All I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten (and at MIT) by Elizabeth Choe '13

[Disclaimer: Not my last post! I’ve still got one more in me after this one. :)]

The other day I was hanging out with one of my best friends from high school when we got into a heated argument about the value of an undergraduate college degree. My friend, who I love very dearly and consider my own flesh and blood, is very bright but has always hated school because of its arbitrarily bureaucratic hoops. To give you an idea of what he is like, he taught my little brother (who was four at the time) to respond with “Stick it to the Man” when people asked what he wanted to be when he grew up. I reached for the right words to validate the way I had spent my last four years halfway across the country. Essentially, I was trying to stop him from dropping out of college.

Without trying to belittle the diploma that I’d received less than a week before, he posited that many talented kids would be better off (and might contribute more to the world) pursuing projects or companies or whatever business endeavors that they were really interested in instead of enduring the confined walls of a university and its limiting course requirements. Pullling a Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs or one of these guys, if you will. Presented with a hypothetical situation in which 18-year-old Elizabeth and 22-year-old Elizabeth were both gunning for the same job, he said he’d regard both equally, because while 22-year-old me has the diploma, the 18-year-old me that he knew had the drive and tenacity that would’ve figured out a way to succeed. At that point I had to stop yelling at him and just grin uncontrollably, because the 18-year-old me was obnoxious and kind of an asshat, and it was a miracle that he and my other friends ever put up with me, and it would be an even bigger miracle for a full-time employer to do the same. But it also horrified me, because suddenly I was faced with presenting a defense of all the ways I had changed in the last four years and all the things that college had given me and I was at a loss for words. You might be incredulous at the fact that I hadn’t been reflecting on these things during my last few weeks at MIT, but I wasn’t thinking about these things. I was frantically packing, moving things into storage, saying goodbye, watching movies with friends who I won’t see for indefinite periods of time, enduring the wildly craptastic weather during graduation, and in denial that the ‘Tute was kicking me out, and that with this piece of paper, society saw me as somehow qualified to be a grown up and do grown up things in the grown up world. What did I learn at MIT?

(We shouted at each other some more, banged our fists on the table, disturbed other people in the restaurant, and then gave each other big hugs before saying goodnight, the issue left unresolved.)

A couple days later, I was flipping through old photo albums (because I am actually that nauseatingly sentimental of a person and do that crap everytime I go home, and because I was looking for pictures to use in a Father’s Day card) and came across pictures from my kindergarten graduation. Evidently my mom is equally sentimental because she had kept everything they gave us during the graduation ceremony (yes. We had a ceremony. And a rainbow cap and gown color theme.). One of those things was a copy of Robert Fulghum’s “All I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten,” which has become a standard for coming-of-age celebrations almost ubiquitous as Vitamin C’s “Graduation”. And it got me thinking about what I learned in college…

All I Ever Really Needed to Know I Learned in Kindergarten by Robert Fulgham

Most of what I really need to know about how to live, and what to do, and how to be, I learned in Kindergarten. Wisdom was not at the top of the graduate school mountain, but there in the sandbox at nursery school.

