MIT after SFFA by Stu Schmill '86

technology and the dream, deferred

Today I spoke with MIT News about the impact the Supreme Court’s decision in the SFFA case had on the composition of the Class of 2028, why it matters, and what we plan to do next. You should read that interview, as well as an accompanying message from President Sally Kornbluth.

Here, on the blogs, I want to share some personal reflections on what this means to me, both because I am ultimately responsible for the makeup of our undergraduate student body, and also because MIT has been my home for more than forty years.

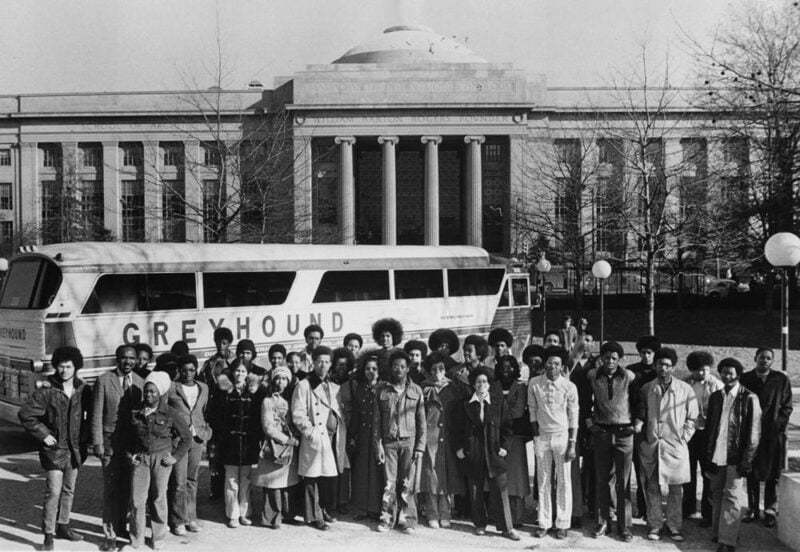

One hot summer day, many years ago now, I packed a green Army surplus duffle bag full of all my clothes and boarded a Greyhound bus to Boston. I arrived at South Station, took the Red Line to Kendall Square, and walked along Memorial Drive until I got to Killian Court. I remember standing there, seeing the Great Dome for the first time, all on my own01 My parents — who were born and raised in the tenements on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, speaking Greek and <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judaeo-Spanish">Ladino</a> at home — did not attend college, and did not accompany me to campus. In fact, the first time they set foot on the MIT campus was to see me graduate, four years later. and feeling just enormously intimidated by the place.02 I remember that when I got my admission letter in the mail, at first I was excited, but almost immediately after felt the concern that I had been admitted by mistake. And today, at our admitted student program each spring, the number one question I get from students is some version of: “How did I get in?” Many of our students feel this impostor syndrome prospectively to some degree or other, and to them I say — unequivocally — that every student we admit belongs here, period, and has demonstrated the academic and personal qualifications to thrive at MIT and beyond. It was freshman orientation in August 1982, and I — a skinny seventeen year old Jewish kid from a public high school in Queens — was about to begin my college education at the most famous institution of science and technology on the planet.

I moved into New House — a dorm known even in the eighties for its multicultural community — where I shared a forced triple03 I later learned the Class of ‘86 had over-enrolled by several dozen students, due to high yield rate that caught the Admissions office off guard. I only knew it was a forced triple decades afterward, once I started working in admissions - we all just thought it was supposed to have three people in it. with Scott from New Jersey and Victor from Lynn, two guys I met by chance in the barbecue line and with whom I became fast friends.04 </span>...despite the fact that they liked to spin records late at night while I was trying to wake up to be on the river at 6AM for crew. That said, serendipity reigned: the three of us briefly ran a DJ business together after graduation. In those days, Paul Gray was the President of MIT,05 It is hard to exaggerate the degree to which <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_E._Gray">Paul</a> — who was not a tall man — towers in MIT history, alongside his wife Priscilla, after whom our <a href="https://pkgcenter.mit.edu/">Center for Public Service</a> is named. After earning his bachelors, masters, and doctorate in electrical engineering, he served sequentially as Professor, Dean of Engineering, Associate Provost, Chancellor, President, and finally Chair of the MIT Corporation, our board of trustees. The house occupied by the President of MIT is named after them, as is the walkway across campus along which he and Priscilla would daily wander, greeting students, faculty, and staff along the way. In 1997, when he stepped down as Chair of the MIT Corporation, his successor Chuck Vest <a href="https://infinite.mit.edu/video/special-place-celebration-honor-paul-and-priscilla-gray-5171997">said in a speech</a>, “Is Paul the image of MIT, or is MIT the image of Paul? Both, I suppose. Indeed, he personifies our institution — integrity, loyalty, tenacity, and, of course, his championing of our meritocracy.” Everything we have done in MIT Admissions — before and during my tenure as Dean — has been in this tradition set out by Paul and the students of the Task Force (below) more than a half-century ago. and could often be seen trundling across campus making spirited conversation with freshmen and faculty alike. Because I was small, but loud, I was recruited to be a coxswain of the crew team.06 Crew is a sport I didn’t even know existed before I arrived, but would become the center of my world for the next twenty years. After four years as an MIT undergraduate, I became the MIT crew coach for thirteen more, and still compete annually at the Head of the Charles. I figured out pretty quickly that I was practical and liked working on projects with my hands, so I declared Course 2, where I took 2.03 with Jim Williams,07 Jim taught me <a href="https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/2-003sc-engineering-dynamics-fall-2011/">2.03: Dynamics</a>; he was an incredible instructor, lecturing without notes while making complex topics easy to grasp; his skill as a teacher made this probably one of the few courses that I understood all the way through. Later, as part of his hunger strike for more diversity among the MIT faculty, Jim once <a href="https://fnl.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/fnl35.pdf#page=9">memorably described</a> the kind of diversity to which he thought MIT should aspire: “a broad intellectual, sociological, action-oriented and multi-ethnic community.” This vision has stayed with me ever since. 2.70 with Woodie Flowers,08 “Introduction to Design and Manufacturing,” now known as 2.007, and the class that inspired <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FIRST_Robotics_Competition">FIRST Robotics</a>, which Woodie would co-found with the inventor and entrepreneur Dean Kamen in 1992. I took it with my friend and classmate <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megan_Smith">Megan Smith</a>, who would go on to run GoogleX and PlanetOut, and later became the Chief Technology Officer of the United States. Like FIRST today, 2.70 was a great example of how people with different backgrounds can come up with different ways to solve problems, as <a href="https://infinite.mit.edu/video/interview-woodie-flowers-origins-270-robotics-competition-11997">Woodie once said in an interview</a>; I remember I was the only person with my design that year (I lost in an early round of the <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cDnSFQ4YZLc">1984 competition</a>, but to the eventual winner, which softened the blow somewhat). and 2.72 with Ernesto Blanco,09 2.72 was, then as now, <a href="https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/2-72-elements-of-mechanical-design-spring-2009/">Elements of Mechanical Design</a>, which taught students how to synthesize, model and fabricate a design from scratch and subject to real-world constraints. Ernesto — who was born in Cuba and frequently consulted with the State Department on engineering education in Latin America — was a legendary instructor and inventor, most notably of <a href="https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/ernesto-blanco">many breakthrough medical and assistive devices</a>; like many other of his students, I was in awe of his mission-minded technical creativity. among others.

