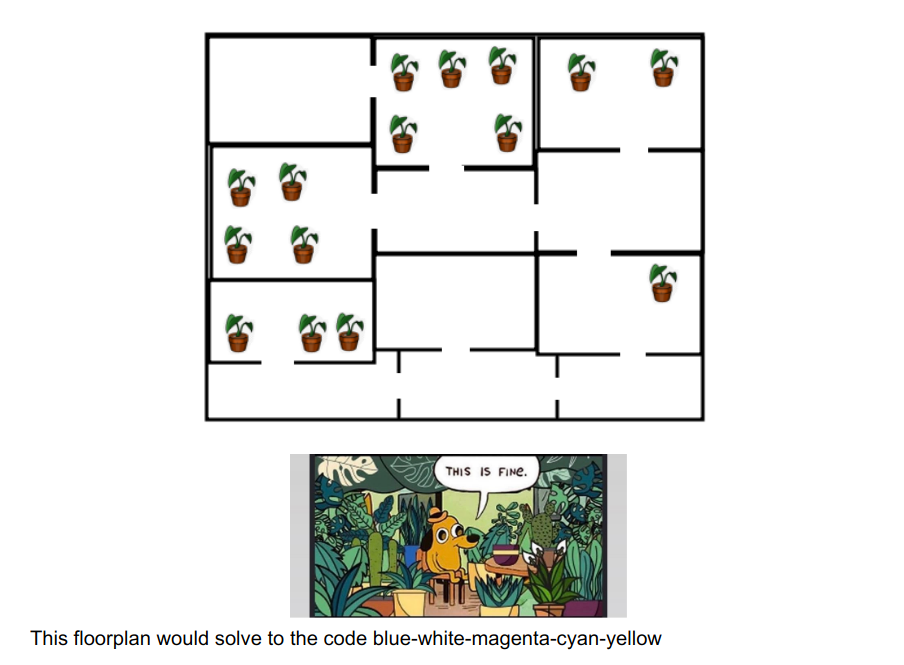

Also, here’s an early sketch of what eventually became the Floor 3 nav puzzle.

is this fine? this is fine

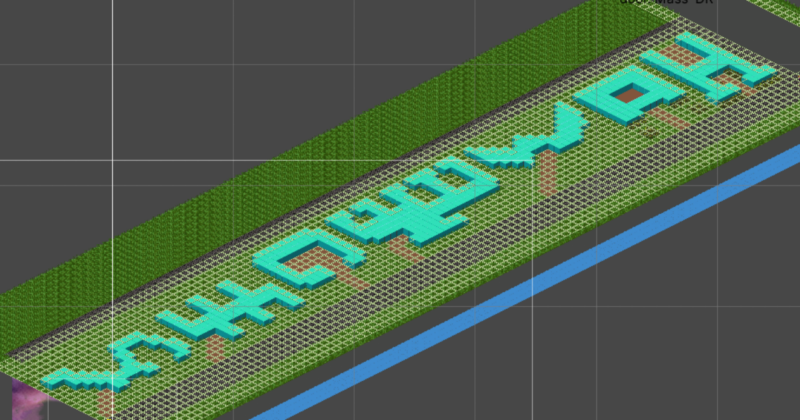

Incidentally, an entire virtual MIT was already made. During May, the MIT Minecraft server got publicized for CP*.

is ⊥IW just the mirror world of minecraft mit

Here’s some early art for the Green Building lobby in June.

pokemon vibes again

The Stata navigation puzzles began to be implemented in June as well. The final mechanics remained relatively unchanged, intended to evoke the “strange geometry” of the real-world Stata. Here’s an early sketch when the name JUICE wasn’t chosen yet, and we called it buzz, in a nod to the 2020 hunt:

buzzzzz

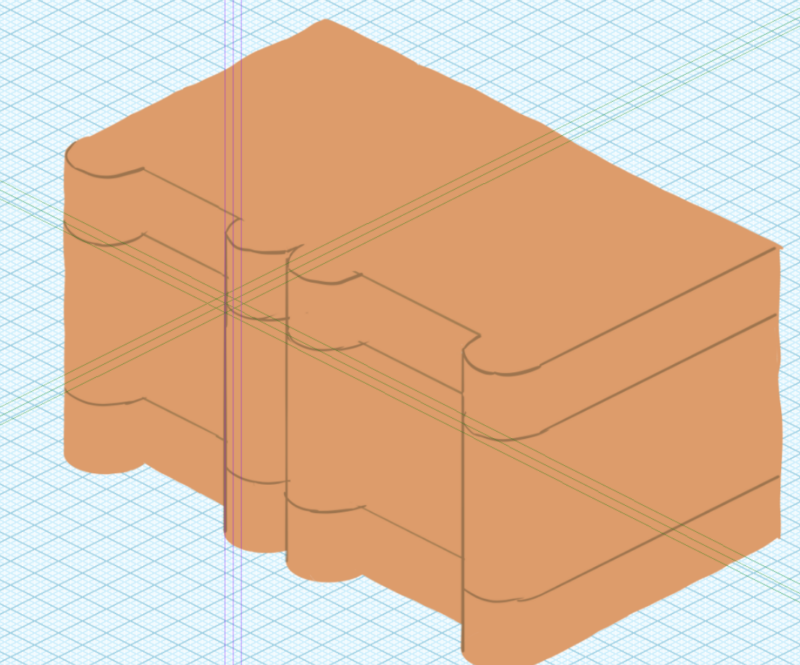

The planning for what ⊥IW.nano14 Fun fact. It was called MIT.nano in the Projection Device and all the dialogue up until December or January. began in May, and implementation began in June. It was partly inspired by Little Big Square, a puzzle game made by Colin, Jon, and Anderson, people in Galactic who made the game during their undergrad. Here are some early sketches:

In July, there was some more world building stuff. Here’s a classroom in Building 1, back when the main group buildings didn’t have doors to classrooms. The room doesn’t exist any more, although its assets were reused elsewhere.

kinda cramped classroom

The Infinite Corridor began to be implemented in July, and due to a quirk with floating point, rooms that were very far looked… weird. This was a bug that eventually became a feature, with the excuse that further classrooms were “more unstable”.

