MIT Festival of Learning: Lightning Round by Yuliya K. '18

six eminent faculty on educational technology innovations

The Festival of Learning is an annual event organized by the MIT Office of Digital Learning around the idea that we need to bring technology and pedagogy together for effective learning. I blogged an overview of the first Festival here. This post is the third of a series of three posts about this year’s Festival. It features summaries of six short talks by eminent faculty on the latest educational developments in MIT classrooms. Read the first FoL post about Woodie Flowers’ “Nerd Epistemology” here (Prof. Flowers is the co-founder of the FIRST Robotics Competition and MIT Professor of Mechanical Engineering). Read about the FoL Expo, showcasing fascinating educational developments at MIT and beyond, here.

Note: this post was originally published on the MIT Office of Digital Learning blog here.

This year’s Festival of Learning featured a ‘Lightning Round’ of six eminent MIT faculty sharing their experiences leveraging and exploring new technologies toward the goal of innovating teaching and learning at MIT. What follows are summaries of each presentation. But first, short previews and links to videos of the talks:

Anette “Peko” Hosoi (Course 2 – Mechanical Engineering) introduced the amazing NEET (New Engineering Educational Transformation) program for MIT undergraduates, which is a new venture to encourage students to learn about new machines, engage in different modes of thinking, and practice problem solving by completing real engineering projects, such as building a gut on a chip.

Shigeru Miyagawa (Course 24 – Linguistics & Course 21G – Global Studies and Languages) demonstrated his fascinating approach of studying Japanese history through visual materials and discussed the impact and process of creating an online course for 21G.027 Visualizing Japan in the Modern World.

Ian Waitz (Vice Chancellor, Course 16 – Aerospace Engineering) updated us on the Institute-wide efforts to reshape the first-year undergraduate experience at MIT, which include leading a for-credit project-based design course open to all students, 2.S991 Designing the First Year at MIT.

Barton Zwiebach (Course 8 – Physics) talked about reshaping the undergraduate quantum mechanics course sequence using the latest online tools.

Jeff Grossman (Course 3 – Materials Science and Engineering) shared his experience using take-home mini-experiments, or “goodie bags,” in 3.091 Introduction to Solid-State Chemistry, a Chemistry GIR (General Institute Requirement), as inspired by a 6-year old’s birthday party.

Thomas Kochan (MIT Sloan School of Management) shared his favorite thing at MIT, which is 15.662 Shaping the Future of Work, a blended online and on-campus course that allows Sloan MBAs to negotiate a new social contract for the workforce with workers from around the world.

Anette “Peko” Hosoi

NEET: the Answer to “Is Engineering Education Obsolete?”

One and a half years ago, Anette “Peko” Hosoi, Ed Crawley, and Babi Mitra—along with MIT faculty, students, alumni, employers, and consultants—began thinking about the future of engineering education. They were most inspired by words from Sugata Mitra’s TED Talk: the format of our education system lecture went obsolete with the invention of the printing press.

Here’s an example of why that’s true at MIT. Below are two planes from different times in history. For the machine on the left, the shape is dictated by aerodynamics. It has a gas turbine engine and requires a pilot. The machine on the right is stealthy—its shape dictated by electromagnetism—and is the first autonomously driven and refueled Navy drone. Students in the undergraduate Aerospace Engineering program at MIT are only prepared to build one of those planes by the time they graduate, and it is not the most recently designed. This is unfortunately true for engineering students of all disciplines. So how do we prepare students to build new machines rather than the machines of the 1950s?

This is the motivating question for the NEET (New Engineering Educational Transformation) program for MIT undergraduates. There are three main purposes behind the NEET curriculum: learning about new machines, engaging in different modes of thinking (e.g. collaborative, critical, leader etc), and practical problem solving (or Mens et Manus, MIT’s slogan).

NEET students enroll in the program in their sophomore year and immediately get started on their first project, such as, for example, building a gut on a chip—a living machine. Along with their group project work, students engage in increasingly complex humanistic arguments and explore classes across disciplines, building up a strong academic and critical thinking foundation for their capstone senior year NEET project. Along the way, students also get to engage with local experts in the industry and with faculty—discussing career and research options, class recommendations, and major selection. Students will often UROP with some of the faculty as well.