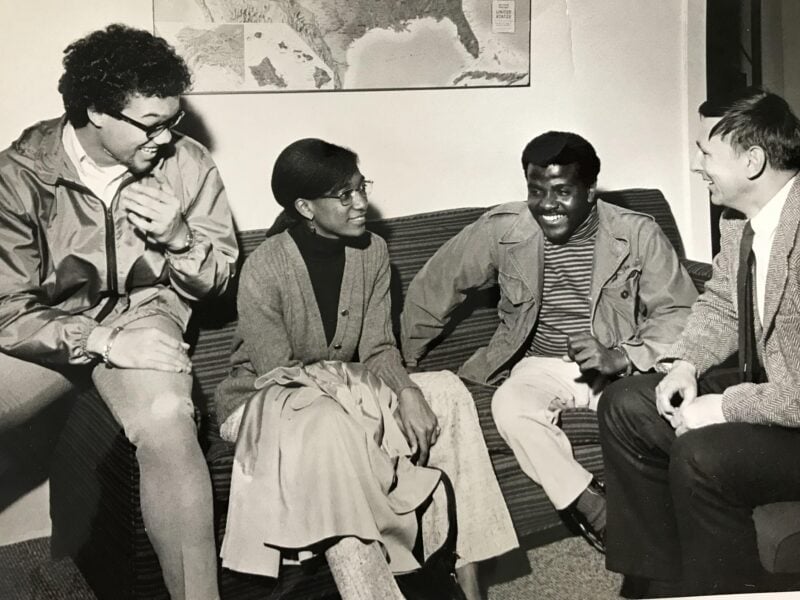

Jim, Woodie, Ernesto, and the rest of my professors taught me a lot, but like most college students, I learned even more from my friends. Like many MIT students before and since, I could not believe my good fortune to be surrounded by such incredible company. When I think back, most of what I learned at MIT and its value wasn’t even really in the classroom itself. The laws of physics are the same everywhere, and I could have picked up the basic principles of engineering from a textbook at the New York Public Library.10 As Matt Damon’s MIT-janitor character says to a rival from Harvard in <em>Good Will Hunting</em>, “You wasted ⌈your tuition⌋ on an education you coulda got for $1.50 in late fees at the public library.” But of course — and as Damon’s character later learns from his therapist, played by Robin Williams — what you can’t get from a book are the humans you meet along the way, and what they can teach <em>you</em>. It was my fellow students — who hailed from Georgia to Guyana and everywhere in between — that made being at MIT so special.

I found myself surrounded by smart, kind, creative people, who came from around the country and the world to attend MIT because we all wanted to solve hard problems in the company of brilliant peers.11 I cannot emphasize enough the centrality of learning to collaborate with others who are different from you as a core feature of our education. I briefly went to General Motors and was a design engineer for a little while after graduating from MIT. The engineering part of it was frankly simple, and I could have learned it anywhere. The challenging part of that job was working with people on big, complex projects under pressure. So that is the part of the MIT education that I think was the most valuable for me: it was all project-based work that we did, because I learned how to to generate new ideas and execute on them with other people who had different ideas and perspectives and experiences from mine. What we didn’t realize, but soon learned, is that what enabled us to actually teach and learn from each other was that we had such different ideas and experiences,12 As we argued at length in a <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/amicus-briefs-and-the-abcs-of-a-diverse-mit/">joint industry-academia amicus brief with Stanford, IBM, and Aeris Communications</a>, the educational benefits of diversity are a <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/reaffirming-our-commitment-to-diversity/#annotation-32">consistent empirical finding across a variety of disciplines</a>. More intuitively, anyone who has ever worked on any creative problem solving knows that nothing kills creativity and innovation like a monoculture, while a meritocratic pluralism of brilliant and diverse perspectives is a dynamic source of new ideas. In his classic article “<a href="https://www.bebr.ufl.edu/sites/default/files/Burt%20-%202004%20-%20Structural%20Holes%20and%20Good%20Ideas.pdf">Structural Holes and Good Ideas</a>,” the sociologist Ronald Burt studied how successful innovators in business are often people who “bridge” homogenous groups, because they “have earlier access to a broader diversity of information and have experience in translating information across groups…⌈providing⌋ a vision of options otherwise unseen.” Any MIT alum will recognize the Institute as a training ground for these kinds of bridge figures. but were united by a shared standard of academic excellence,13 As I told <em>MIT News</em>, in my time as Dean of Admissions, all admitted students, from all backgrounds, have been required to demonstrate rock-solid academic readiness for the MIT education through their performance in high school and on standardized tests. And in recent years, as MIT has grown more diverse, collective academic performance has improved, as have retention and graduation rates, which are now at all-time highs for students from all backgrounds. I emphasize this essential fact because many people have told me over the years that they think MIT ought to only care about academic excellence, not diversity. But this is a false choice, because every student we admit, from any background, is <em>already</em> located at the far-right tail of the academic distribution. a collective interest in science and technology,14 Though not <em>only</em> science and technology, and certainly not for their own sake. As Paul said in his <a href="https://news.mit.edu/2017/former-mit-president-paul-gray-dies-0918">inaugural address</a> as MIT’s President in 1980, “We continue to hear the complaint that...many of our human and social ills are the direct result of unanticipated and deleterious artifacts of technology, foisted upon the world by technicians with tunnel vision...What is clear, however, that the future development not only of this nation, but of the world, is inexorably tied to continued scientific progress and to the humane and thoughtful applications of science...What is needed is not a retreat from science and technology, but a more complete science and technology. We must strive to develop among ourselves, among our students, and in the public at large, an understanding of the fact that engineering and science are, by their very nature, humanistic enterprises.” and a sense of mission to use our interests and aptitudes to serve the nation and the world.15 As the <a href="https://facultygovernance.mit.edu/sites/default/files/reports/1949-12_Report_of_the_Committee_on_Educational_Survey.pdf">Lewis Report</a> described the purpose of the MIT education all the way back in 1949: “We believe that the mission of the Institute should be to encourage initiative, to promote the spirit of free and objective inquiry, to recognize and provide opportunities for unusual interests and aptitudes; in short, to ⌈develop⌋ individuals who will contribute creatively to our society, in this day when strong forces oppose all deviations from set patterns.” The modern <a href="https://www.mit.edu/about/mission-statement/">MIT mission</a> directs us to “educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century.”

I wasn’t all on my own after all. I had all of them, from every walk of life, with me every step of the way down the Infinite Corridor.

My classmates and I benefited from the fact that, even back in 1982, MIT already had a long history16 The best guide to this history is Dr. Clarence Williams’ indispensable <a href="https://dusp.mit.edu/people/clarence-g-williams"><em>Technology and the Dream: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT, 1941–1999.</em></a> Clarence and I first became friends in the 1990s, when I was the head crew coach, and he was Special Assistant to the President of MIT for Minority Affairs. Back then, I volunteered coaching a rowing team of teenagers from the Mandela Apartments in Roxbury. In addition to borrowing some of our boats, I opened the MIT Boathouse to them so they could train alongside MIT undergrads, and they eventually became <a href="https://news.mit.edu/1997/crew-1119">the first team of all Black and Hispanic students to compete in the Head of the Charles</a>, for which they were celebrated by ABC’s <a href="https://youtu.be/c_zRkCAyVps"><em>World News Tonight</em></a>. Clarence, who was <a href="https://dusp.mit.edu/news/clarence-williams-honored-mlk-celebration-gala">honored earlier this year</a> with a lifetime achievement award at the 50th Anniversary MIT MLK Celebration, was a central advocate of this initiative and helped manage the relationships and build support; we saw it as a way that MIT could share its intellectual, social, and material resources with the community, in keeping with our mission and our land-grant charter. Later, when I ran the Educational Council, I shared an office in N52 — the old MIT Museum building — with Clarence, while he was finishing work on this book. “MIT served as a pioneer in the late 1960s and early 1970s, developing admissions criteria so that black students would get an opportunity to attend this institution,” he wrote in its introduction. “Among schools of engineering and science, MIT’s criteria became a model for other institutions to increase the numbers of young minority scientists and engineers.” of advancing equal opportunity and racial integration in STEM education. Seventy years ago, in May 1954, the Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education; a few months later, MIT hosted what is believed to be the first national conference on the topic of anti-discrimination in higher education. During the early days of the Civil Rights Era, the Committee on Undergraduate Admissions and Financial Aid (CUAFA) directed more recruitment at predominantly minority high schools, and the student-run MIT Science Day Camp17 Described by the 1969 MIT President’s Report as “a remarkable demonstration of student initiative at its most creative and sophisticated level,” as so many of the student initiatives in this area have been in our history. evolved into the federally-funded national program Upward Bound.