a very LARGE player

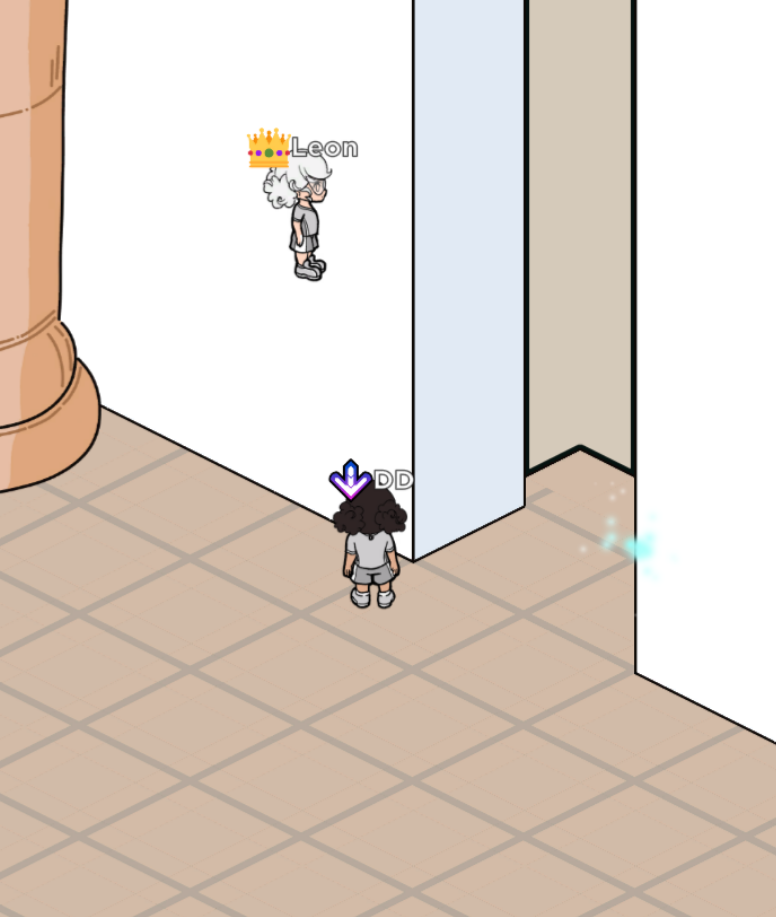

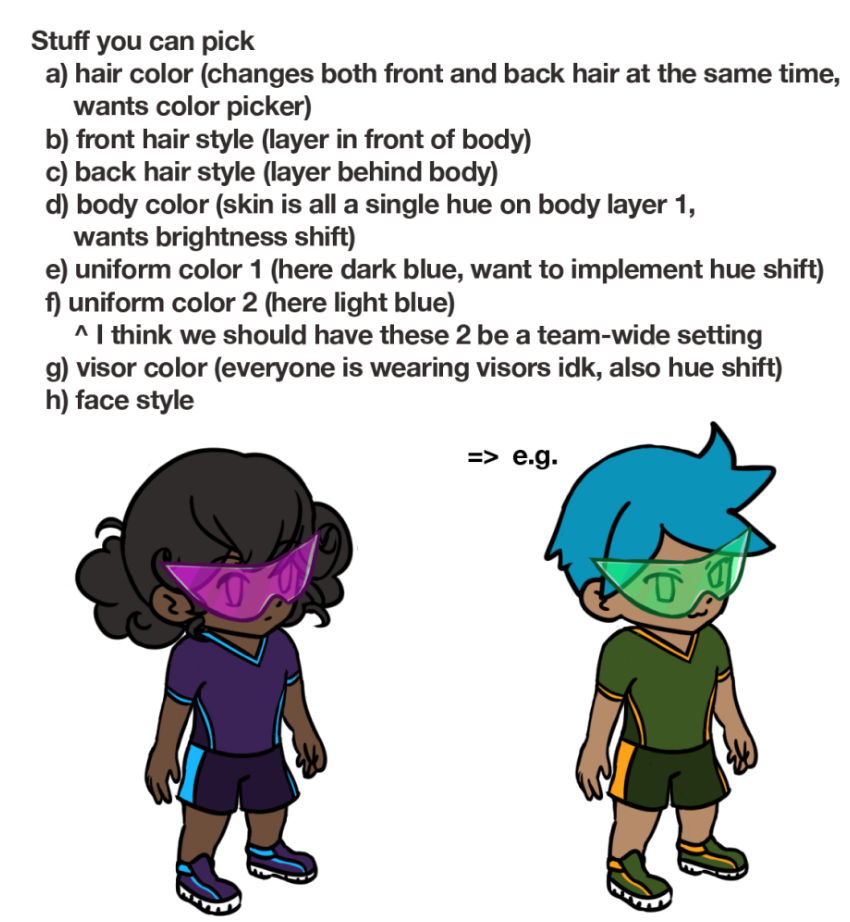

Character customization began being implemented in July, and the proposed system then was pretty close to the system now. The decision for all players to wear visors was a one-off decision based on the fact that the people in the original Galactic Trendsetters card were also wearing visors. I think the final solution ended up being some hybrid JavaScript / Silenda / Tempest / MMO client15 Silenda here is the hunt website server; I <a href="#the-copy-to-clipboard-button">talk about this more later</a>. Non-technical explanation: imagine fitting together Lego bricks with Mega Bloks with Ikea pieces, all using a screwdriver. I have no idea how it worked. solution, which is fascinating and I don’t fully understand it and I’m not sure I want to.

everyone is wearing VISORS

The Green Building was largely finalized in August. The Stata lobby was built in mid-August, and so was Lobby 7, as well as the Infinite classrooms. Building 6C, with Bars of Color, was also made, although it was eventually cut because some puzzle referred to some puzzle that referred to Bars of Color.

Here’s a short story. So you know how the Infinite Corridor has billboards? Originally these billboards were supposed to have this poster about hats. Hats were kind of a big thing art-wise, since so many members of the team pitched in and drew hats, even those who weren’t part of the core art team. Concern was raised about the poster being a red herring, so it was replaced with a different poster some time in January, but this was the poster that we saw in the Infinite for several months.