At the end of their journey, NEET students receive certificates for completing the program, along with their regular undergraduate degree. But even more importantly, they reap the advantages of having an informed choice of major, practical experience in their field of choice, and connections with leaders in that field.

For more questions about NEET, visit neet.mit.edu.

Shigeru Miyagawa

Visualizing Japan: an online course jointly produced by Harvard University and MIT

Years ago, Professors Shigeru Miyagawa and John Dower set out to study history by looking at visual materials. Their first case study was a well-known event in Japanese history: the arrival of U.S. Naval Commodore Matthew Perry in Japan in 1853 with the purpose of “opening up” Japan to the world. The two professors collected images from museums in the U.S. and Japan and found surprising, never-before-studied results.

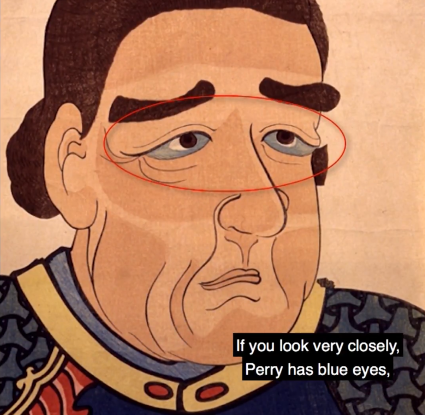

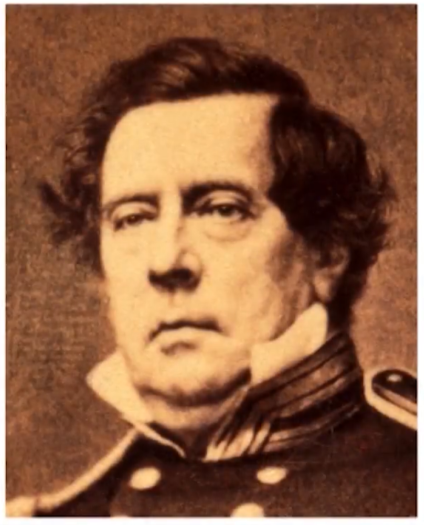

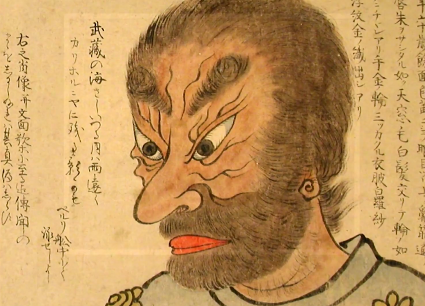

Consider for example the three images below. On the right is a photograph of Commodore Perry taken by a U.S. photographer, which exudes power and authority. On the left is a woodblock print from the Nagasaki Museum, a seemingly comical image. Upon closer examination, you can see that the image also actually reveals power and authority, but through a mistake by the artist! Commodore Perry’s eyes are blue, but they are blue in the wrong location, which shows that the artist had heard that westerners had blue eyes, but never actually saw Perry. Turns out, the Commodore made himself inaccessible during his Japan visit to project power and authority. As a result, the Japanese image is actually quite respectful, though the same is not true for a later image (below) of Perry, which was created after the United States’ real motivations for visiting Japan were revealed. So much about the two countries’ perceptions of the event through time can be gleanedgl from just three images!

Consider also the contrast between the two images of U.S. ships going to Japan below. The image on the left, from the Chicago Historical Society, is a sombre depiction of “manifest destiny,” with U.S. ships going “from enlightenment into darkness.” On the right, the woodblock print from Japan depicts the same ship, but makes it look more demonic than enlightened—you can see that the artist understood Perry’s dark mission. Notice also how the American ship is traveling from left to right, while the Japanese is going from right to left. This has to do with the differences in the two countries’ writing systems, with the traditional Japanese system going from right to left, and the English system going the other way.

Professors Miyagawa and Dower have now collected visual materials for 50 historical units. They have made agreements with over 200 museums and private collections from around the world to provide images for the project, many of which were previously inaccessible to the public. Thanks to the Visualising Japan project, you can now view and use thousands of relevant historical images, available through Creative Commons online here.