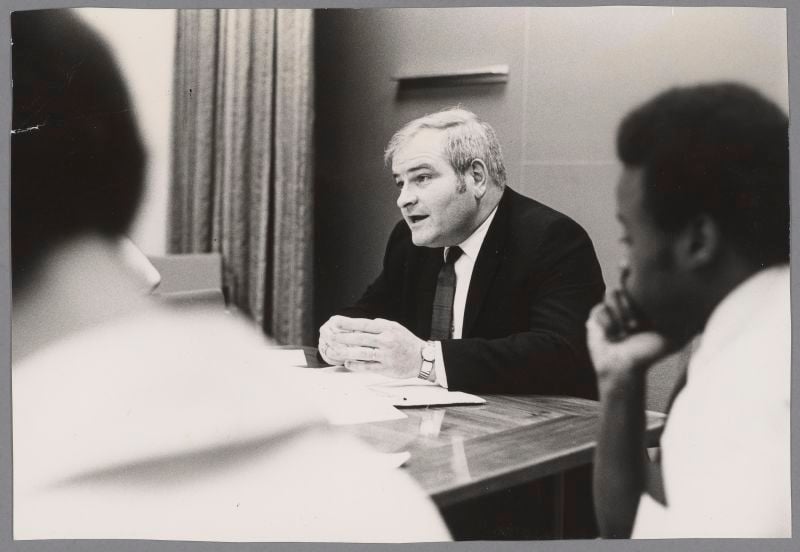

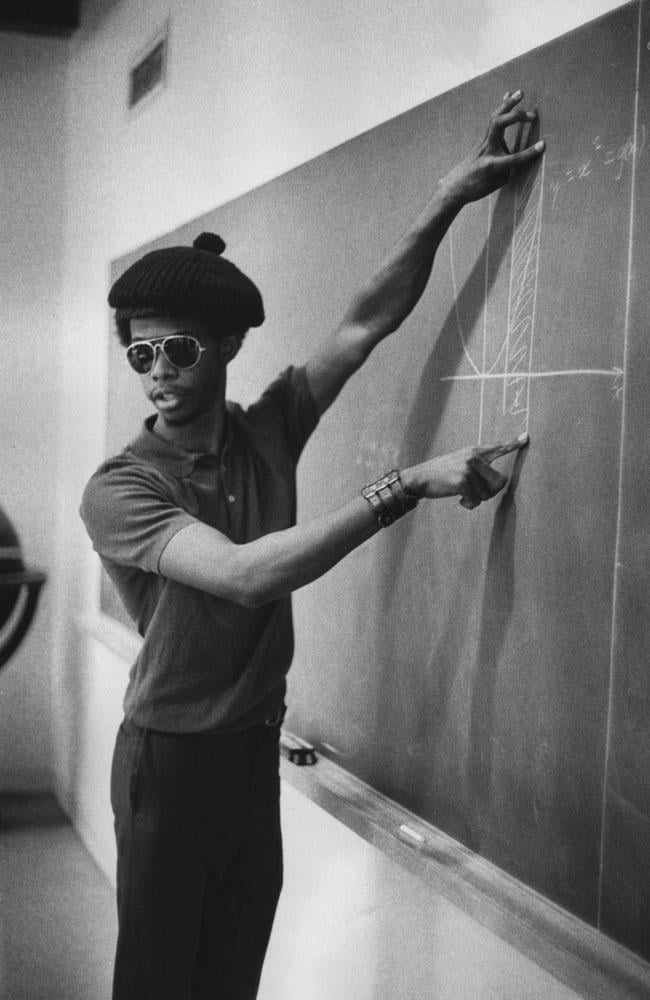

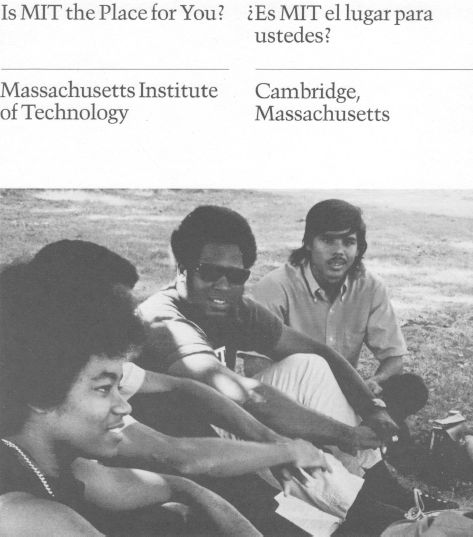

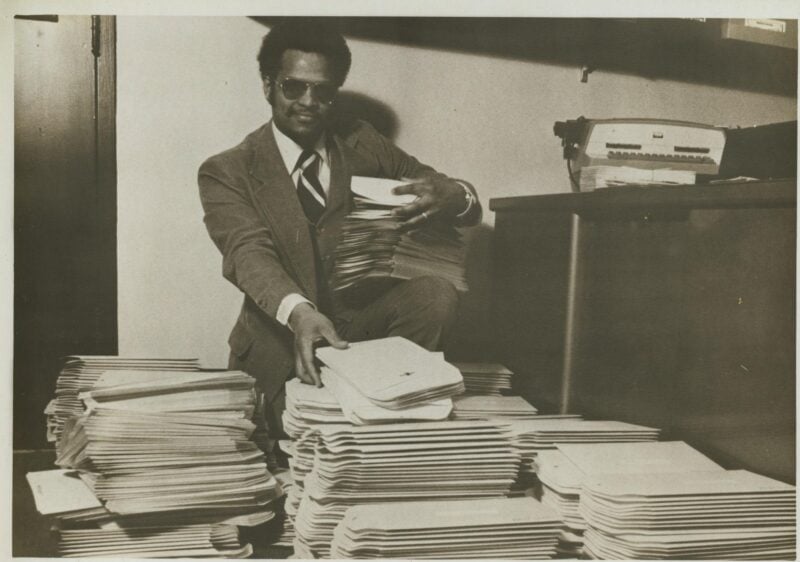

Then, in 1968, MIT launched the Task Force on Educational Opportunity, chaired by then-Professor Paul Gray and including faculty, staff, and student leaders.18 Among them a young <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shirley_Ann_Jackson">Shirley Ann Jackson</a>, who would go on to become first African-American woman to earn a doctoral degree from MIT; she later ran the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and served as the 18th President of RPI. The MIT Black Student Union she helped found was crucially involved with recommending and starting the Task Force, and led many of its key initiatives. The Task Force had a clear sense of purpose19 When asked, at a faculty meeting in 1969, why MIT was embarking on these efforts to expand opportunity, Paul said: “⌈S⌋ome of those who have in recent months commented on this program have expressed concern that the Institute has embarked, for reasons that are seen to be essentially political, on a course that will lead it away from its responsibility for the education of an elite, and will compromise its capability and its contributions in this respect. This view seems to me to overlook several important aspects of both the Institute’s traditional role, and its responsibility to the society in which it functions. Over most of its history, MIT has provided, in educational terms, the skills, knowledge, and qualities of mind that have been required to work out solutions to the problems posed by our developing society and to enable individuals to become more effective, more mobile, in that society...it seems to me that we must not fail to make those opportunities accessible on a broad scale by getting hung up on a narrow, self-serving, conception of education for an elite.” and moved rapidly to greatly expand MIT’s recruitment20 Specifically, the Task Force directed the admissions office to begin a nationwide talent-search for students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds who might do well at MIT. John Mims — the first African-American admissions officer at MIT — developed an at-the-time innovative plan to individually recruit students who had performed well on the PSAT or SAT; his initiative immediately octupled the number of admitted students from historically under-represented backgrounds. In 1996, Paul Gray <a href="https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/chapter-pdf/2410074/9780262286305_c001400.pdf">told</a> Clarence Williams: “We did then what we really still do to increase the flow of applicants, that is, we send material by mail to all those high-school students who have taken the SAT’s who at that time indicated that they were African-American—now other minorities are included—and who have scores in the range that at MIT might make sense. A little brochure went out that first year that was produced by the task force...and resulted in sort of a ten-fold increase in the number of minority applicants. That’s been the core of the effort ever since.” <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sylvester_James_Gates">Dr. Sylvester James Gates</a> — a member of the first class of students recruited via this initiative — <a href="https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/5038/chapter/2977126/Sylvester-J-Gates-Jr">told Williams</a>: “It was almost like an athlete being recruited to go to college to play ball,” except for a STEM education. and financial aid,21 Among them, an early initiative to guarantee sufficient grant-aid scholarships to Black undergraduates in the 1970s so that they could attend MIT without having to take out loans, which was especially salient given the contemporary issues with redlining. Today, all admitted students from all backgrounds <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/afford/cost-aid-basics/access-affordability/">receive scholarships that meet 100% of financial need</a> without any expectation of loans. incubate the student-led programs that became MITES and Interphase, and undertake other bold initiatives,22 I should note that in addition to of the specific efforts of the Task Force, MIT faculty also launched their own initiatives, creating new areas of teaching and research in in urban affairs, offering pro bono legal services to Cambridge minorities, and <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leon_Trilling">cofounding</a> the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/METCO#History">METCO</a>) the largest and second-longest continuously running voluntary school desegregation program in the United States. including student-run tutoring programs for Cambridge youth that exist to this day. In a report reflecting on the early years of these initiatives, Paul described the vision and values that guided these initiatives in his plainspoken manner:

We undertake these actions and adopt these policies not because we are required to, but because it is right and proper that we do so, [for] we are persuaded that the Institute becomes a stronger, more effective place as it draws on the full range of human talent and experience.