H A T. also stonks

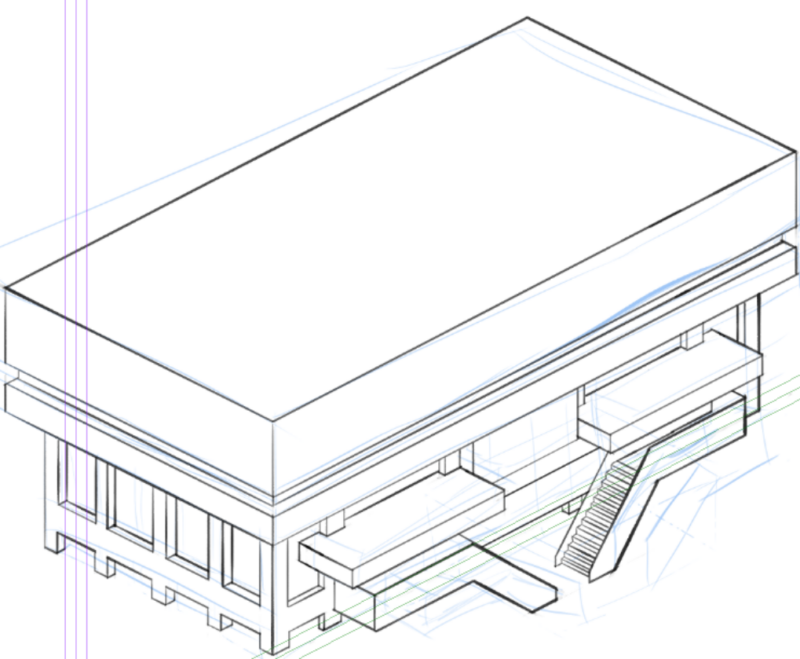

Anyway, August was the time we made the decision to run the hunt remotely. The art and MMO teams had a document outlining the amount of work they had to do left, as part of the decision, and they estimated that they could only get around 60% of the art and MMO goals by November16 Kat tells me that this estimate includes no work done on achievements, and no nav puzzle implementation for Tunnels. Wow. if they continued at the current rate of work.

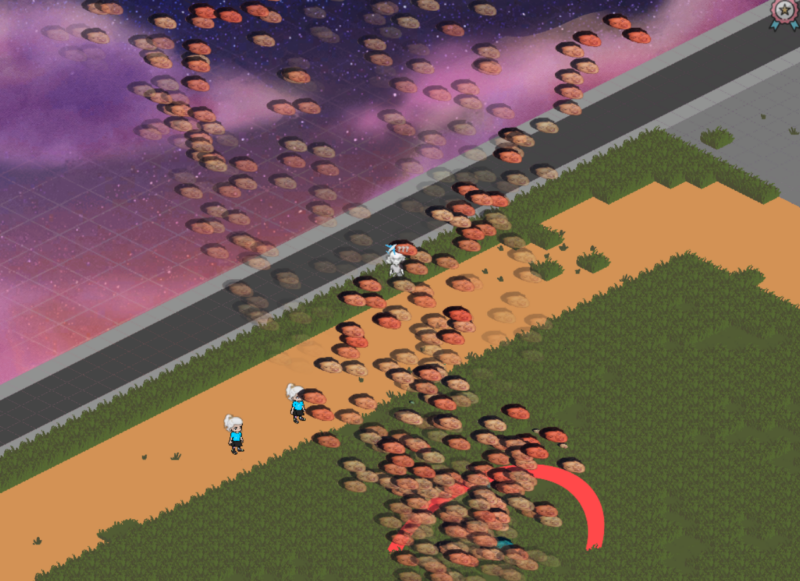

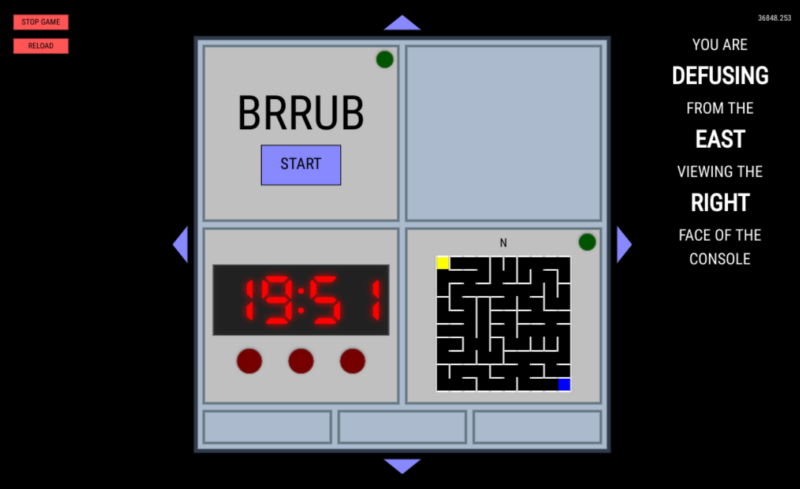

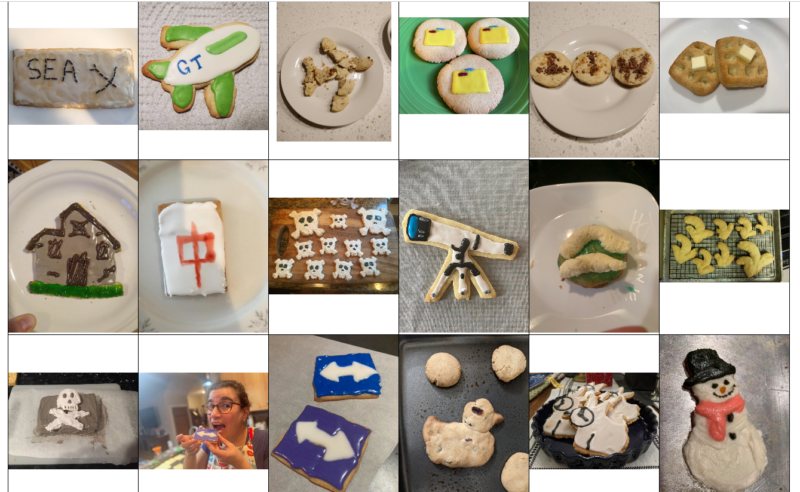

As discussed earlier, September was when the Athletics round was decided to be included in the hunt. We made the decision for Football puzzles to be MMO “achievements”, which was the name we called them internally before later changing it to “field goals”.

Some achievements have answers that are well-suited to the achievement. HYPOCERCAL is the answer to a fishing minigame, and DATA BACKUP is the answer to the Resetti achievement. NINJA BOOTS was originally supposed to be about speedrunning talking to NPCs, but is now the answer to Violet Coins in Space. Some discarded ideas were VIVIPARITY involving getting half your team in one room in the Infinite and the other half in another room, and GRADE LEVEL involving a scale in ⊥IW.nano needing people of different sizes to balance it out.

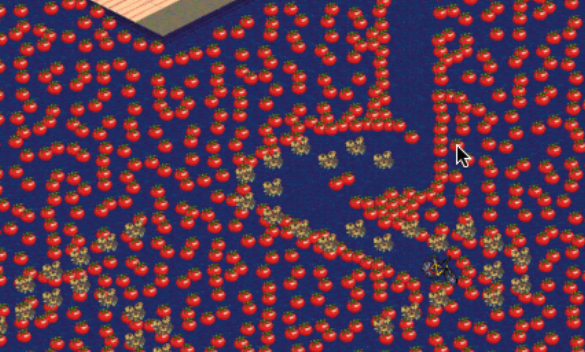

The Clusters began to be implemented in September. The original plan for the navigational puzzles were that each Clusters door had several puzzles, rather than just the single keycode puzzle that ended up happening. Here’s a screenshot of what early Clusters computers looked like.

kinda cramped in here innit

The server part of ⊥Iw.nano was implemented in September. Apparently syncing player sizes between clients was something that was particularly challenging, enough that it was still being fixed through December. Here’s some development screenshots of that area.

pretty close to final product actually

so empty without people

Some more art screenshots. September was when the walk animation was made, and DD joked that it could just be replaced with a gliding animation everywhere. There’s a picture of Dorm Row with blue blocks, already in its “facing the wrong way” position, because it looked more recognizable that way. There’s also a shot of when the Dot was made, and an earlier version of the Stata exterior.