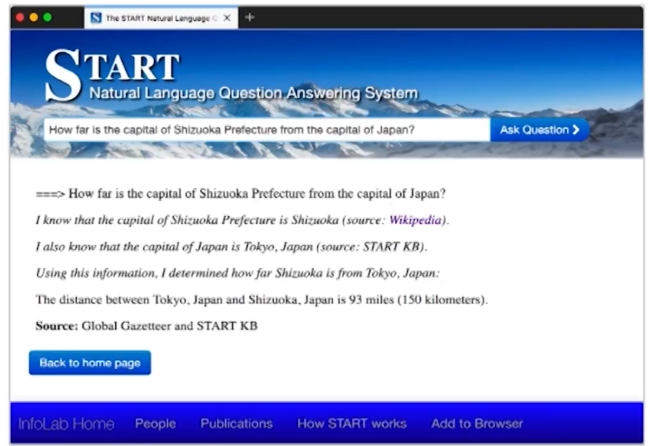

In 2014, Professor Miyagawa set out to create an online edX course on Visualizing Japan, along with John Dower, Gennifer Weisenfeld of Duke, and Andy Gordon of Harvard—four eminent scholars from three major institutions teaching together, all thanks to the online platform. Prof. Miyagawa also asked the prominent University of Tokyo sociologist Professor Yoshimi Shunya to do a sequel course, which resulted in two additional online courses on post-war Tokyo. Next steps for the edX resource now include setting up an AI system to allow online learners to ask questions about the course content and Japan in general. The prototype is now being implemented with the help of Boris Katz from CSAIL.

Most surprising, however, has been the impact of the Visualizing Japan online platform on residential MIT education. After teaching the course at MIT in its traditional format for many years, Professor Miyagawa installed the online content as primary educational material for the class in 2014, and the move has completely changed the way he teaches the class. In the traditional format, the instructor spoke for 80% of the class, and students for 20% (as timed by a student). Now the split is 50/50! And not just that, but the course attendance has been nearly a 100%, a testament to how much students appreciate the new flipped format.

Ian Waitz

Creating a Movement: an update on efforts to improve the first-year experience at MIT

The most recent major structural change to the first-year MIT undergraduate experience happened in 1964—the year Dean Ian Waitz was born! Since then, the world has changed, but not for MIT freshmen. Now the Institute is finally taking steps to address student and faculty concerns in our changed society.

In a broad effort, Dean Waitz and colleagues have interviewed multiple stakeholders on the first-year experience. Students, alumni, faculty, and industry leaders all contributed unique perspectives, with some emergent themes around student needs: more flexibility, ability for intellectual exploration (especially for choosing a major), improved advising, and desire to feel inspired by a topic or love of learning in general. These four ideals are currently poorly represented in the first year—most students take GIRs (General Institute Requirements), which often do not align with students’ interests and hinder exploration of their field of interest.

Besides talking to stakeholders, Dean Waitz and his team are also taking steps to implement the ideas they hear. Although there is a variety of needs and no consensus on objectives, the Institute is committed to addressing the issues in some form. And now the project has been formalized into a semester-long course, 2.S991 Designing the First Year at MIT, open to members of the MIT community.

2.S991 is an educational journey that starts with students learning design and different approaches to education. Students then apply what they learned in the hopes of actual institutional change. It’s the kind of work that cannot happen in a simple faculty committee. And the MIT community has thoroughly embraced the challenge. The instructors had hoped for 20 students in the course, booked a classroom for 55, and are now anticipating close to a 100 participants! The high enrollment shows the students’ passion for leaving MIT a better place and their willingness to take on complex, interdisciplinary design challenges.

The course has already begun, but Dean Waitz still invites interested members of the community to join! If you are a participant, mentor, subject matter expert, or just someone who has thoughts to share, you can engage with the class by going to this link: ovc.mit.edu/fye_course/. The more people are involved, the better outcomes we can expect for future MIT freshmen.

Barton Zwiebach

On-campus Experiments with Online Learning Using the Quantum Mechanics Sequence

MIT is one of the few schools that offers three quantum mechanics courses at the undergraduate level. The first in the series is 8.04 Quantum Mechanics I, offered twice every year. 8.05 and 8.06, Quantum Mechanics II and III, respectively, are only offered once per year, which has caused enough student scheduling issues that the department decided to try something new to address the concern.