Decades later, long after his presidency and subsequent chairmanship of the MIT Corporation, Paul led the search committee that hired me as the Dean of Admissions in 2008; he also served on CUAFA. In my first few years in this role, he and I got lunch several times a semester, and I have always been grateful for his mentorship, guided as it was by both his mind and his heart. Paul never stopped being an MIT professor, first and foremost; he helped teach me everything I learned about the important work with which I had been entrusted.

What sticks with me most from those invaluable conversations was Paul’s personal conviction that his initiatives to diversify MIT23 In addition to the Task Force, his service to CUAFA, and his many years of leadership support, Paul, in the best <em>mens et manus</em> tradition, did hands-on work too. I remember him telling me stories about how, when chairing the Task Force, he would take trips to drive around in an old Cadillac with <a href="https://alum.mit.edu/aboutleadershipleadership-nominationsannual-awards/2024-award-winners#:~:text=67%20Award%20Winners-,George%20B.%20Morgan%20%E2%80%9920%20Award,-The%20George%20B">legendary Educational Counselor George B. Morgan</a> visiting high schools in Texas. So Paul — just like an admissions officer today — could see on the ground the extent of inequality of opportunity, state to state, district to district, school to school, and sometimes even within schools. That was part of what informed his deep knowledge and driving passion for this work. constituted the most important work he had done in all of his time in our leadership. Paul knew, as well as anyone ever has, that the key lesson an MIT education teaches is the skillful self-confidence that no problem is too hard to tackle, and he thought it was crucial that this lesson be made more broadly available.24 The <a href="https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/59050">1969 President’s Report</a> includes a section — likely authored by Paul, and certainly summarizing his statements at faculty meetings about the Task Force — explaining that there “are several compelling reasons for undertaking intensive efforts to increase the number of Black Americans who study at the Institute. First, the science-based education for leadership, which has long been our strength, is as relevant and as essential in the Black community as it has proved to be for others in this society. Second, our commitment to areas of science and technology which bear on critical social problems, such as the broad area of urban affairs, requires that Black Americans, who have a major stake in these concerns, participate fully in the development of solutions...The Institute has much to offer in terms of the kind of education that elevates, empowers, and liberates people, and it seems to me that we must not fail to make those opportunities accessible on a broad scale.” He impressed upon me that carrying on this legacy of meritocratic pluralism — the synthesis of diversity and excellence — was an essential responsibility for the Dean of Admissions at a place like MIT.

This responsibility looms large in my mind, and weighs heavily in my heart, as I contemplate the change to MIT brought about by the Supreme Court’s decision in the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA) case last year. In an interview with MIT News today, I discussed the impact of the Court’s decision, why it matters, and what we plan to do next. I encourage you to read the full interview, but here are the five key things you really need to know:

- After the SFFA decision, we expanded our recruitment25 We have long conducted focused recruiting on under-represented and under-served students, and expanded our recruitment budget for these efforts this year, including our <a href="https://news.mit.edu/2023/3-questions-stuart-schmill-mit-admissions-stars-college-network-0404">ongoing partnership with the STARS Network</a>. We also have long offered visit weekends hosted on the MIT campus for those who would benefit from an introduction to STEM, sent direct mail about MIT to students from under-represented and under-served backgrounds with unusually strong testing, and so on, as I have described above. Of course, we can (and must) always improve recruiting, but as I describe below, the challenges are more fundamental than that. and financial aid initiatives26 As a first-generation college student who relied on scholarships to attend MIT myself, I am proud that <a href="https://sfs.mit.edu/undergraduate-students/the-cost-of-attendance/making-mit-affordable/">we operate one of the most generous financial aid programs in the country</a>, with around $160M in grants distributed to our ~4,500 undergraduates to help them meet 100% of their financial need. Today, the <b>median</b> need-based MIT Scholarship is $66,663, and 39% of our undergraduates receive grants at least equal to the cost of tuition. In addition to the new policy described in this bullet point for families making less than $75K a year, and our continued policy of being tuition-free for families making less than $140K a year, we also expanded our spring yield program budget to cover all transportation costs for any admitted students receiving any amount of financial aid to attend Campus Preview Weekend, Ebony Affair, and/or Sin LíMITe, to ensure any admitted student could afford to come experience the MIT community. to further improve access to the Institute for students from all backgrounds, led by a new policy whereby students from families earning less than $75,000 a year pay nothing to attend27 This is the kind of clear commitment that has been <a href="https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20200451">empirically demonstrated</a> to lower barriers for low-income applicants. It also allowed us to quintuple the number of students we match through <a href="https://www.questbridge.org/">QuestBridge</a>, a program for high-achieving, low-income students that requires students receive full scholarships covering the total cost of attendance in order to match them.

- Despite these initiatives, and as we expected,28 <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/reaffirming-our-commitment-to-diversity">As I wrote last year</a>, we had closely reviewed what happened in states that banned race-conscious admissions before <em>SFFA</em>, including Professor Bleemer’s <a href="https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004727272300021X">landmark study of the University of California system after Proposition 209;</a> <a href="https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/kidder_paper.pdf">Kidder and Gándara’s expansive report</a> on what the University of California system had tried to reverse the decline in the decades since; the University of Michigan’s <a href="https://record.umich.edu/articles/u-m-files-amicus-brief-in-support-of-harvard-and-unc/">amicus brief</a> in the <em>SFFA</em> case; and Ellison & Pathak’s <a href="https://blueprintlabs.mit.edu/research/the-efficiency-of-race-neutral-alternatives-to-race-based-affirmative-action-evidence-from-chicagos-exam-schools/">study of Chicago’s exam schools</a>. In short, all of these studies showed a significant decline in students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic groups after prior state or secondary school bans on race-conscious admissions. The strongest effects were seen at the most selective, and most STEM oriented, programs; MIT is at the molten core of this intersection. We believe our research-informed initiatives — in particular our major expansion of financial aid — likely attenuated, but did not forestall, the decline in students from under-represented and under-served backgrounds, which is what we would have predicted based on these studies. there was still a decline in the proportion29 <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/apply/process/composite-profile/">In this composite profile</a>, we have averaged the demographic composition of the first-year classes of 2024-2027; i.e., the MIT student body as an undergraduate attending MIT last year would have experienced the composition of their own class on average. Over that time period, around 25% of recent MIT undergraduates have identified as Black, Hispanic, and/or Native American and Pacific Islander; this year, it is closer to 16%, about a 40% decline. By comparison, according to <a href="https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/2024/cge_508c.pdf">recent data</a> from the National Coalition on Educational Statistics (NCES), 45% of public elementary and secondary school students are classified as members of these groups. It is important to note that there is year-to-year variance, as we have never had a quota for the number of students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds admitted to MIT; this was illegal long before <em>SFFA</em>, and also against MIT policy set in 1968 by the Task Force. However, the decline this year is far outside the bounds of normal variance, and is more consistent with the proportion of students from these backgrounds typically seen at MIT in the late 1980s and early 1990s. of enrolling first-years from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds30 As I <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/reaffirming-our-commitment-to-diversity/#annotation-10">explained last year</a>, for the purposes of interpreting the descriptive statistics reported on the class profile, we adopt the convention of using “historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds” to count Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students, who are historically under-represented in STEM education. This is a crude standard, and one that has been (rightly) criticized for subsuming other groups — <a href="http://asianamerican.mit.edu/recs/">particularly Asian-American students</a> — into monoliths, as well as for sidestepping the sovereign status of Indigenous peoples; we acknowledge the limitations of these ways we currently <a href="http://(https://data-feminism.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/h1w0nbqp/release/3).">count people</a>. We are also aware of <a href="https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2024/03/28/omb-publishes-revisions-to-statistical-policy-directive-no-15-standards-for-maintaining-collecting-and-presenting-federal-data-on-race-and-ethnicity/">the new OMB standards for collecting and presenting racial and ethnic data</a>, as well as the <a href="https://aapidata.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Report%25E2%2580%2594Strengthening-the-Federal-Governments-Data-Disaggregation-Pillar.pdf">recommendations</a> from the advocacy group AAPI Data on strengthening data disaggregation. Because of limitations in how past data was collected and stored, it is not possible for us to implement these new recommendations retroactively on this long-term data, and our data use is consistent with long-term guidance from other federal agencies that collect statistics such as the NSF.