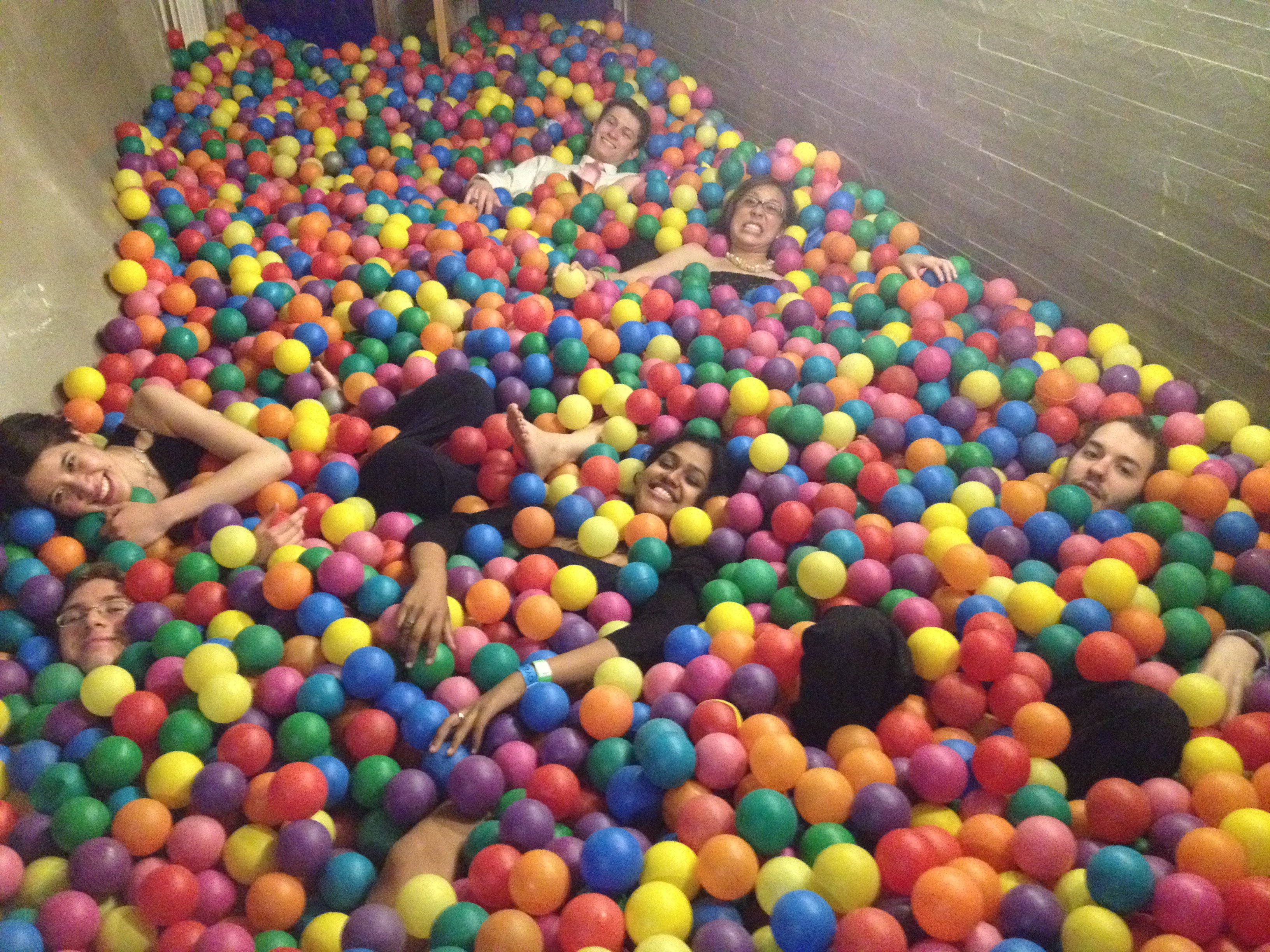

Or, in the ball pit in Simmons Hall, originally built as a “Meditation Room” and where we held our Senior Ball[pit] “afterparty”.

These are the things I learned: Share everything.

People experience some pretty heinous living situations in college and early adulthood. Others get absurdly fortunate and find a home to share with people. I, rather undeservedly and extreme luckily, fell into the latter category. I met my freshman roommate, Sneha, when we serendipitously peeked at each others’ rooming survey (we happened to be standing next to each other), only to notice that the other shared living habits similar to people at least three times our age (“You go to bed early? You don’t like noise? What the WHAT?!”). We shared the same room with each other for four years. I shared a bathroom with guys and I shared a kitchen with hallmates who never cleaned their dishes (I admit I’ve committed the eggregious offense of “soaking” my bowls numerous times). I yelled at people to shut up (using choice words that I cannot put on the blogs) and I stayed up with people for no reason other than to derp in the hallways and enjoy their company. I shared a home with over 300 people and I learned to compromise. I got better about being tidy and trying to be less hypocritcal. The family I had in our home of Simmons Hall was generous and I can’t say I always returned their friendship as much as I should have, but at the very least, I learned how to be a better friend.

Play fair.