In October there was a lot of bugfixing of stability issues and performance issues and websockets and server stuff that I don’t understand at all. A lot of these bugs were discovered during our second Big Test Solve, where we did an almost full runthrough of the MMO.

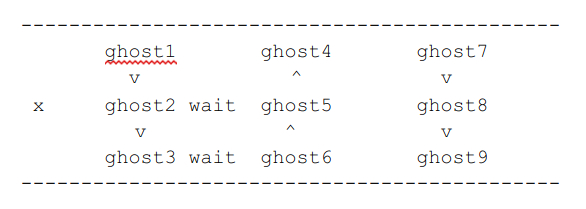

The Tunnels area was also implemented around this time. The navigation puzzle for the Tunnels was only brainstormed during October, in fact. One of the popular proposals was that you’d be on a rolling chair and you’d slide around the tunnels in a sliding ice puzzle, as a nod to the MIT tradition of chairing through the tunnels. I’m not sure how it changed to be the ghost puzzle it is now, but I think this happened in November.

In November was the first MMO race, which is discussed a bit here. We split up into two teams and used two test accounts to speedrun as fast as we could through the hunt. All the puzzles had the answer replaced with ANSWER, and the main point was to catch bugs and test puzzles. We filled two whole pages of documents with bugs. So many bugs.

Some other cool screenshots from November. There’s a beautiful rainbow Damien tornado that was unfortunately removed from the MMO, but its legacy lives on in the initial loading animation. There’s some early art for pre-fixed Stata and Random.

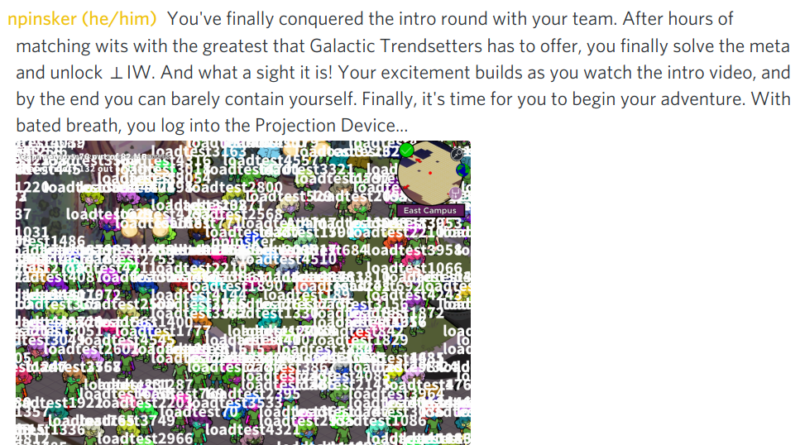

The first bit of load testing also happened in November; there’s some detail about it in this Reddit comment. At first there was trouble supporting even 200 players moving at once in the same room, because the number of movement messages apparently scaled quadratically with the number of players. The server people did some magic to make this better, somehow, and eventually we managed to have parades of robots marching through the MMO without significant issues.

Another short story. One of the games we played in the MMO was MMO Hide and Seek, which is pretty much what it sounds like, and it was a game that a lot of Galactic members liked. Trickier places like ⊥IW.nano or the Green Building were banned. But in the two big Hide and Seeks that happened, the winners were both hiding in tricky places that the players forgot to ban. The first time, in November, was in the Tunnels, back when it wasn’t even tiled yet. The second time, in December, was inside Kresge, back when the Archery event happened in Kresge17 It was eventually moved to 26-100, because we realized that not all teams would've unlocked Kresge by the time the event happened. rather than 26-100.

Here’s one thing that might be surprising. A constant problem with the MMO was z-level ordering, because of the isometric tiles we chose. Loosely, the z-level is a number that controls the order in which it’s drawn: smaller z-values are drawn behind larger z-values. This sounds like something relatively simple: isn’t it just the case that “higher” things get a larger z-value than “lower” things? Well, it’s one of the hardest challenges we faced, and it led to problems like these.

It was around this time, in December, that an entire Discord channel was made for z-ordering bugs, because there were just so many of them. It became such a meme that, in January, people joked that the term “z-ordering” was banned.

Another art thing that happened in December was drawing the buildings in West Campus. Here’s an early sketch of the Athletics area and the Student Center.

Alright, one last note. A fun fact is that 50% of the commits18 A <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commit_(version_control">commit</a> is kind of like an update made to the code. on the MMO happened in December and January, so there were a lot of things that happened in December. For example, the Tunnels entrance was moved from Killian Court to Building 13. The minimap and megamap were added in December. Building 26, and the entire interior of the Sailing Pavilion, were added in January. Reactions were very last minute. Almost all dialogue was written during that time.

It was during then that I also became involved with the MMO myself, as I’ll talk more about later. It was also then that I learned about the concept of freezing, which is a point in time after which development becomes more strict. Our original freezes were mid-December for a soft feature freeze, late December for a full feature freeze, and early January for an art freeze. I’m not sure if these quite happened, but things were definitely frozen the week leading up to hunt or so, where every single commit to the MMO was scrutinized.

So yeah. Earlier, I mentioned that the art and MMO teams estimated that 60% of the work would get done by November. I think this roughly turned out to be true, but this turned out to be not that bad because so much work happened in December. I knew crunch time was a thing, but wow that was a lot of work in a short time.