- This is because the SFFA decision effectively bans our ability to consider race and ethnicity31 When the Court prohibited the consideration of race <em>qua</em> race, the majority opinion noted that “nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” However, it continues, “universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.” to assemble a broadly diverse class, and students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds are under-represented due to persistent and profound racial inequality in American K-12 education32 As Kidder & Gándara put it in their <a href="https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/kidder_paper.pdf">study</a> of the California system, “While two thirds of all Latino and African American students are found in the lowest performing half of the state’s schools, a much smaller percentage of White and Asian American students attend these schools...The more shocking story, however, is told in the percentage of each group found in the top-most decile—the very highest performing schools in the state. These are the schools that prepare the bulk of incoming UC students. Here is where one third of all Asian American students are found and one in five of all White students. Yet barely 3% and 4% of Latinos and African Americans are in these schools.” Meanwhile, <a href="https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Inequities-in-Advanced-Coursework-Whats-Driving-Them-and-What-Leaders-Can-Do-January-2019.pdf">according to the Education Trust</a>, “Black and Latino students across the country experience inequitable access to advanced coursework opportunities. They are locked out of these opportunities early when they are denied access to gifted and talented programs in elementary school, and later in middle and high school, when they are not enrolled in eighth grade algebra and not given the chance to participate in Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), and dual enrollment programs. As a result, these students are missing out on critical opportunities that can set them up for success in college and careers.” Similarly, <a href="https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/Understanding_Racial_Ethnic_Performance_Gaps_in_AP_Exam_Scores.pdf">according to the College Board</a>, “we find that racial/ethnic gaps in AP Exam scores in the ten most popular AP subjects are nearly fully explained by differences in prior academic experiences, with only minimal differences attributable to other student and school background data. Students who enter the AP Program with similar academic preparation in prior grades, earn similar AP Exam scores regardless of their racial/ethnic subgroup, gender, parental education level, eligibility for an AP exam fee reduction, or school context.” In other words, these racial gaps are primarily due to the cumulative effects of unequal educational opportunity. These findings are also consistent with new research from the <a href="https://edopportunity.org/">Educational Opportunity Project</a> at Stanford, which shows that important measures of racial and economic segregation between schools have <a href="https://ed.stanford.edu/news/70-years-after-brown-v-board-education-new-research-shows-rise-school-segregation">grown steadily over the past three decades</a>, leading to <a href="https://edopportunity.org/discoveries/segregation-leads-to-inequality/">increasing achievement gaps</a> produced by the <a href="https://edopportunity.org/discoveries/white-black-differences-scores/">cumulative effect of differences in educational opportunity</a>. that is especially pronounced in the areas of math and science33 NCES data <a href="https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-educational-opportunities-report.pdf">shows</a> nearly two-thirds of American high schools where three-quarters of students enrolled are Black and/or Hispanic do not offer any form of calculus, more than half do not offer any form of computer science, and nearly half do not offer any form of physics. And even within schools where such preparation for the postsecondary study of STEM is notionally available, <a href="https://nces.ed.gov/programs/equity/indicator_f11.asp&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1721389082578614&usg=AOvVaw042FF-u59aJiTcKUSb9iC_">participation remains strongly associated with race</a>, an effect compounded by socioeconomic inequality. <a href="https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Inequities-in-Advanced-Coursework-Whats-Driving-Them-and-What-Leaders-Can-Do-January-2019.pdf">According to the Education Trust</a>, “Nationally, inequities are largely due to ⌈1⌋ schools that serve mostly Black and Latino students not enrolling as many students in advanced classes as schools that serve fewer Black and Latino students, and ⌈2⌋ schools — especially racially diverse schools — <a href="https://www.smith.edu/sites/default/files/media/Francis_Counselors_BEJEAP_0.pdf">denying Black and Latino students access to those courses</a>.” Herein lies the double-bind of many common “race-neutral alternatives.” Students from under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds who are <b>also</b> socioeconomically disadvantaged tend to be concentrated in school districts that do not offer access to foundational STEM coursework, as I discuss further in annotations below. <a href="https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-educational-opportunities-report.pdf">According to NCES</a>, 25% of graduates from schools where 25% or less of the students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL) had completed calculus, whereas this completion rate was only 9% among graduates from schools where greater than 75% of students were eligible for FRPL. Meanwhile, the subset of students from under-represented racial and ethnic groups students who <em>do</em> have notional access to these courses tend to be relatively more socioeconomically advantaged — because <em>you have to be</em>, in order to live in a school district that offers these courses — and therefore are not reached by alternatives that focus on economic and educational disadvantage <em>even as </em>they are routinely denied access to these courses. Students from these historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds are thus squeezed from both sides in a way that is not as true, in the statistical aggregate, for white and Asian students. most important for preparing students to study STEM in college34 In a study of more than 76,000 STEM majors, Radunzel et al <a href="https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581664">show</a> that success in earning a degree in a STEM field depends on both intrinsic interest and prior preparation. In recent years, there has been a great deal of progress made in awakening interest in STEM fields among students from historically under-represented and under-served backgrounds, but, as noted in the prior annotations, much less in improving preparation, which cannot be easily remediated after the fact. As I <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/we-are-reinstating-our-sat-act-requirement-for-future-admissions-cycles/#annotation-5">explained</a> in our test reinstatement post, we have no evidence that “bridge” programs like <a href="https://ome.mit.edu/programs/interphase-edge-empowering-discovery-gateway-excellence">Interphase</a> can “make up for” significant preparatory deficits in high school (although they have been empirically shown to have <em>other</em> considerable social and academic benefits). This was also found in Kidder & Gándara’s <a href="https://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/kidder_paper.pdf">study</a> of the UC system, which found that the Student Academic Preparation and Educational Partnerships (SAPEP) bridge programs established after Proposition 209 had great expense and limited efficacy at closing the gaps in preparation for the UC system. It should not be surprising that short-term enrichment programs cannot entirely compensate for long-term structural deprivation linked to race and class.

- This significant change in class composition comes with no change to the quantifiable academic characteristics of the class35 Here, as before, I am referring primarily to performance on high school performance and standardized tests, the key things we find to be predictive in evaluating <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/apply/prepare/foundations">preparation for MIT</a>. I know some readers may be surprised by this fact, because of the widespread misperception that race-conscious admissions pre-<em>SFFA</em> necessarily involved admitting unqualified students from under-represented backgrounds in order to achieve diversity. That widespread belief was untrue. As I told <em>MIT News</em>, in my time as Dean of Admissions, all admitted students have been required to demonstrate rock-solid academic readiness for the MIT education before we admit them. That is why we are not surprised that, in all the ways we can quantitatively measure, there is no difference predicted in the academic outcomes between the Class of 2027, which had the highest proportion of students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds in MIT history, and the Class of 2028, which has the lowest proportion of these students in decades. There may, however, be <em>qualitative</em> differences, which I address in the bullet point immediately below. that we use to predict success at MIT

- However, if MIT cannot find a way36 That complies with the new law. to continue to draw on the full range of human talent and experience in the future, it may threaten the qualitative strength of the MIT education, both by a relative reduction in the educational benefits of diversity and by making our community less attractive to the best students from all backgrounds.37 As I told <em>MIT News</em>, as MIT has become more diverse, more of the most talented students in the country from all backgrounds have chosen to enroll here, and they specifically tell us in surveys that it is because attending a diverse institution is important to them and they like how diverse MIT has become. Today’s students come from the most multiracial, multiethnic, multicultural generation of Americans that has ever existed; it is not surprising they prefer a campus that reflects these qualities. So another reason we care about diversity is because it makes us the strongest magnet of talent for the next generation of scientists and engineers and provides them with the best educational setting.

For a very long time, there has been no topic in college admissions more controversial than the consideration of race. In my sixteen years as Dean of Admissions, I have heard every complaint and critique you can imagine from every political, professional, and personal perspective. There are those who believe that MIT has cared too much about diversity, and there are those who believe we have never cared enough. There are those who believe we have been racist by using race-conscious admissions to enroll diverse classes, and those who believe we have been racist by reinstating our testing requirement. These viewpoints are so diametrically opposed, and so deeply held, that it can feel impossible to reconcile them and persuade people to find common ground.38 Even with all of the differences of opinion I outlined above, I think most MIT students and alumni can agree with the basic proposition that they learn best when surrounded by brilliant people from a wide variety of backgrounds, who are empowered by our education to bring their skill and insight to bear on to a broad array of scientific and social concerns. If we can hold onto that commonsense and longstanding belief, then I think we can get somewhere together.

So I’m not going to attempt that in this post.

Instead, I want to tell you what I believe.

