Skipping Class and Failing Bio by Joel G. '18

A practical guide to poor life choices

Fall semester began as expected, with a shot of adrenaline and confidence. This translated into a flurry of calendar-marking, schedule-planning, promise-making, and more personal resolutions than all of my New Years’ combined. Of course, this was typical: in high school, I perpetually resolved to become the model student I felt pressure to be, but my plans never materialized and my daily calendar just symbolically slouched untouched in the bottom of my locker.

But this year was going to be different. This was MIT, and I couldn’t afford the same procrastinatory luxuries I previously enjoyed. I would have to be rigorous, I told myself, and I would be forced to buckle down and get seriously serious about my education. When September rolled around, I set my alarm for an ambitious 1 whole hour before each daily class. I resolved to never skip lecture. I promised myself I’d eat a healthy, wholesome breakfast every single day. Also, I’d call my parents at least twice a week and take my garbage out when it got full.

Ha.

Hahahahaha.

That plan worked for a while. But by the second week of classes, a curious phenomenon began… phenomenizing. I started staying up later, but not because of homework. I was getting up later too, and had begun cutting short my dedicated “Breakfast at Baker” hour. Soon my 10am 7.012 (Biology) lecture fell prey, and, by the third week of classes, I just stopped attending.

That escalated quickly, so let me restate it: I stopped going to class so I could sleep in.

That’s OK, Joel, you’ll survive – you can get all the material from recitation or from the online video lectures on MITx.

Then, in early November, I apparently concluded that I had not made enough poor life choices. To accommodate my increasingly nocturnal schedule, I began sleeping through not only 10am 7.012 lecture, but also 11am 8.01 lecture and my 1pm 7.012 recitation. This was a problem because A) 8.01 lecture is mandatory, and B) 7.012 recitation was literally my only remaining means of learning the material, since I had proven myself far too undermotivated to watch the video lectures on my own.

Now, 8.01 (Physics) lecture isn’t really a lecture, since the class is taught in a TEAL format, and it’s only mandatory to the extent that attendance comprises about 5% of the final grade, assessed through recorded clicker responses to in-class concept questions.

That’s OK, Joel, your grade is high enough to take the hit. Besides, you took physics in high school.

But in Biology, I had effectively dropped off of the academic map, and my 7.012 grades started dropping accordingly. I struggled to hit 70% on homework that should have been trivial. I found myself frantically googling phrases that I heard my friends toss casually around. I scraped by with a 66% on the second test, and then a 37% (!!!) on the third (and last). When the last pset got assigned, I legitimately could not start to answer a single question.

I didn’t turn that pset in.

OK, maybe this wasn’t the greatest idea.

When the week before final exams rolled around, I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. I was so comprehensively lost it was hilarious, and yet, at a 65% grade average in the class, I was at serious risk of failing the course. 7.012 is a GIR, which means I have to pass it to graduate, and I really did not want to suffer through it again. The final exam was on a Tuesday, but, by the Friday before, I still hadn’t looked at the last two months of material.

Welp.

Many times in high school, I observed that my chronic procrastination problem was not a result of laziness, but instead was a simple function of time-dependent motivation. My mind just refused to work on a project if it knew it could finish it later without consequence. Instead, I’d just delay working until I got legitimately scared by how close the deadline was (usually a matter of hours), at which time my brain would plunge into an emergency panic overdrive mode. While in Emergency Panic Overdrive Mode, I could streak through weeks of calc homework in an evening or churn out research papers of arbitrary length before sunrise. If I had to do it, I would make it happen. Otherwise, I just browsed reddit.

Saturday afternoon – three days before the final exam that I needed to pass – I entered Emergency Panic Overdrive Mode. I purchased an egregious amount of Mountain Dew and barricaded myself in one of the super useful reading rooms on the 5th floor of the Student Center. There, I plugged in my headphones and opened the long-neglected video lectures.