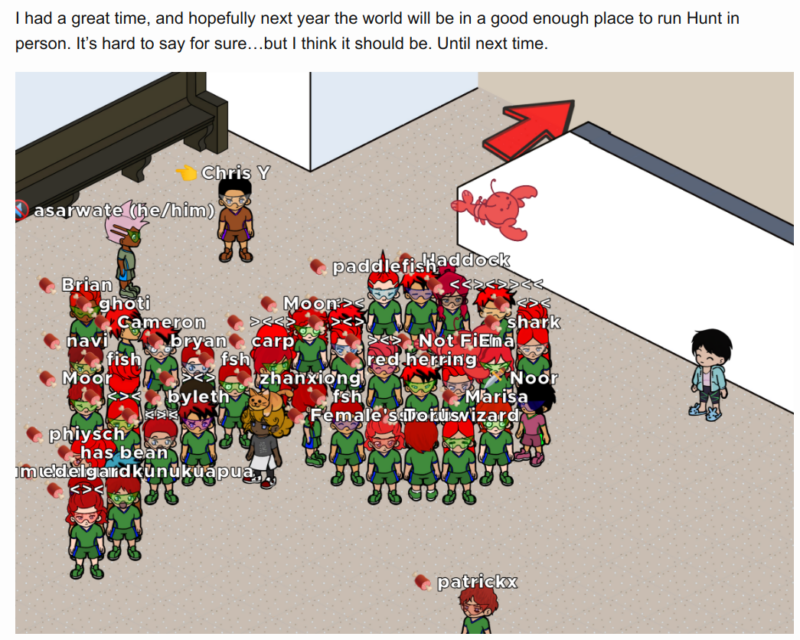

My main takeaway from all of this was pretty much the same as what Kat noted: the MMO was very much a team effort. I’ve seen this wonderful, huge project been built up from scratch and it was only possible because of the help of so many people. It’s amazing because huge programming projects like the MMO used to be completely opaque to me, and seeing this one built up from scratch was instructive and inspiring.

Developing the story

The hunt website has a recap of the entire story, and the wrap-up also has lots of interesting comments, so I won’t talk too much about the story here. I think the hunt website’s recap of the story is already pretty short, but if you want an even shorter version, it’s “Professor Yew gets trapped in the other universe, we try to rescue her only for Professor Hemlock to enter our universe instead, we swap the professors and retrieve the coin from a vending machine.”

It’s definitely the case that this story is rather different from the stories of previous Mystery Hunts. For example, this one isn’t anchored in an existing piece of media, unlike 2018’s Inside Out hunt or 2016’s Inception hunt.

Another example is that we didn’t have a “fake-out theme”. Typically kickoff skits would begin with something unrelated. For example, last year’s hunt had wedding invitations sent out during registration, and it was actually a hunt about a theme park. In 2014, the hunt was presented as a physics conference, when it was themed on Alice in Wonderland. But since the beginning of registration, we’ve always presented our hunt as a follow-up conference to 2014’s. And we played it straight: our story is very much a physics-y science fiction story.

