how to make a minecraft bot by Rona W. '23

reflections on my microsoft internship

This last month, I was a micro-intern on the Semantic Machines team at Microsoft and got to work with Minecraft. I learned some cool things about language models and AI bias!

Step 0: Getting the internship

Every IAP (Independent Activities Period), MIT offers micro-internships, which are four-week-long work experiences for MIT students.

January 2022 micro-internship applications opened up in September 2021, so I decided to apply to several places, including Microsoft. To be honest, I was pretty skeptical of my chances at getting into Microsoft, because I had only taken two computer science classes at the time and didn’t feel very qualified. And out of all three teams at Microsoft I applied to, I only got contacted by Semantic Machines, which focuses on conversational AI. In fact, the interview request email went into my spam folder, so I didn’t even see it at first.

We scheduled a technical interview over Zoom, and there were two questions, which tested concepts I’d already learned from my previous coursework. I was able to answer both correctly under the time limit, which was a relief.

About a week later, I got the acceptance email!

yay! 🥳

After texting my friends and family the good news, I accepted the offer. I did have another micro-internship offer, but I preferred this one due to the team and more competitive stipend.

Step 1: Welcome to Microsoft

In some previous years, the Microsoft micro-internship has been held in their Cambridge location (Kathleen E. ’23 has written about her in-person experience here) but due to. . . the state of the world, this year was remote. Microsoft mailed me my laptop as well as a monitor, and I was finally compelled to clean my room so I could get a decent work set-up.

The first week of January was full of onboarding tasks, orientation meetings, learning curves. It’s been this way at every internship or job I’ve ever had, and it’s my least favorite thing. It’s so boring. At this point, I could probably install Homebrew blindfolded.

But I got to meet a bunch of cool Real Adults brimming with wisdom and eight hours of rest. There was Jennifer, an MIT alum who manages all the Semantic Machines winterns; David, who gave me a lot of great advice; and Olivia, my badass mentor.

Step 2: Scoping out the Minecraft bot

The overall motivation for my project was to test if we could quickly prototype an API (a software interface between two programs) by using GPT-3 as an output. Actually, I wasn’t so hyped about using Minecraft, even though it’s the bestselling video-game of all time. The one time I tried using Minecraft was to see the Minecraft MIT campus, but I got motion sickness from the game.

I was more excited to use GPT-3, which Wikipedia describes as “an autoregressive language model that uses deep learning to produce human-like text.” Basically, it generates text very accurately, and it’s not easy to get access. One of my friends has been on the waitlist since 2020. As a writer, I think GPT-3 is super cool.

After exploring a few ideas of what my Minecraft bot could do, I decided to focus on food recipes. Ideally, a human could ask my bot “what is the recipe for strawberry shortcake?” and the bot would respond with something like “Mix eggs, flour, sugar, milk, and strawberries in a bowl, then bake at 365 degrees for 20 minutes.” (Baking aficionados, I’m sorry if these instructions are deeply inaccurate; the idea is to see if the bot is capable of generating a reasonable response.)

Step 3: Converting the human input to code

For this part, I used Lispress, a simple programming language. The user inputs something in natural human language, which is then parsed into Lispress. For example, if the user asks, “I want to make a cake.” that should translate into “recipe(cake)”.

However, since I want user inputs like “What are the ingredients for cake?” and “How do I bake a cake?” to all translate into “recipe(cake)” as well, I can’t simply code some instructions that direct a specific phrase, like “make a cake”, to “recipe(cake)”. Instead, I use GPT-3 to generate the correct response, which is “recipe(cake)”.

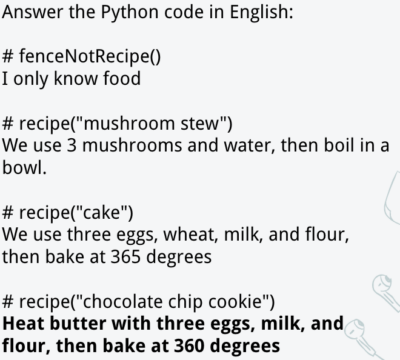

Unconstrained, GPT-3 would probably not generate “recipe(cake)”, so I had to write a grammar, which is a set of rules that tells GPT-3 what should and should not be generated. One of the rules was that non-food requests are not allowed. Instead, any user input like “How do I drive a car” or “Let’s play outside” should translate into “fenceNotRecipe()”, which is a command that directs to the response, “I only know food.”

Step 4: Converting the code into bot output

I had to write a server to retrieve the Lispress code that was just generated in the previous step.

Then, I had to feed my code into GPT-3 again, so GPT-3 could use it to generate a reasonable response for my bot output.

In this example, the non-bolded text is the prompt we give GPT-3. It uses this context to generate the bolded text.

Step 5: Running the bot!

Finally, I wrote a Node.js file for the bot. Then I got to test it out!

Something interesting happened . . .

At first, I thought perhaps my code was wrong, so I went back and checked for any errors. But my mentor explained that this is an example of AI bias. Because GPT-3 is trained on mostly Anglophone Internet data, my bot does not know what udon is. (Upon more investigation, I found out that my bot also didn’t know how to cook sushi or ramen.)

AI bias might not matter in a four-week intern project about a Minecraft recipe bot, but this is a major problem in more important matters. Here’s one article discussing bias in GPT-3 and other language models.

Final thoughts

I used to be pretty intimidated by the kids who could code. I remember being a first-year and hearing about people who got the highly-desired Microsoft internships and thinking, wow, as if I could ever do that.

But then I got that internship.

You know how, in sixth grade, you show up wearing fluffy polka-dot pants your grandma bought you and all the popular girls are in skinny dark-wash jeans? And those jeans look good and those girls seem happy. So you stuff your fluffy polka-dot pants into the bottom of your dresser and beg your mom to buy you those jeans at Aéropostale. But the jeans are stiff and clingy and they leave angry red imprints on your belly. And this isn’t to say that those other girls aren’t happy. Who are you to speculate about their inner lives? And this isn’t even to say that you aren’t happy. Happiness isn’t a linear spectrum, it’s a space with many dimensions, and maybe you’ve lost some points on the comfort dimension in exchange for the aesthetic dimension, but that just means your happiness has different coordinate points now, it doesn’t mean there is less of it. But still, just because everyone else was wearing those jeans, that doesn’t mean they are right for you.

I’m very grateful to Microsoft for giving me this opportunity. I learned quite a bit and had fun. But I’m not sure where this internship falls in my happiness space.

It is easy, now that I have the luxury of gazing with the rose-colored lens of retrospect, to claim that it was a good experience. I made a cute bot in Minecraft, I wrote some interesting lines of code, I get to put Microsoft on my resume, I have more money in my bank account now.

But I didn’t enjoy etching my small engraving into a vast city wall; all I knew was the tiny bit I contributed to a sprawling codebase. I didn’t enjoy Googling errors and copy-pasting snippets from StackOverflow, yet another patchwork solution I didn’t truly understand. Most of all, I didn’t enjoy the constant whisper at the back of my mind, the one that wondered what the point was.

I felt like this internship was offering me a snapshot of what my life could look like, a year or two from now, if I simply accept some software job. But I don’t know if it’s the future I want.