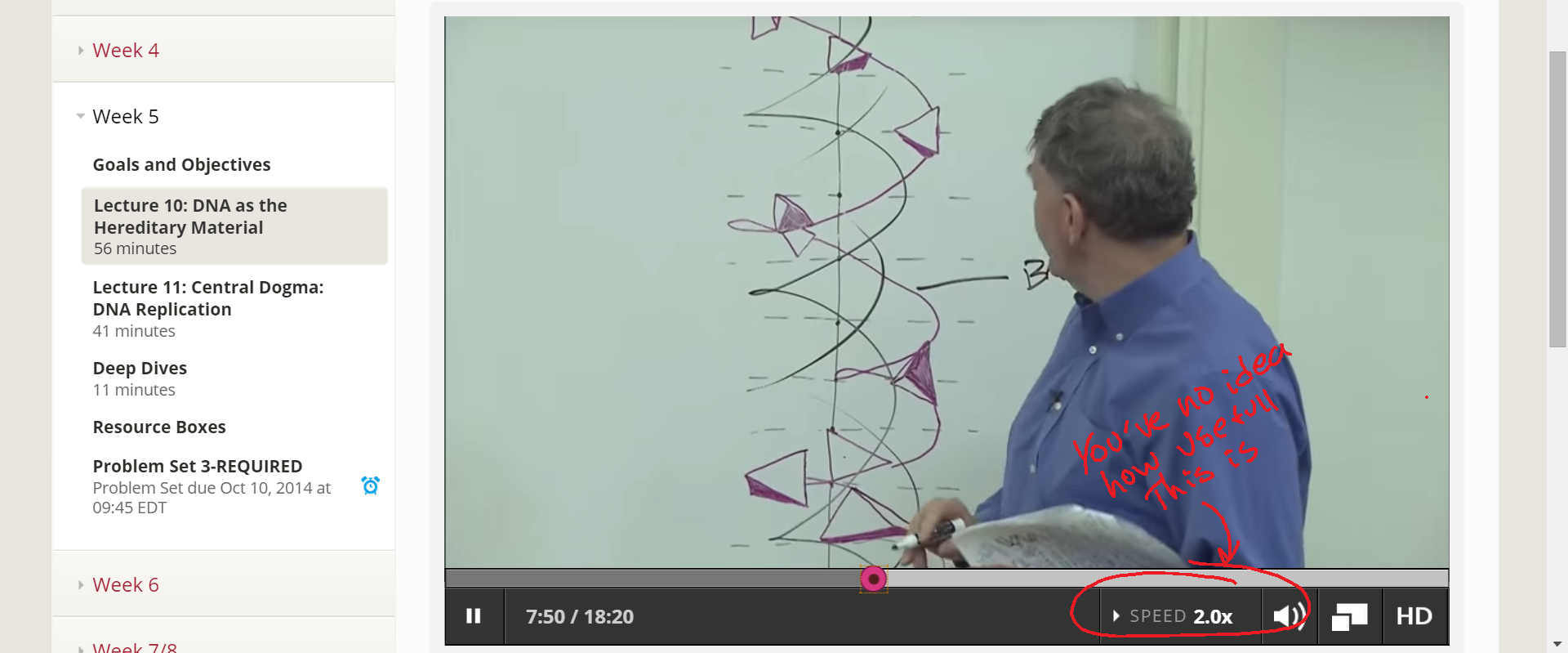

The beautiful thing about MITx is that their video player has a built-in playback speed adjuster. That means that I can listen to Professor Eric Lander’s voice zip along at twice its normal velocity. This, along with a focused concentration and heavy doses of caffeine, allowed me to cruise through 24 lectures in just 13 short hours, spread across Saturday and Sunday. It was the most information-dense weekend I’ve ever subjected myself to, and it was grueling to just sit and force myself to concentrate for hours on end. I would not recommend trying this at home.