Five years ago I asked my MIT interviewer what his favorite part about the Institute was, and he told me that he loved that it was as close a thing to a meritocracy in this world as they get. I lived in this meritocracy for four years and it gave me one of the things I will treasure most – toughness. It made me earn everything, it made me learn to take criticism and to build back up from it. That isn’t to say that MIT doesn’t recognize that some people get stuck playing the game of life on a much harder level, and try to level the playing field accordingly (I can’t remember where I heard it phrased like that, but I’ve been partial to it ever since). But I’ll be damned if that isn’t being fair. None of us caught breaks because we were girls or came from interesting backgrounds or were rich or poor or whatever. We had to prove ourselves constantly. I don’t think it was always the healthiest thing, because folks start equating their self-worth with a very narrow definition of success, and sometimes it meant that there were some real assholes floating around this place. But because it was a meritocracy, I spent the last four years having no illusions of grandeur in a very, very good way. Teaching twentysomethings not to feel so entitled to everything? I’m not sure if it had that effect on everyone here, but it sure as hell did for me.

Don’t hit people. Put things back where you found them. Clean up your own mess.

My room at home the summer before college and my room at school packing up after my first semester.

Literal messes: I, like most of the students here, moved myself into my dorm during freshman orientation and had to go through storing everything on my own every summer. You know what builds character? Having to pack up all your crap on your own. It also makes you have a much more critical eye when amassing purchases.

Figurative messes: When poo hits the proverbial fan, it may be beyond the scope of what Mom and Dad can do to help. Maybe I just lived a very fortunate life to not have to deal with such poo until I left home, but I encountered this in college and had to figure out how to clean up my own messes. Better I did it in my early twenties than later…