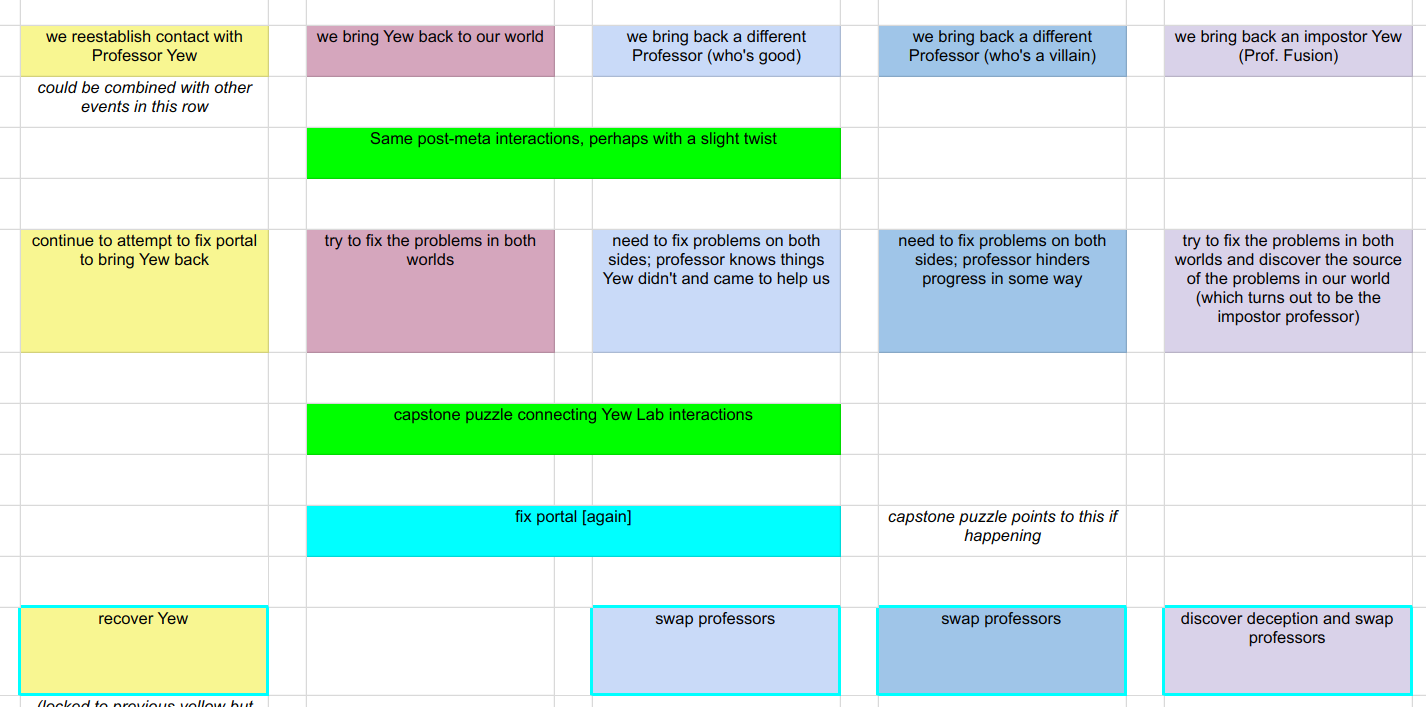

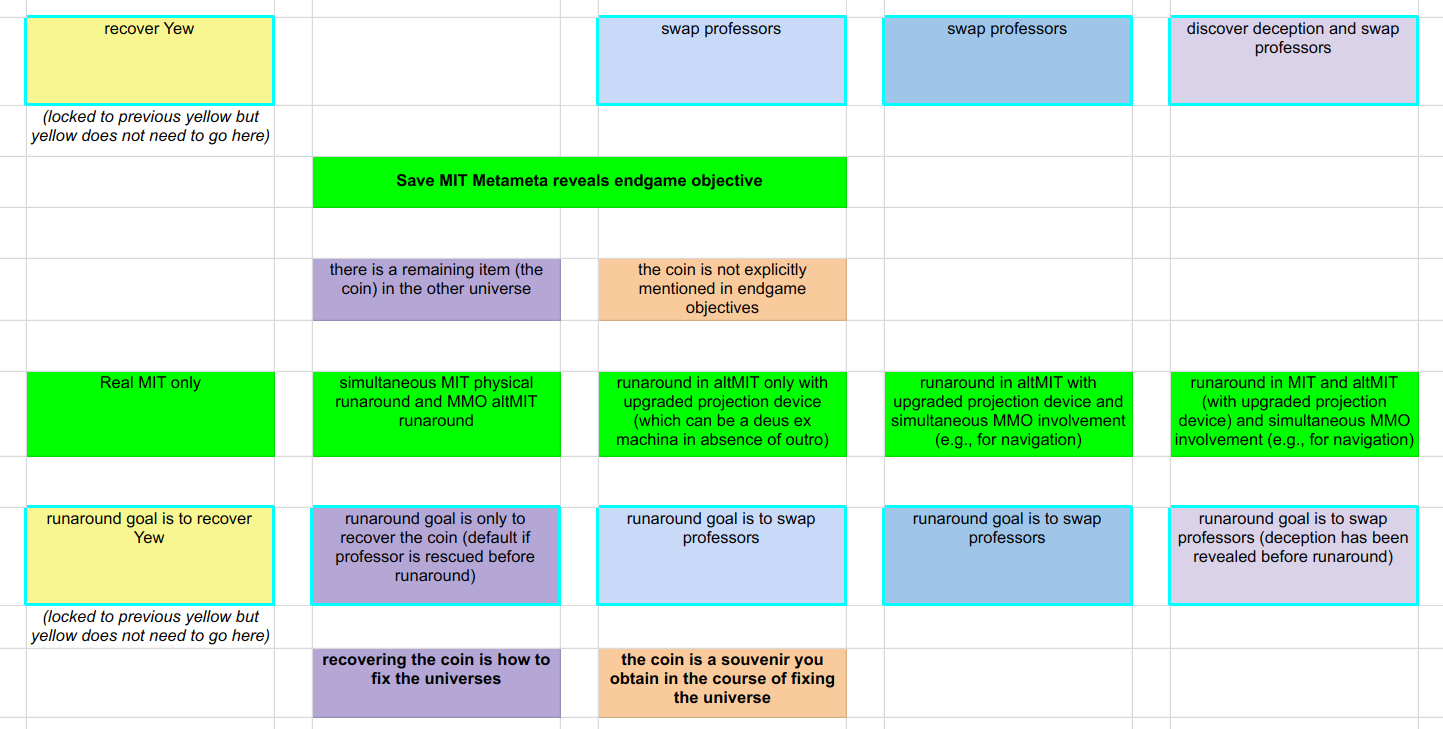

Around May or so, there was this story roadmap spreadsheet showing the possible directions the story could go. The kickoff was decided on, but many major decisions were open: what would happen in the hunt midpoint? What would be the endgame? What’s the coin? These questions were pretty much open until September.

options, options

which one to pick?

Lillian made this huge form to solicit everyone’s opinions about different parts of the story: Yew’s characterization, compelling in-story objectives, when the universes diverged, what should happen in the midgame and the endgame, how much emphasis should be put on the story, and of course, the name of altMIT. These were all finalized in late September. The rationale for the midpoint was so that we could have a character from ⊥IW who wasn’t an explicit antagonist, and the rationale for the endgame was to have a “fake-out endgame plot” of swapping the professors, when it’s actually looking for the coin. The scenes and various scripts began to be written soon after.

Galactic has a lot of people into theater, and it shows. Auditions for the roles were opened in November after some of the script had been written. They consisted of monologues; there was Professor Yew’s monologue, the post-meta interaction explanation for J and Robin, and additional monologues for other characters. Even then, the script was still very much in progress, to the point that Professor Hemlock’s name wasn’t even decided yet. Here are some role descriptions excerpted from the audition document:

Prof. Barbara Yew

She is the PI of Yew Lab. Confident and self-assured, sometimes to the point of recklessness. Mostly put-together and practical, but can be a little over the top. (Would describe herself as “no-nonsense” but no one else would.) Curious and intellectual. Science above all. This role is open to actors of any gender, but it is important that the role be portrayed as a strong female character.

J. Linden

J. is the research technician in the lab and programmed the projection device. Went to MIT for undergrad and M.Eng. Chill and cool, but strong values. Not happy about their part in almost destroying the universe. Gets to say “fuck” exactly once. Records the voiceover audio for the MMO tutorial. This role is open to actors of any gender, but the character will use they/them pronouns.

Cameron Palmer

Research associate and mechanical engineer. Has a habit of stating the obvious. Into sports, will probably get to be excited about the athletics round.

After auditions, there were callbacks, which are an invitation to do a second audition. I’m sure the theater people reading this are already shaking their heads in disapproval, but I did not know what a callback was before the auditions happened!

Final assignments for the cast were made a few days later. There was the main cast, and each of the main characters had their own understudies. They soon began their weekly rehearsals, which were quite traditionally theater-oriented. I wasn’t cast, nor was I present for pretty much any of the rehearsals, but my impression was that there was tablework,19 I'm sorry theater people, but I'm absolutely clueless as to what tablework is, even after looking it up. thinking about the character’s motivations, practicing gestures and facial reactions, that kind of stuff.

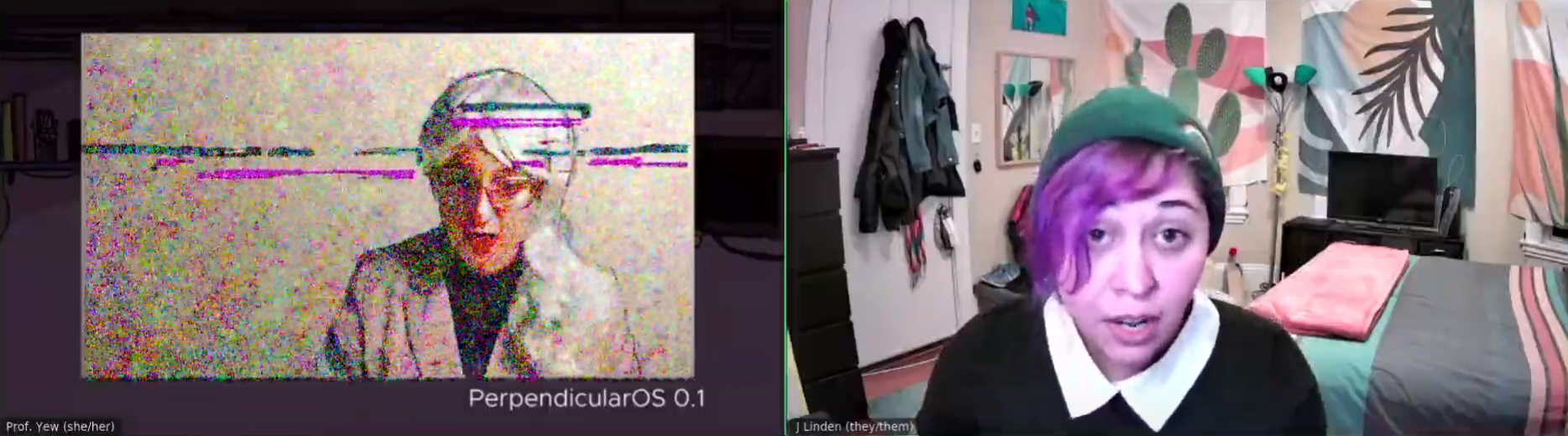

The cast developed their own set of memes through the rehearsals. For example, during the runaround, Professor Hemlock’s connection would be unstable because of the anomalies in the other universe. And during the time, Ian, who was acting as Hemlock, was having internet troubles of his own. That led to the beautiful comment from Cami that Ian’s internet was “method acting”.

