The Optimal Solution by Neerja A. '16

It doesn't exist

My first two weeks of GEL kicked off to a great start. I really like working (some would even call it playing) with my team. To help us get to know each other, our team leader and I met up over coffee. Or rather, the excuse of coffee since neither of us is a fan. One of his questions posed to me was: What do you want to work on during junior year?

Junior Year. Wow. I’m already half way done. I only have two more years to make the most of MIT. I need to decide what I want out of my MIT experience. I need to decide which classes to take and where that will lead me. That in itself has been an necessarily more stressful decision than it needed to be.

And so one of my goals this year is to work on decision making.

As the ultimate optimizer engineer, my long convoluted decision making process relies on resources – time and people – as fuel for information. I’m always working towards the most optimal solution.

But engineers, we don’t always have all the information at the same time. Or the amount of information cannot possibly be processed to the highest degree of accuracy for optimization. Often, you have to make judgement calls of whether to launch a shuttle, race a car, finance a project based on limited data in the face of high risk. One of the things the Engineering Leadership Labs (ELLs) teach us is: It’s better to make a bad decision now than a good one too late.

Last April I faced a major decision when choosing between two job offers. One allowed me to spend a summer with my family at home while learning about engineering in the oil industry. The other sent me across the world in Mumbai to get a rare opportunity in project planning on a major oil investment. Better yet I had to make my decision in a week.

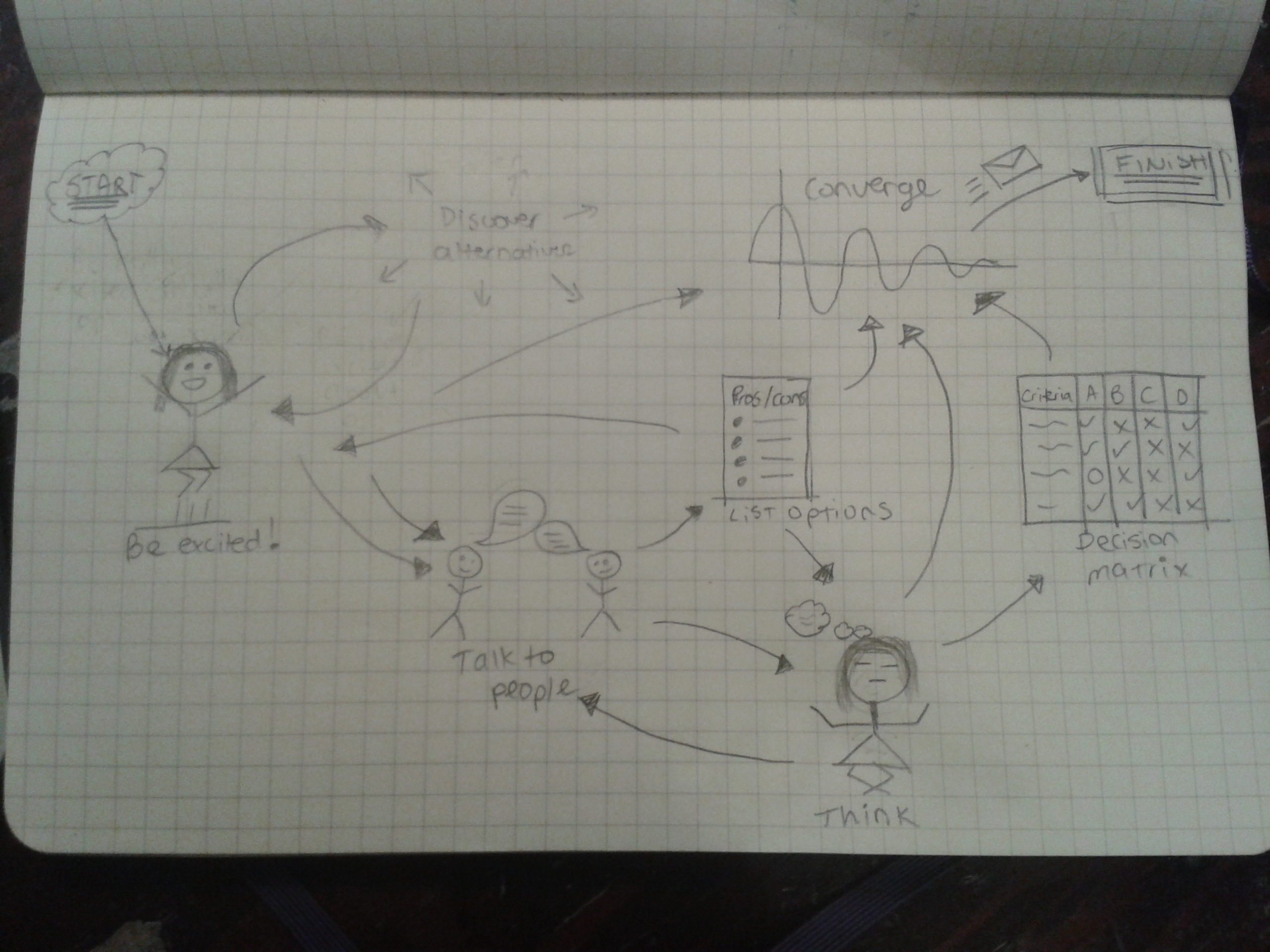

Everyone deals with decisions their own way. My process looked something like this:

As you can see, there’s no cascade of steps to follow. It’s a lot of talking and being excited and jumping around.