I believe that every student we have admitted on my watch was admitted because they were demonstrably well-qualified for, and well-matched to, the MIT education, and because we saw how their presence in the class would improve the collective experience for everyone. We have long valued potential over pedigree,39 This phrase comes from the <a href="https://www.mit.edu/values/#:~:text=Belonging%20and%20Community">MIT Values statement</a>. As we say in our <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/about/about-mit-admissions/#:~:text=and%20our%20institution.-,We%20are%20egalitarian,-For%20us%2C%20egalitarian">policies</a>: “Before any applicant is accepted, that person’s application passes through at least five distinct stages of review and is evaluated by several different committees composed of admissions officers and faculty reviewers. This process, which is unique in its particular design and has held fast for more than 50 years, guards against an individual’s biases, preferences, or familiarity with a given applicant swaying a decision unfairly. All applicants meet the same demanding standard, regardless of legacy status, donor affiliation, or athletic recruitment. We have no quotas by school, state, region, or socioeconomic background, but we also value diversity and believe that it contributes to the merit of each class.” and our egalitarian approach40 For example, work from Chetty et al <a href="https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/CollegeAdmissions_Paper.pdf">demonstrating MIT’s lack of preference for wealth in its selection process</a>, and finding that <a href="https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23618/w23618.pdf">our process contributes substantially to socioeconomic mobility</a>. According to the <em>New York Times</em> <a href="https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/24/upshot/ivy-league-elite-college-admissions.html">coverage of the research</a>, “⌈MIT⌋ stands out among elite private schools as displaying almost no preference for rich students.” I was quoted in this article as saying, as I will repeat here now: “I think the most important thing here is talent is distributed equally but opportunity is not, and our admissions process is designed to account for the different opportunities students have based on their income...It’s really incumbent upon our process to tease out the difference between talent and privilege.” to evaluating excellence across contexts41 This is another way diversity matters: because in different soil, different plants bloom, and so you need an open mind, above a high bar of academic preparation, about what “excellence” looks like. As my predecessor B. Alden Thresher once <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/college-admissions-in-the-public-interest/">wrote</a>, “the process of admission to college is more sociologically than intellectually determined...to understand the process, one must look beyond the purview of the individual college and consider the interaction of all institutions with the society that generates and sustains them.” That is why we still consider many kinds of diversity: prospective fields of study and areas of research, extracurricular activities and accomplishments, as well as economic, <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/reaching-for-the-stars/">geographic</a>, and educational background. We are just no longer permitted to consider race. has enabled us to select students whose potential might have been otherwise masked or limited42 This language borrows from the charge to the 1968 Task Force; we revive it to hold in focus students whose intellectual star burns bright and hot to our sensitive instruments even if, to the naked eye, it is obscured behind the interstellar dust of unequal opportunity. I should note here that the Class of 2027 — admitted last year under our <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/we-are-reinstating-our-sat-act-requirement-for-future-admissions-cycles/">reinstated testing requirement</a> — had the highest proportion of students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds in MIT history, because universal testing helped us identify objectively well-qualified students who lacked other opportunities to demonstrate their preparation and potential. The decline in students from these backgrounds for the Class of 2028 thus cannot be attributed to our reinstatement, but instead to the Supreme Court’s constraint on the use of race. Standardized tests are not the only way to demonstrate otherwise masked or limited potential, but in the context of <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/we-are-reinstating-our-sat-act-requirement-for-future-admissions-cycles/#annotation-10">broader inequality of opportunity in K-12 education</a>, they remain an important tool. without compromising the quality of the class. I believe this not only because I have read applications, seen what we demand for academic standards,43 When I was admitted, in 1982, the admit rate was 33%. It was so long ago that things like SAT scores, retention rates, and graduation rates were not tracked or recorded; however, anyone from that generation can tell you that many students entered MIT without sufficient preparation, as evidence by how many did not succeed or graduate. Now, the admit rate is ~5%, the 25th percentile SAT math score is 780, and we admit no students unless we are confident in their academic preparation, as demonstrated by a first year retention rate of 99% and a six year graduation rate of 93%. I know some alumni and faculty from my generation sometimes grumble (because they grumble to me!) that the MIT education has been watered down; the data clearly shows the opposite is true in every way we can reasonably measure. There is only one way into MIT, and it is a very hard road with an absurdly narrow gate in terms of academic preparation. And there is no question in my mind that the students we are admitting today are, in aggregate, more academically prepared for our rigorous education than at any time in MIT’s history. and advised generations of first-year students, but also because as MIT has become more broadly diverse, academic outcomes have improved for all students44 As measured by things like performance at MIT, retention after the first year, and graduation within six years. These are not the only outcomes that matter; they don’t include things like research innovations or social impact. They are, however, the things we can straightforwardly measure as a baseline set of academic outcomes. and we have simultaneously become more attractive to the most talented students from all backgrounds.45 I <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/mit-after-sffa/#annotation-37">mentioned above</a> about how strongly we see this signal for the current generation. Since I’m already dating myself by comparing 33% admit rates to 5% admit rates, I’ll also mention the yield rate — the percentage of students to whom MIT offered admission who decided to enroll at MIT — was 58% in 1982, and is 86% now. It is clearly the case that MIT is a more attractive school to attend today than it was for much of its history, and our survey responses suggest that its increasing diversity plays a significant role in that. As in metals and magnets, the strongest materials are alloys, where many different materials are mixed together to achieve composite strength that can collectively withstand the greatest challenges. The same is true of our student body.

I believe that MIT’s longtime strategy of using standardized tests to recruit students and validate academic preparation,46 As I explained <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/we-are-reinstating-our-sat-act-requirement-for-future-admissions-cycles/">when we reinstated testing</a>, our research — which has been ongoing since the 1970s — shows that we cannot reliably predict academic success at MIT without relying on standardized testing, and that it further helps us to identify objectively well-prepared students who do not have access to advanced math and science coursework at their high schools and is in this respect <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/we-are-reinstating-our-sat-act-requirement-for-future-admissions-cycles/#annotation-10">less racially unequal than other predictive measures</a> we have so far been able to find. Given this, we do not believe that removing our testing requirement would help diversify MIT after <em>SFFA</em>; indeed, it would likely do the reverse. More generally, I’d note Professor Sue Dynarski’s <a href="https://www.brookings.edu/articles/act-sat-for-all-a-cheap-effective-way-to-narrow-income-gaps-in-college/">report on using universal testing to identify and recruit</a> high-achieving low-income students who would have otherwise not attended college. However, I should <em>also </em>note that this approach has been <a href="https://www.goodwinlaw.com/en/insights/blogs/2024/06/college-board-settles-for-750000-penalty-for-sharing-and-selling-student-data-in-violation-of-new-yo">challenged by new privacy laws</a> which — while doubtless well-intentioned — make it harder to individually recruit standout students from unexpected places. combined with the narrow consideration of race before SFFA to draw from the full breadth of human talent,47 As I said above, we can and do draw on other forms of diversity, as we actively seek out <a href="https://news.mit.edu/2023/3-questions-stuart-schmill-mit-admissions-stars-college-network-0404">rural students</a>, students from most countries of the world, students from families with less economic and social capital, and students from a range of academic interests and professional aspirations. We are simply no longer permitted to consider race among the kinds of breadth we can intentionally draw on. had long helped diversify and strengthen MIT, as well as the industries and institutions downstream of the Institute. I believe this because according to the American Society for Engineering Education, over the last decade48 While this statistic was only tabulated for the last decade for the purposes of this blog post (in part because earlier data collection was spotty and from a smaller number of schools, and in part because this time period consists of most of my time as Dean so I feel comfortable speaking on it) the basic trend of us being a top ~20 institution overall, and the top private institution period, appears to hold true for as long as the ASEE has been collecting and publishing data. The last decade of MIT graduates also coincides with the career of <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/blogs/author/dldj/">David duKor-Jackson</a>, who began in 2009 as as our Director of Minority Recruitment in one of my earliest and best hires as the new Dean of Admissions; today, David is our Director of Admissions. David — who himself holds a science degree from the Florida Institute of Technology, taught high school biology for a time, and understands well what is demanded of our rigorous education — deserves a great deal of credit for pioneering initiatives and processes that helped enable these recent outcomes. MIT has graduated more engineers from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds49 For the purposes of the ASEE data, this is again students who are classified as Black, Hispanic, or Native American/Pacific Islander. Note that because ASEE uses federal <a href="https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/">Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) data</a> — which uses legacy racial categories, and classifies most self-reported biracial or multiracial students as a separate category of “Two or more races” — this is likely a substantial <b>undercount</b> relative to how students would self-identify, but in a way consistent across all universities. Unfortunately, the limitations of the IPEDS data does not allow us to report on other under-represented ethnic groups, particularly those included within the Asian or “Two or more races” categories. than any other private college or university (and the vast majority of public universities) in the United States.50 As well as the vast majority of public universities. According to data collected by ASEE from 478 ABET-accredited colleges or universities, MIT ranks #25 overall in absolute number of individual Black, Hispanic, and/or Native students who graduated with engineering degrees from 2013-2023, the most recent decade available. All those ranking above us in absolute terms are large public universities; most (though not all) educate a much lower proportion of students from historically under-represented backgrounds among their engineering graduates. These students have gone on to thrive as leaders in academia,51 According to the most recent <a href="https://www.rti.org/sites/default/files/documents/2023-11/Exploring%20the%20Education%20Experiences%20of%20Black%20and%20Hispanic%20PhDs%20in%20STEM.pdf">NSF data</a>, from 2010-2020 MIT graduated more Black STEM PhDs than any private university that is not an HBCU, ranking 14th in the nation overall across all universities of any status or size. During the same time range, MIT also graduated more Hispanic STEM PhDs than any private university, ranking 8th in the nation overall across all universities of any status or size. industry, government, and many other fields. We should be proud of this legacy and the alumni who constitute it, and we must find ways to continue to educate future generations of diverse STEM leaders in this new legal landscape.