Or one of Hemlock’s lines, which was supposed to be “physicists don’t typically gawk at posters, like tourists”, became “physicists don’t typically gawk at toasters, like tourists” during a rehearsal. And so toasters became a meme, enough that it got a mention in the runaround script.

The first time we all got to see the cast perform was in our third Big Test Solve in early December, where they did some scenes for us, and I was thoroughly impressed by the cast’s acting. I picked up details about the characters that I would only later learn was written in the role descriptions, like Yew’s over-the-top-ness or Skylar’s snarkiness. And to think that some of the cast didn’t even have acting experience before!

Through November more scripts were started. The kickoff and endgame had brainstorming sessions through December, and by then most of the script was finalized. Costumes and props began to be arranged after that.

A fun fact is that the cast is color coded for your convenience. Yew has white hair and a cream blazer, which is mostly because her character design is inspired by Baba from Baba Is You. Hemlock has a gray blazer, Robin wears a red sweater, J has purple hair and a purple button down, Cameron wears dark blue clothes, and Skylar wears a mustard collared shirt.

As for props: some cast members had green screens and lighting for pre-recorded scenes, the Yews had the golden record items like seedlings and CDs, and some post-meta interactions, which I’ll talk about later, also needed props. Jenna, our amazing treasurer, had a time coordinating orders for all of the clothes and props, and her dedication to that was astounding.

Dress and tech rehearsals happened the week before hunt. I participated in them because I was in charge of some of the tech for kickoff, being the member in the team with an MIT Zoom webinar license. Some of these last rehearsals were public, and it amazed me how the cast ran through the scenes in such a natural, off-book20 Off-book, meaning, without looking at the script. manner. I said earlier that I was amazed at the cast’s acting during the third Big Test Solve, and that amazement became even stronger during those final rehearsals. I have nothing but praise to the story team’s dedication to creating an immersive experience, and you should watch the recorded scenes on the hunt website to see how great it all was.

The beginning and the end

Spoilers for the final runaround.

Despite being the beginning and the end of the story, the kickoff and the runaround were some of the final things written story-wise. I was there for the brainstorming and writing for both, because I’m part of the kickoff tech and am involved in the runaround.

For the kickoff, we had our brainstorming session in mid-December, and we were playing with the idea of MYST 2021 being an online conference. It turns out that exactly one of the people who was there in the brainstorming session, Josh, had been to an online academic conference, and it was mostly a schedule of talks and sessions with Zoom links.

We tried thinking about ways to make it more social, because after all, kickoff and wrap-up are some of the few times in Mystery Hunt when hunters get to see their friends in other teams. We considered having teams give talks to make it feel more like a conference, or even having some sort of poster session. In the end, we discarded these and went with the “presenters giving a keynote” angle, since that was the way we presented it during registration: come to the keynote speech for MYST 2021!

We still managed to put in some sort of interactivity by inserting a Q&A in the middle where people could ask questions. To my knowledge, this is the first Mystery Hunt kickoff in a while that did have some sort of interactivity. We expected that the questions would be a mix between things about the story, coins and puzzles, past Mystery Hunts, and memes. So when we rehearsed the Q&A, we got a bunch of team members to submit random questions, to help prepare the cast improvise answers. We were happy when the audience ended up asking questions that we prepared for in advance, like the lab’s latest research, and “is red sus?” You can watch the Q&A part in this YouTube link.

One of the other decisions we made during kickoff was how much to talk about the Projection Device. It was a tradeoff between having teams completely surprised by the MMO, and having teams be excited about exploring an entire virtual world. In the end, we struck a balance between the two: the name “Projection Device” was dropped, although its function was only alluded to.

A few days after the kickoff brainstorm, we had the endgame brainstorm. The endgame had more details that needed to be nailed down compared to the kickoff: we needed to decide the capstone puzzles, the endgame runaround, how the story ends, and general things like how long it’d take, and how puzzly it’d be. The goals we all agreed on was that the whole endgame should be relatively short, and that it wouldn’t be aha-based; teams shouldn’t be stuck in a final puzzle like we were.

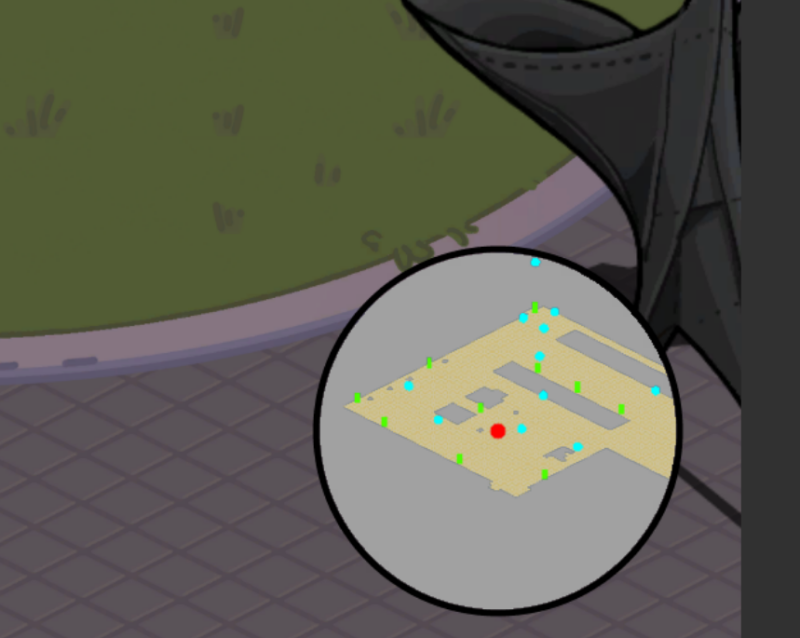

I recall that some of the proposals for the capstone puzzle involved connecting all the answers with each other using a map of the MMO, and another involved resolving the navigational puzzles in previous rounds to collect “shards” throughout ⊥IW. Doing both was even considered, in kind of a “combining Yew’s and Hemlock’s work” to lead up to the runaround. A few days later people decided that we were all too busy, so we just discarded the capstone puzzle entirely and just worked on making the runaround work.