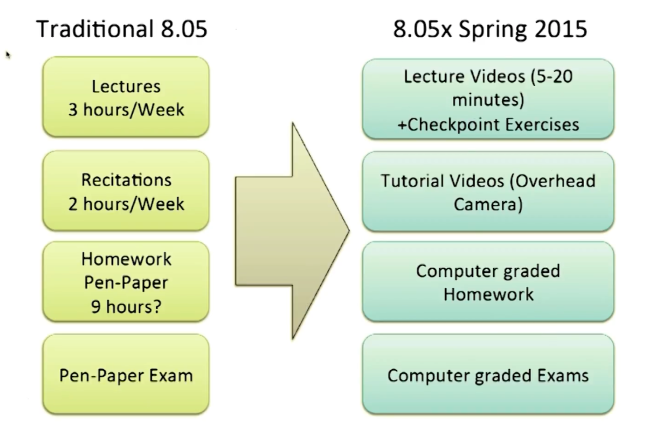

Now, 8.05 will be offered twice a year: once in its original but enhanced form with new online tools, and the other time in the form of 8.051—a fully online blended learning course, which has just approved by the Committee on Curriculum to become a permanent staple in the department. 8.051 will be run simultaneously worldwide through edX, so instructors will get insight into the class performance of many different populations.

So how is 8.051 (previously 8.S05) different from its traditional counterpart? The blended version keeps recitations and paper exams, but adopts online tools for lecture and homework. Lecture videos are enhanced with checkpoint exercises, and problem sets are computer-graded to provide instant feedback.

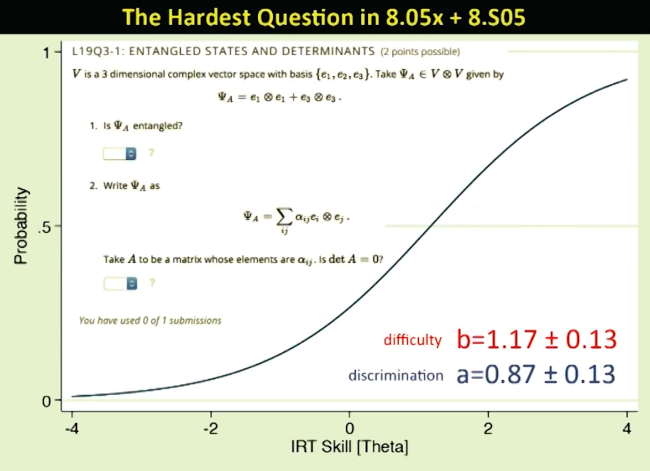

Automatic grading is not only helpful to students, but is a great tool for instructors trying to improve the course—they get data on the performance of students in the online course from across the world! From that, the instructors can judge the difficulty and effectiveness of each exercise, as well as see how the probability of getting the answer right increases along with the ability of each student.

Online computer-graded exercises aren’t the only benefit of the blended format of 8.051. Students appreciate the flexibility in their lecture viewing schedule—many report watching videos in bed, often multiple times to better understand the concepts. They also appreciate the ability to prepare for recitation better with the checkpoint exercises, which also come with immediate feedback. Students have also praised the flexibility of the online tools—the software will now recognize the correct answer to the problem even when written in multiple different ways.

Students also report drawbacks to the online tools. For example, the automatic grader does not provide much feedback on incorrect solutions, nor does it provide partial credit. These tools are still in development.

The instructors of the Quantum Mechanics sequence are still working on optimizing the 8.051 Quantum Mechanics II experience, as well as working on making 8.041, the online blended version of 8.04 Quantum Mechanics I, a permanent part of the Course 8 – Physics curriculum. Work on the online version of 8.06 Quantum Mechanics III will be completed in spring 2019, at which point the whole quantum mechanics series project will be reevaluated for an even better undergraduate experience. Prof Zwiebach’s work was helped by Saif Rayyan and Jolyon Bloomfield.

Jeff Grossman

Goodie Bags in 3.091: Hands-on chemistry learning through take-home mini-experiments

What’s more important in introductory chemistry: lecture or lab? The answer is, of course, both. Unfortunately, regular labs are infeasible in a large class like 3.091 Introduction to Solid State Chemistry, which satisfies the Chemistry GIR (General Institute Requirement). So how can the lecture be complemented without trips to the lab? How can students be encouraged to keep exploring and thinking about the material?