I believe that the answer to the question of “how much diversity is necessary to benefit the MIT education?” is fundamentally qualitative, not quantitative.52 As it is put in the <a href="https://mitadmissions.org/policies/#diversity">CUAFA diversity statement</a>: “How much diversity is necessary to achieve our goals? Every student should feel that ‘there are people like me here’ and ‘there are people different from me here.’ No student should feel isolated; all students should come into contact with members of other groups and experience them as colleagues with valuable ideas and insights.” I understand that this answer may frustrate the characteristically analytical MIT mind, but it is important to understand that, as I have said before, we do not, and have never, operated by target or quota. However, I also believe that when there are now fewer African-American first-years enrolling at MIT than when I was a freshman more than forty years ago, that cannot possibly be the right outcome for our community; not in a country as large and increasingly diverse as ours, and not at an institution with our history and our values. While we must comply with the law, we also must also find a way to hold our pathways to leadership open,53 It’s worth noting that the majority opinion in <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grutter_v._Bollinger"><em>Grutter</em></a> — the primary precedent governing our work before the <em>SFFA</em> case — also held that “because universities...represent the training ground for a large number of the Nation’s leaders, the path to leadership must be visibly open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity” as an additional compelling interest. Given MIT’s role as a major training ground of the nation’s scientific and technical leadership, we have historically taken this responsibility particularly seriously. In <em>SFFA</em>, however, the Court held that while the Grutter interests “are commendable goals, they are not sufficiently coherent” to justify the consideration of race. or we may all experience long-term downstream consequences concentrated in the already-unequal area of STEM,54 As I write this, I do not know what has happened at other universities, and I do not want to claim that this decline at MIT will alone account for dramatic changes in the academic and industry ecosystem. However, Professor Zach Bleemer <a href="https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/137/1/115/6360982?guestAccessKey=95fdbb6a-a289-4d5e-850f-cc3e162b0426&login=true">shows</a> that Proposition 209 created a durable “cascade effect” within California that discouraged historically under-represented students from applying to university, while pushing those who <em>did</em> enroll in STEM majors out of the STEM workforce <em>regardless of their academic performance</em>. This is also consistent with Dr. Chelsea Barabas’ <a href="https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/97992">research</a> demonstrating as-yet intractable insular recruiting practices that steered companies away from universities that educate more under-represented students. Given this research, and because we know that MIT has been one of the largest national sources of students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds who hold STEM degrees, we are concerned that the decline we see here may have outsize impact well beyond university admissions at our small institution, in addition to whatever effects there are across the national landscape. where we most need the creativity and insight generated by broadly diverse teams55 It is perhaps worth noting here that, in addition to Ronald Burt’s classic article on the <a href="https://www.bebr.ufl.edu/sites/default/files/Burt%20-%202004%20-%20Structural%20Holes%20and%20Good%20Ideas.pdf">diverse origins of good ideas</a> I noted in a prior annotation, <a href="https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15534225/">contemporary research on intelligent agents</a> suggests that groups of problem solvers with diverse functional approaches outperform agents with more specialized individual ability. inventing the future of the nation and the world.

These convictions underpin our recommitment to the institutional mission — articulated in the message that President Sally Kornbluth sent the MIT community today — that Paul defined for the Task Force56 The following quote contains sentences concatenated from Paul’s remarks as recorded from the November 1968 and April 1969 faculty meetings, as well as sections of the 1969 President’s Report that summarize them. more than half a century ago:

The Institute has much to offer in terms of the kind of education that elevates, empowers, and liberates people, and it seems to me that we must not fail to make those opportunities accessible on a broad scale [through] the development of programs [that include] persons whose promise, talent, and potential have been masked or limited by second-rate educational experiences, by poverty, or by social prejudice and discrimination…[We must recognize] the limitations of any educational environment that fails to come to grips with problems growing out of a long history of inequality of opportunity [and our] responsibility to contribute toward the ultimate resolution of the social crisis which divides this nation and imperils its future.

As I told MIT News, throughout the last year, my team and I have been meeting with student leaders, faculty committees, and President Kornbluth and her team to explore what we can do to uphold this mission while complying with the law. In addition to the expanded recruitment and financial aid initiatives we launched last year with their support, we have also created new pathways for students to demonstrate their math and science preparation beyond what is locally available. These initiatives proved necessary, but not sufficient; we are dismayed, but not discouraged. We believe, as generations of MIT’s leaders have, that no problem is too hard for us to tackle as a team.

We do not know, yet, where these initiatives will take us. When navigating unknown territory, we must often rely on compasses over maps: guided not by a well-trodden path to a certain destination, but instead oriented by the powerful magnetism of our longstanding institutional conviction that MIT becomes, as Paul put it, a stronger, more effective place as it draws on the full range of human talent and experience.

This compass point remains, as I wrote last year, “the North Star by which we will steer through uncertain waters ahead.” Like any long, hard voyage, we will need favorable winds, an able crew, and a steady hand at the tiller to make the passage together. My four decades at MIT give me confidence that no matter what else is happening in the world, on this matter, we will all be rowing together, hard against the current, until we reach the shore.

- My parents — who were born and raised in the tenements on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, speaking Greek and Ladino at home — did not attend college, and did not accompany me to campus. In fact, the first time they set foot on the MIT campus was to see me graduate, four years later. back to text ↑

- I remember that when I got my admission letter in the mail, at first I was excited, but almost immediately after felt the concern that I had been admitted by mistake. And today, at our admitted student program each spring, the number one question I get from students is some version of: “How did I get in?” Many of our students feel this impostor syndrome prospectively to some degree or other, and to them I say — unequivocally — that every student we admit belongs here, period, and has demonstrated the academic and personal qualifications to thrive at MIT and beyond. back to text ↑

- I later learned the Class of ‘86 had over-enrolled by several dozen students, due to high yield rate that caught the Admissions office off guard. I only knew it was a forced triple decades afterward, once I started working in admissions - we all just thought it was supposed to have three people in it. back to text ↑

- ...despite the fact that they liked to spin records late at night while I was trying to wake up to be on the river at 6AM for crew. That said, serendipity reigned: the three of us briefly ran a DJ business together after graduation. back to text ↑

- It is hard to exaggerate the degree to which Paul — who was not a tall man — towers in MIT history, alongside his wife Priscilla, after whom our Center for Public Service is named. After earning his bachelors, masters, and doctorate in electrical engineering, he served sequentially as Professor, Dean of Engineering, Associate Provost, Chancellor, President, and finally Chair of the MIT Corporation, our board of trustees. The house occupied by the President of MIT is named after them, as is the walkway across campus along which he and Priscilla would daily wander, greeting students, faculty, and staff along the way. In 1997, when he stepped down as Chair of the MIT Corporation, his successor Chuck Vest said in a speech, “Is Paul the image of MIT, or is MIT the image of Paul? Both, I suppose. Indeed, he personifies our institution — integrity, loyalty, tenacity, and, of course, his championing of our meritocracy.” Everything we have done in MIT Admissions — before and during my tenure as Dean — has been in this tradition set out by Paul and the students of the Task Force (below) more than a half-century ago. back to text ↑

- Crew is a sport I didn’t even know existed before I arrived, but would become the center of my world for the next twenty years. After four years as an MIT undergraduate, I became the MIT crew coach for thirteen more, and still compete annually at the Head of the Charles. back to text ↑