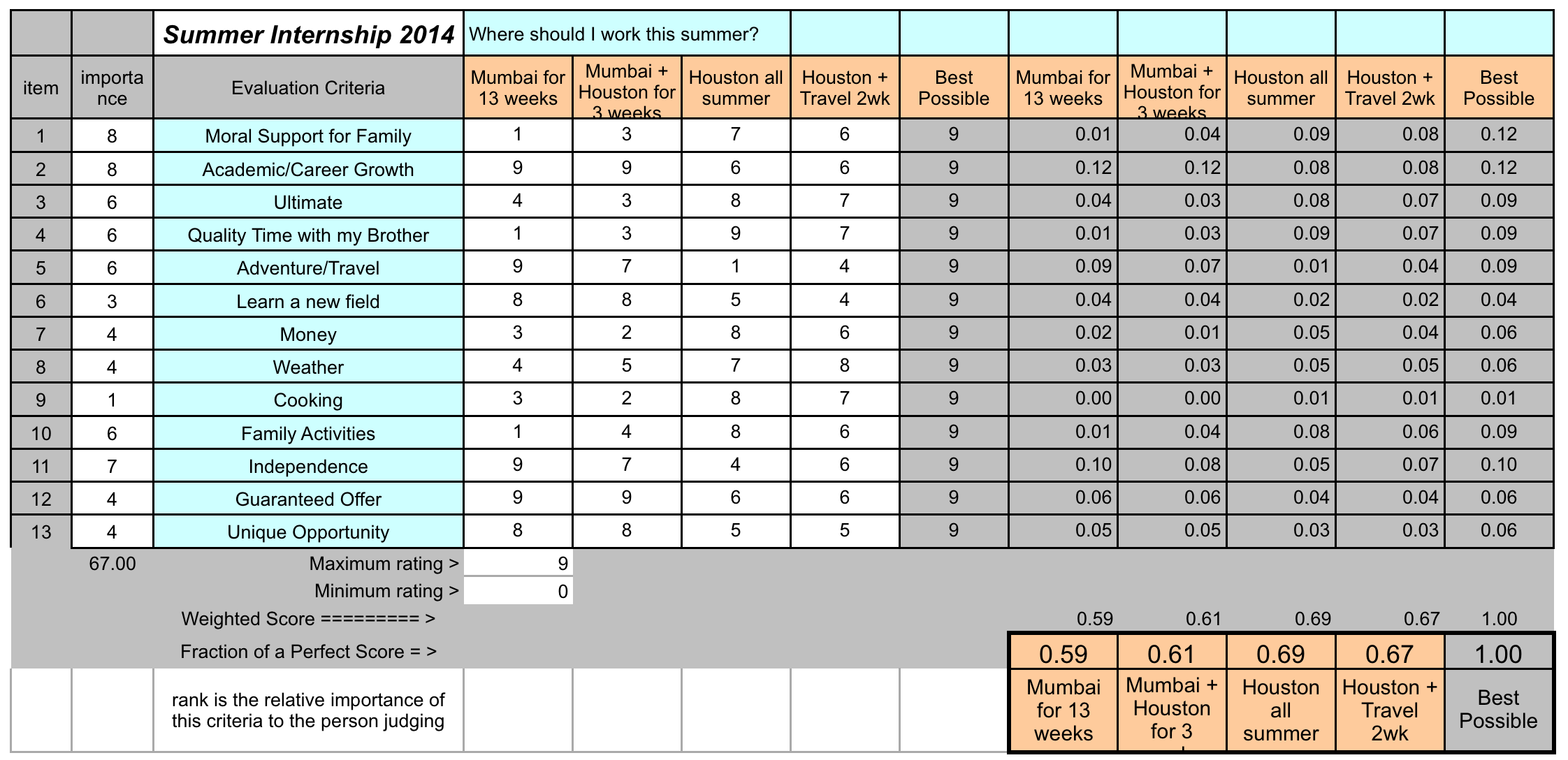

When deciding my summer internship, I even used a decision matrix in which you rate criteria and options separately to weigh your choices against your values. This functioned as a more systemic method to organize how I felt about each option rather than getting tangled in my thinking. My most important factor was family. Others were career skills and playing ultimate this past summer. The final score in the decision matrix is not what determined my decision. Rather, looking back and having that matrix warrants why I made the decision I did.

Did my process work? Did I have the most perfect summer?

Yes. No. Maybe. In the end I decided to spend my summer in Houston. But! I still got a chance to go hiking in Yosemite after finals!

That’s the view of Half Dome wayyyy in the back! We climbed that!

California was very pretty <333

And then back home in Houston, I got to play a ton of ultimate with a local club mixed team!

(That’s me! #47)

And I spent lots of time with my family.

Boston just doesn’t compare to the Tex-Mex you find back home.

Oh and also had a real job! At this very pretty campus.

It may not be Google, but we still had a full cafeteria and gym! And there were pancakes for breakfast!!! (I love breakfast.)

Parts of my summer I loved; the other parts I disliked intensely. I missed my MIT friends. I missed Boston weather. I missed the flexibility of working when I wanted to.

So did I make the wrong decision?

Looking back at the decision matrix, I had rated family time, playing ultimate, and learning about engineering in the industry as my top criteria. Turns out, I didn’t realize working full-time was such a significant time-commitment and didn’t get to spend enough time with my brother. But I found an awesome team to play ultimate with. But I didn’t know this at the time. One thing I’m slowly learning is: Don’t judge a good decision by how the consequences turn out. A good decision is based on how well you processed the data available to you at the time.

What can I do better?

This past week, I had the opportunity to speak with a GEL alum and he gave me a pretty solid piece of advice.

Why?

That’s exactly the question I should ask myself at least 5 times. The root cause analysis we learn in EID and D-Lab Design can be applied to life. Use WHY to critically analyze what motivates you. Then use that as an important factor when making decisions.

Why did I decide to direct a play this fall on top of a bazillion other responsibilities?

That’s a good question for next time.