The idea for the runaround came up after a few minutes of throwing around random ideas, on the night of Christmas, no less. It managed to fulfill our several goals for what the capstone should’ve been anyway: a puzzle that’s not too difficult, involves the MMO and the real world, and uses knowledge of previous rounds. As a bonus, it even managed to use all of the meta answers, which was something I personally love in capstone puzzles. The main idea was to take “measurements” in both the real world and the MMO to triangulate the location of the coin. Solvers would realize that the measurements are off, they’d index to find the word HYPOTENUSE, and then they’d realize they need to “combine” the measurements with the Pythagorean theorem21 <em>What if we use the fact that the universes are perpendicular?</em> Yep. The same play on the name of ⊥IW, being used yet again. to find the actual distances.

The idea of combining the two measurements with the Pythagorean theorem came first. We used all the rounds that existed in the MMO to make THIRD SIDE, and then realized we could add in Yew Labs to make the ten letters in HYPOTENUSE. The initial idea was to use only one side’s measurements to index into the answers to get the word, but we realized after testing that using the difference made more sense. Initially, the ordering was supposed to be just “whatever order we did the runaround in”, and we finagled with the ordering until we found a runaround path that made sense. But some testsolvers thought they needed to reorder the measurements somehow, so we added a reordering step involving the last digit. Personally, I think the final runaround puzzle ended up being a great end of the hunt, even if the final step of finding the coin was a bit anticlimactic.

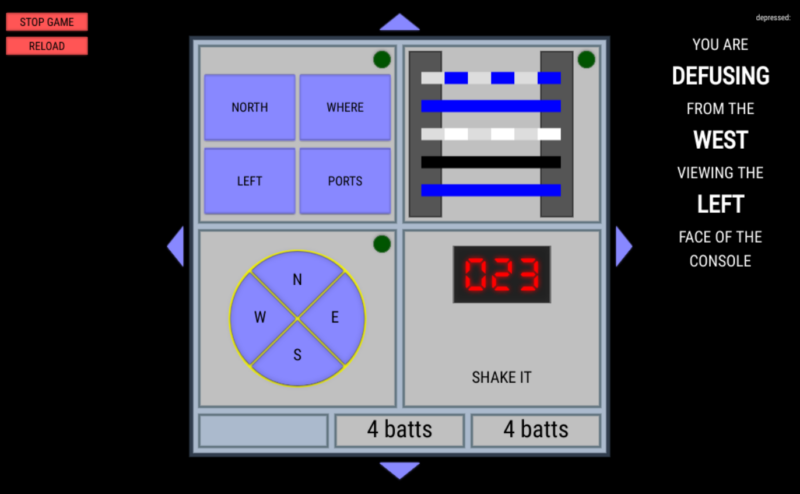

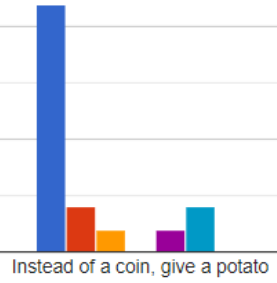

Speaking of the coin, let’s talk about how it was designed. We began thinking about it in November. A bunch of people sketched out a bunch of designs, and we had a survey to decide what the final design would be. Unfortunately, my favorite option for the coin did not end up winning.

leftmost bar is “no” by the way

Here’s a sketch of the winning coin design, and a render that Lennart made that was eventually shown in the runarounds. We kinda hoped that we’d have a real coin to show by endgame, but production was stalled so we weren’t able to. Anyway, a fun fact is that the last picture here is entirely computer-rendered: the coin, the backplate, the microscope, and the background. Lennart is a true art master.

The coins were recently delivered, so here you can view DD’s coin design in all its beautiful glory. Note the small details like the Yew Labs logo being turned upside-down to make the Hemlock Research logo. Or even the buildings along the back of the coin, with an infinitely long Infinite Corridor, or a plant-ridden Green Building. It’s a fascinating, charming design, and I love how it plays with the MIT / ⊥IW thing.

it’s the real coin!!

look look look it’s the real coin!!

Why is everyone on a video call?

Deciding to go remote

The possibility that our hunt would be affected by the whole COVID situation was something we began thinking about in March, around the time when MIT’s campus closed. We already had a document describing several contingencies we could take, with the two main options22 We also considered canceling the hunt and running the hunt as-is if it was possible, neither of which we were seriously considering. being to host the hunt online and to postpone the hunt, hopefully to run it in-person in 2022.

By June, the BDs appointed a committee to think about our “covidtingencies”, as we called it, again through the method of “whoever volunteered”. It was already becoming clear then that we couldn’t really host hunt in-person, on-campus, as we usually did. The COVID committee sent out a survey asking for everyone’s thoughts on what people valued about Mystery Hunt and initial thoughts on options, and in July there were a bunch of meetings centered on the two main options.

A meeting was held to compose a survey about the options, which was sent out to teams in mid-July. A brainstorming session about a remote hunt focused on making up for lost time within subgroups, reworking existing on-site plans, what to do with events and physical puzzles. A brainstorming session about a delayed hunt focused on modifying timelines to delay them, what would happen when interest on the writing team changed, possible interim events, and when the decision about the 2022 hunt would be made. The art, story, and MMO subgroups had meetings to talk about what would happen in both options.

Then there were lots and lots of documents written. There was a document about proposal, detailing its specifics and what would be adjusted. There was a document summarizing all the content from the survey. We also had another document summarizing pros and cons for the two proposals. And then there were opinion pieces from members of the team about both proposals. There was, needless to say, a lot of discussion, and all sorts of people on the team who supported the two proposals to different extents. I was on the fence myself, but leaning towards postponing the hunt.

The COVID committee, in early August, sent out these documents to the team and asked for comment. They also scheduled and led a team-wide discussion to talk about the proposals, and then sent out a vote (through STAR voting, yes). Then the voting closed, and the BDs announced the results: running hunt remotely won by a considerable margin, and that’s what we would do.

Two thoughts about the whole thing. First, I think the committee did a really good job. They set out a clear timeline and framework for making the decision, they collected feedback from all the relevant stakeholders, and their communication was clear and supportive: we’re a team, none of this was what we wanted, we’re here to have fun and be creative, it’s okay to take a break. And the “we’re a team” part is something I really, truly felt at that time, especially in the middle of such a tough decision.

the reaction here is a cuttlefish emoji