- Jim taught me 2.03: Dynamics; he was an incredible instructor, lecturing without notes while making complex topics easy to grasp; his skill as a teacher made this probably one of the few courses that I understood all the way through. Later, as part of his hunger strike for more diversity among the MIT faculty, Jim once memorably described the kind of diversity to which he thought MIT should aspire: “a broad intellectual, sociological, action-oriented and multi-ethnic community.” This vision has stayed with me ever since. back to text ↑

- “Introduction to Design and Manufacturing,” now known as 2.007, and the class that inspired FIRST Robotics, which Woodie would co-found with the inventor and entrepreneur Dean Kamen in 1992. I took it with my friend and classmate Megan Smith, who would go on to run GoogleX and PlanetOut, and later became the Chief Technology Officer of the United States. Like FIRST today, 2.70 was a great example of how people with different backgrounds can come up with different ways to solve problems, as Woodie once said in an interview; I remember I was the only person with my design that year (I lost in an early round of the 1984 competition, but to the eventual winner, which softened the blow somewhat). back to text ↑

- 2.72 was, then as now, Elements of Mechanical Design, which taught students how to synthesize, model and fabricate a design from scratch and subject to real-world constraints. Ernesto — who was born in Cuba and frequently consulted with the State Department on engineering education in Latin America — was a legendary instructor and inventor, most notably of many breakthrough medical and assistive devices; like many other of his students, I was in awe of his mission-minded technical creativity. back to text ↑

- As Matt Damon’s MIT-janitor character says to a rival from Harvard in Good Will Hunting, “You wasted ⌈your tuition⌋ on an education you coulda got for $1.50 in late fees at the public library.” But of course — and as Damon’s character later learns from his therapist, played by Robin Williams — what you can’t get from a book are the humans you meet along the way, and what they can teach you. back to text ↑

- I cannot emphasize enough the centrality of learning to collaborate with others who are different from you as a core feature of our education. I briefly went to General Motors and was a design engineer for a little while after graduating from MIT. The engineering part of it was frankly simple, and I could have learned it anywhere. The challenging part of that job was working with people on big, complex projects under pressure. So that is the part of the MIT education that I think was the most valuable for me: it was all project-based work that we did, because I learned how to to generate new ideas and execute on them with other people who had different ideas and perspectives and experiences from mine. back to text ↑

- As we argued at length in a joint industry-academia amicus brief with Stanford, IBM, and Aeris Communications, the educational benefits of diversity are a consistent empirical finding across a variety of disciplines. More intuitively, anyone who has ever worked on any creative problem solving knows that nothing kills creativity and innovation like a monoculture, while a meritocratic pluralism of brilliant and diverse perspectives is a dynamic source of new ideas. In his classic article “Structural Holes and Good Ideas,” the sociologist Ronald Burt studied how successful innovators in business are often people who “bridge” homogenous groups, because they “have earlier access to a broader diversity of information and have experience in translating information across groups…⌈providing⌋ a vision of options otherwise unseen.” Any MIT alum will recognize the Institute as a training ground for these kinds of bridge figures. back to text ↑

- As I told MIT News, in my time as Dean of Admissions, all admitted students, from all backgrounds, have been required to demonstrate rock-solid academic readiness for the MIT education through their performance in high school and on standardized tests. And in recent years, as MIT has grown more diverse, collective academic performance has improved, as have retention and graduation rates, which are now at all-time highs for students from all backgrounds. I emphasize this essential fact because many people have told me over the years that they think MIT ought to only care about academic excellence, not diversity. But this is a false choice, because every student we admit, from any background, is already located at the far-right tail of the academic distribution. back to text ↑

- Though not only science and technology, and certainly not for their own sake. As Paul said in his inaugural address as MIT’s President in 1980, “We continue to hear the complaint that...many of our human and social ills are the direct result of unanticipated and deleterious artifacts of technology, foisted upon the world by technicians with tunnel vision...What is clear, however, that the future development not only of this nation, but of the world, is inexorably tied to continued scientific progress and to the humane and thoughtful applications of science...What is needed is not a retreat from science and technology, but a more complete science and technology. We must strive to develop among ourselves, among our students, and in the public at large, an understanding of the fact that engineering and science are, by their very nature, humanistic enterprises.” back to text ↑

- As the Lewis Report described the purpose of the MIT education all the way back in 1949: “We believe that the mission of the Institute should be to encourage initiative, to promote the spirit of free and objective inquiry, to recognize and provide opportunities for unusual interests and aptitudes; in short, to ⌈develop⌋ individuals who will contribute creatively to our society, in this day when strong forces oppose all deviations from set patterns.” The modern MIT mission directs us to “educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century.” back to text ↑

- The best guide to this history is Dr. Clarence Williams’ indispensable Technology and the Dream: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT, 1941–1999. Clarence and I first became friends in the 1990s, when I was the head crew coach, and he was Special Assistant to the President of MIT for Minority Affairs. Back then, I volunteered coaching a rowing team of teenagers from the Mandela Apartments in Roxbury. In addition to borrowing some of our boats, I opened the MIT Boathouse to them so they could train alongside MIT undergrads, and they eventually became the first team of all Black and Hispanic students to compete in the Head of the Charles, for which they were celebrated by ABC’s World News Tonight. Clarence, who was honored earlier this year with a lifetime achievement award at the 50th Anniversary MIT MLK Celebration, was a central advocate of this initiative and helped manage the relationships and build support; we saw it as a way that MIT could share its intellectual, social, and material resources with the community, in keeping with our mission and our land-grant charter. Later, when I ran the Educational Council, I shared an office in N52 — the old MIT Museum building — with Clarence, while he was finishing work on this book. “MIT served as a pioneer in the late 1960s and early 1970s, developing admissions criteria so that black students would get an opportunity to attend this institution,” he wrote in its introduction. “Among schools of engineering and science, MIT’s criteria became a model for other institutions to increase the numbers of young minority scientists and engineers.” back to text ↑

- Described by the 1969 MIT President’s Report as “a remarkable demonstration of student initiative at its most creative and sophisticated level,” as so many of the student initiatives in this area have been in our history. back to text ↑

- Among them a young Shirley Ann Jackson, who would go on to become first African-American woman to earn a doctoral degree from MIT; she later ran the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and served as the 18th President of RPI. The MIT Black Student Union she helped found was crucially involved with recommending and starting the Task Force, and led many of its key initiatives. back to text ↑

- When asked, at a faculty meeting in 1969, why MIT was embarking on these efforts to expand opportunity, Paul said: “⌈S⌋ome of those who have in recent months commented on this program have expressed concern that the Institute has embarked, for reasons that are seen to be essentially political, on a course that will lead it away from its responsibility for the education of an elite, and will compromise its capability and its contributions in this respect. This view seems to me to overlook several important aspects of both the Institute’s traditional role, and its responsibility to the society in which it functions. Over most of its history, MIT has provided, in educational terms, the skills, knowledge, and qualities of mind that have been required to work out solutions to the problems posed by our developing society and to enable individuals to become more effective, more mobile, in that society...it seems to me that we must not fail to make those opportunities accessible on a broad scale by getting hung up on a narrow, self-serving, conception of education for an elite.” back to text ↑

- Specifically, the Task Force directed the admissions office to begin a nationwide talent-search for students from historically under-represented racial and ethnic backgrounds who might do well at MIT. John Mims — the first African-American admissions officer at MIT — developed an at-the-time innovative plan to individually recruit students who had performed well on the PSAT or SAT; his initiative immediately octupled the number of admitted students from historically under-represented backgrounds. In 1996, Paul Gray told Clarence Williams: “We did then what we really still do to increase the flow of applicants, that is, we send material by mail to all those high-school students who have taken the SAT’s who at that time indicated that they were African-American—now other minorities are included—and who have scores in the range that at MIT might make sense. A little brochure went out that first year that was produced by the task force...and resulted in sort of a ten-fold increase in the number of minority applicants. That’s been the core of the effort ever since.” Dr. Sylvester James Gates — a member of the first class of students recruited via this initiative — told Williams: “It was almost like an athlete being recruited to go to college to play ball,” except for a STEM education. back to text ↑

- Among them, an early initiative to guarantee sufficient grant-aid scholarships to Black undergraduates in the 1970s so that they could attend MIT without having to take out loans, which was especially salient given the contemporary issues with redlining. Today, all admitted students from all backgrounds receive scholarships that meet 100% of financial need without any expectation of loans. back to text ↑

- I should note that in addition to of the specific efforts of the Task Force, MIT faculty also launched their own initiatives, creating new areas of teaching and research in in urban affairs, offering pro bono legal services to Cambridge minorities, and cofounding the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO) the largest and second-longest continuously running voluntary school desegregation program in the United States. back to text ↑