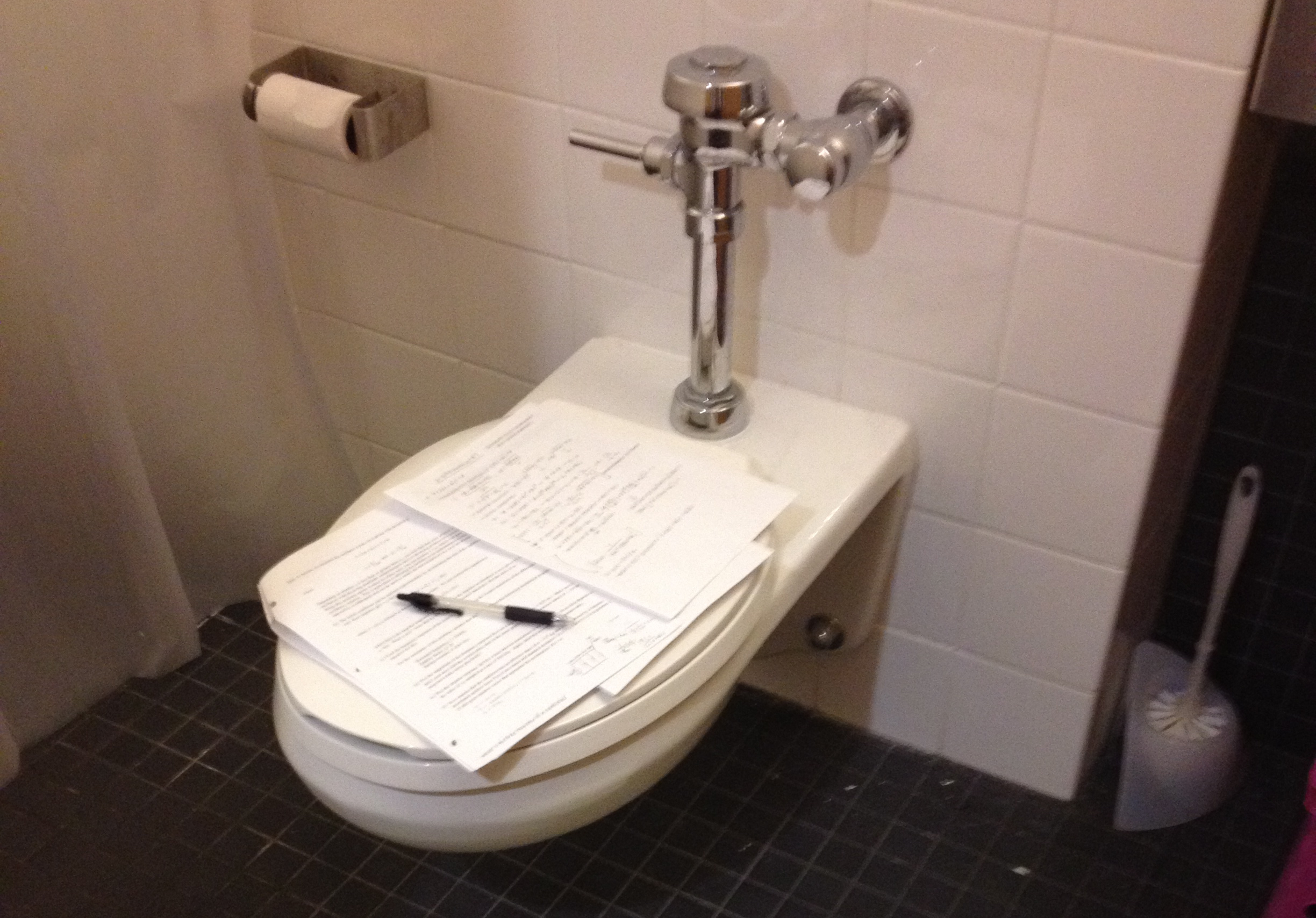

Wash your hands before you eat. Flush.

Somewhat unrelated, but here’s a shot of our bathroom when Cambridge experienced a freak power outage this year (the only one I’ve ever experienced there). MIT’s backup generators go straight to the labs, so Simmons was left without lights, save for the emergency ones in the stairwells and… bathrooms? Power outages can’t stop problem setting!

Warm cookies and cold milk are good for you.

As are Nathan’s homemade rosewater buttercream cupcakes and Russell’s homemade pizza.

Live a balanced life. Learn some and think some and draw and paint and sing and dance and play and work some every day.

A few weeks ago, Hamsika asked me what the biggest thing that changed about me since coming to MIT was, and I told her that I’d become much less ambitious. Again, as with all of my experiences, I can’t claim it to be indicative of that of the rest of my classmates, but she seemed to be in agreement. I worked really hard at MIT (most of us did), and it was amazing to be constantly surrounded by people who were driven and cared about things (people throw around the word “passion” a lot, but let’s face it. It’s really just caring about something). People at MIT don’t really half-ass things (most of the time), which also made it an incredibly exhausting place to be sometimes. I never took for granted being in the company of people who care, regardless of how grating or tiring it got, but I also started valuing and appreciating things like leisure and side projects and meaningful relationships a lot more. It meant I had to prioritize things – some projects were left unpursued, some friendships suffered, MANY blog posts were left unwritten – but in the end I sort of figured out what made me happy and fulfilled and sane, which is something I’m very glad to know.

Take a nap every afternoon.

Sigh. I’ve never been a napper. I was that weird kid in preschool who stayed awake during naptime, sitting on my cot waiting for the others to wake up. Unfortunately, MIT did little to change that for me, though my friends never seemed to have the same problem.

When you go out into the world, watch for traffic, hold hands, and stick together.

That’s the thing about MIT. We go through everything as a team – working, struggling with homework, comforting each other when it’s 4 am and we’re still not done with a pset, celebrating birthdays at midnight (even though it was never a surprise), and grinning so wide at others’ accomplishments and successes they might as well be our own. (Couldn’t have said it better, Hamsika. Read the rest of her last post here!)

Be aware of wonder.

I loved many things about this school, one of them being that there were days where I’d walk down the Infinite Corridor and just smile to myself, in awe of everything that was around me. I knew next door, someone was making something that has never been made or discovering something that had never been known. And on top of that, I had the priviledge of spending four years experiencing those moments in class, four years where my primary obligation was to learn about the world. It was incredibly humbling. Wonder isn’t a a sparkly concept emblazoned on a Lisa Frank backpack (although I’m pretty sure I owned one in first grade), but a reflection of respect for the universe as we try to wrap our tiny minds around it. Our world is messed up, but it is also overwhelmingly beautiful and simulatenously small and expansive and I feel so lucky to have what sliver of knowledge I do about it, and hopefully I’ll use it to make it a little better. Ironically, it became easier to lose sight of this the further I got into my studies. I met people who seemed so lost in the depths of their research or work that they didn’t always seem to grasp its impact on a higher, societal level. But there were enough people at MIT who nudged me out of cynicism when I needed it most.

Remember the little seed in the plastic cup. The roots go down and the plant goes up and nobody really knows how or why, but we are all like that.