So is an oncogene a repressor or an activator? Or is that a proto-oncogene? Or do you pronounce it ‘protOOOncogene’? Can we just go to sleep now?

Monday morning was the 8.01 final. Surprisingly, my physics grades were actually quite good, and I walked out of the 3-hour exam after just 60 minutes. I even answered all of the questions! Most of them were even correct! I promptly took a nap, then went back to studying for 7.012’s exam the next morning. This time I went through all of my psets, reviewing common question formats. If I didn’t understand something, I’d ask a friend. Or Wikipedia. I became close friends with Wikipedia.

Tuesday morning came and went. I wore a suit to the final, because if I was going to fail, I wanted to fail in style. The test was everything that I expected it to be – it was difficult, it was challenging, and it was about Biology (good). I gave every question my best shot, even if I knew I didn’t understand the problem fully.

And then I was done. It was all over.

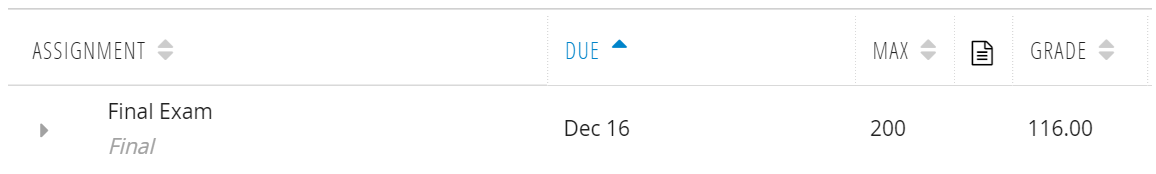

It was a strange feeling – I felt simultaneously exhilarated and hopelessly, precariously nervous. In just a few days I’d find out if I’d wasted an entire semester only to fail my first class at MIT. Final exam scores were released later that week. I pulled up the online gradebook, and, at the moment of truth…

… found out absolutely nothing, because even with my percentage, I wasn’t sure if I passed the class. Is 58% on the final passing? Is a 63% average passing? I hope so, because that’s what I have! I had to hyperventilate for several more days until class grades were finalized on my transcript. When that finally happened, at the real moment of truth…

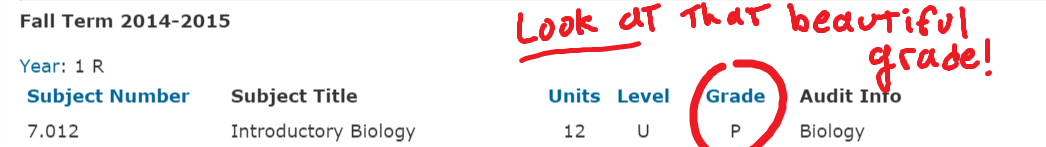

I PASSED! I actually passed! And not only did I pass, but, thanks to the wonderful gift to humanity that is Pass/No Record, nobody will ever know how close I was to failing 7.012 entirely. Well, you all know since I just blogged about it, but don’t tell my future employers, OK?

I’ve thought long and hard about what the moral of this story should be. What should I take away from this? Certainly not that I can afford to skip classes regularly, since, with the end of Pass/No Record, grades actually matter. And certainly not that I should be a Biology major, since, about 12 seconds after handing in the final exam, I flushed everything I learned that weekend out of my short-term memory.

In the end, I have no ragrets regrets. If I had used this procrastinate-and-cram tactic to pass a more essential class, like 18.02 or 8.01, I would be disappointed in myself, but since 7.012 is almost as distant from my major as it is from my memory, I’m not concerned. I’m also glad I tested my limits. To be fair, I’m even more glad that I passed, but I feel much more aware of what I can handle and how I can handle it. I wouldn’t dissuade anyone who wants to skip lecture – great! – but know what you’re getting yourself into, and don’t deceive yourself into thinking it’s easily sustainable.

And definitely don’t blog about it. Then everybody will know.