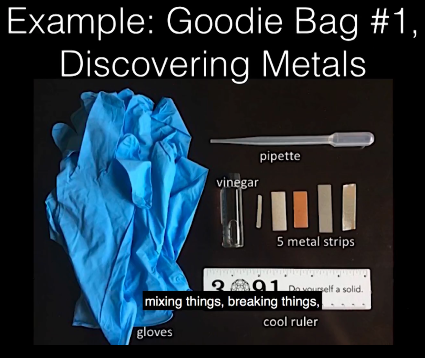

The answer for Prof. Grossman was in “goodie bags”—hands-on mini-experiments for students to try at home, to “touch and feel” the chemistry learned in lecture. The unexpected inspiration for this learning aid came after Prof. Grossman attended a birthday party with his 6-year old daughter, where she received her own cheap candy and toy bag. What if the goodie bags contained basic chemistry materials instead?

The goodie bags are now a popular staple of 3.091, which Prof. Grossman took over in 2015. One of the bags, for example, is “discovering metals,” which allows people to experience differentiating elements in the manner of early chemists—by smashing, burning, breaking, and mixing materials. The bag includes some simple supplies: vinegar, a ruler, and a set of metal strips, which the students are asked to distinguish. Sometimes, the students even continue the process of exploration beyond the given set of strips—Prof. Grossman has seen pictures of students dropping vinegar on various metal items in the Infinite Corridor.

Another popular goodie bag explores electronic transitions using the Bohr model. It lets the students go beyond the theoretical model and actually see the transitions: when they happen and when they don’t. The bag includes a spectrometer and various LEDs. It also includes a problem sheet, which is part of the week’s homework.

Thomas Kochan

Blending online and campus courses: 15.662x Shaping the Future of Work & 15.662 Managing Sustainable Businesses for People & Profits

Thomas Kochan’s favorite thing at MIT is the blended online course 15.662x Shaping the Future of Work. This course is a way for MIT MBA students to learn about the next generation of the workforce from the workforce itself. Here’s how it works: MBA students take the course on campus, concurrently with students online on edX, who are workers with a median age of 32 (and the maximum age of 83), so the MBAs get the opportunity to engage with and learn from the workforce directly.

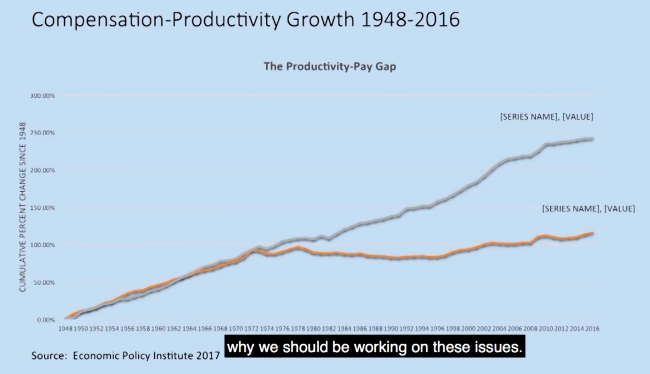

Professor Kochan is highly invested in the project, even though he receives no credit for it at the MIT Sloan School. So why does 15.662x exist? The course is important today especially because of current societal pressures, such as income inequality, social tensions around immigration, concerns about globalization, and worries over technological advances. The course is important because the old social contract in the workforce is not working anymore, and we need to renegotiate it for a better world. As you can see in the graph below, workers’ wages have been growing disproportionately slowly compared to the level of inflation, creating the giant wage gap we see in the United States today.

The online course is aimed at getting MBA students to think about what they can do to shape the future. At the core of the course is the idea of choice, for both business leaders and their employees. 15.662x brings the two sides together to build a new social contract for the workers (online students) and future leaders (Sloan MBAs). The contract is the major assignment the whole class leads up to—it is the combination of weeks of research, negotiation, and discussion. Some students even go past the class to continue research and pen op-eds about their experience. And those who cannot take the class can experience its condensed version at the week-long Sloan Innovation Period.

15.662x is a rich way of linking on-campus work with the outside workforce. Thee online course is a tool for engagement, and it is working. Professor Kochan’s favorite student course evaluation stated, “They don’t think the way we do!”—the key point of the course. It is now more important than ever to consider such workplace issues as insurance coverage, technological development, communication tools, and harassment and discrimination. Professor Kochan invites everyone to join the online course starting March 20 on edX: https://www.edx.org/course/shaping-the-future-of-work.