“I can’t wait to get out of here. I am willing to forgo the rest of the summer to get to Boston sooner.” I remember saying these words to someone in July of 2009, right before I left my hometown (where I’d lived my whole life) to go to MIT. I was in such a hurry to leave, not realizing just how deeply my roots had been planted. Ripping them out totally backfired on me. I missed my family, my friends, being able to see the stars at night, Shakespeare’s Pizza, and Ninth Street more than I ever thought I would. People are more than the little seed in the plastic cup – we can plant roots in multiple places, and instead of pulling us in different directions and further into the ground, they only help us to grow taller. You don’t have to uproot yourself to go on an adventure, as my 18-year-old self had mistaken. Deeper roots only send you further than you could have ever gone on your own.

Goldfish and hamsters and white mice and even the little seed in the plastic cup – they all die. So do we.

Of course, this one is the most difficult to write about, especially because death’s inevitability doesn’t make it easier to process when it comes too soon and too unjustly. I’m not sure that I or any of us will fully come to terms with the loss of a life, whether it makes national headlines, as so many did this year, or is a quiet individual experience of mourning; whether it is that of a complete stranger or someone you shared your life with. Life is so precious, and I wish we all (myself included) didn’t need death to put things in perspective, to remind us that there are always reasons to be joyful and thankful in the face of problem sets and deadlines and the millions of excuses to be miserable. Death is not an end, and these beautiful people proved it. Live well, live selflessly, and live fully, and your life will be an example for others to do the same, even after it comes to an end.

And then remember the book about Dick and Jane and the first word you learned, the biggest word of all: LOOK. Everything you need to know is in there somewhere. The Golden Rule and love and basic sanitation, ecology and politics and sane living.

At the end of my MIT interview (which, for the record, went very, very, objectively TERRIBLY), my interviewer told me that MIT had everything I could ever want, but that no one would give it to me. If you needed help, if you wanted to work on a great project… it was all there, but you had to look for it yourself. Job opportunities, a good night’s rest, friendships, clean laundry, happiness – you had to make these things for yourself. I was very lucky that during these four years, many of the things I needed were right within arm’s reach, as MIT was an environment that facilitated locating these things pretty nicely. As I depart the physical location of MIT and the life-niche of college, there are days where I am bona-fide-terri-fied of what life will look like out in the real world. A real world where I can’t just walk up three flights of stairs to find a hallway full of friends, where I can’t make a real life light-saber just because I have access to machinery that can mill the parts (though let’s be real, I never took advantage of that), where I can’t pop into an advisor’s office for life advice. But I think I’ve managed to fumble together an assemblance of a life, and I know that everything I need will still be out there, even if it is harder to find.

Think of what a better world it would be if we all – the whole world – had cookies and milk about 3 o’clock every afternoon and then lay down with our blankets for a nap. Or if we had a basic policy in our nation and other nations to always put things back where we found them and clean up our own messes. And it is still true, no matter how old you are, when you go out into the world, it is best to hold hands and stick together.

To my friend (if you are reading this),

If you really want to drop out, and if you really think you’ll make more out of your life doing something other than going through our admittedly-less-than-ideal American university system, then I say… go for it. I will love and understand you no less. Evidently all I ever really needed to know, and all I gathered from a rather decent institution of higher learning, were things that I should have learned when I was four years old. And on top of that, college (or kindergarten, for that matter) didn’t teach me everything. I did not learn how to refinance a house, fix a flat tire, enjoy eating dinner by myself, or stop using parenthetical remarks so excessively. College is not for everyone (though you have to admit that, for better or worse, we are living in a society where it is becoming increasingly more difficult to enjoy a higher quality of life without a diploma), and MIT is not for everyone. There were times I was miserable here and you and many, many others would have endured a misery far greater than mine. Not because you couldn’t handle it, but because you would not necessarily find the things that made me happy and fulfilled worth tolerating the less-than-desirable qualities of this place. But I did get a lot out of being here, a piece of paper probably being the least important on the list. I guess what I’m trying to say, albeit super long-windedly, is that my experiences have been very personal to me. Yours have been, too. And that’s okay. We are different, and so a path that best suits us will look different. But I would – in a heartbeat, without an ounce of doubt – take 22-year-old Elizabeth over that snothead you used to get into shenanigans with back in high school. And being here made all the difference.

(I would DEFINITELY hire 22-year-old Elizabeth over 4-year-old Elizabeth.)