Question me an answer. by Sam M. '07

I try to help somebody, for the first time ever.

PROPOSTION. You’ve been reading this blog all this time without ever getting to know me. I mean, the real me. On Friday or thereabouts, I’m going to do an entry introducing myself in a survey-type format. If you have any personal questions you’d like me to answer, just leave them in a comment and I’ll let you know.

DID YOU KNOW? The entry title comes from some fantastic old 1970’s movie that my grandfather had on one afternoon while I was growing up. All I remember is a guy in a paisley suit dancing around on a dock with a Vietnamese children’s choir and singing “even though your answer may be wrong, my question will always be right!” as they sing things like “1776!” and he replies “When did Columbus sail the ocean?” and the song goes on like this for like 23 minutes, because there was a tap dance break or something in the middle, and at the end of the song the Vietnamese children are so annoyed by this guy that they push him into the river, which he totally deserved, and he just sits there splashing for a while and the harp plays festive arpeggios that lead us into the next scene. Has anybody seen that one?

But I digress.

ANONYMOUS QUERY! “You’re a chemical engineer student, right? I really love chemistry, and I also love building and planning things (I make my own little doomsday devices)…so Chemcials + engineering…can you tell me what a real chemical engineer would do?”

I’ve always been meaning to do the “how does a chemist differ from a chemical engineer?” entry, and now you’ve gone and given me an excuse. Look what you’ve done now.

The short answer is the old adage “Chemical engineering is the practice of doing for a profit what an organic chemist does only for fun.” Well, that’s not entirely accurate, but it is true that the work done by a chemical engineer usually vastly differs from that done by an organic chemist. Chemists usually concern themselves with work at the molecular level–characterizing a new metal-ligand catalyst via spectoscopy (5.04), finding the best set of reactions to synthesize a particular drug (5.13), or determining the exact geometry of a molecule’s electrons during a chemical change (5.60 and 5.61). A chemical engineer isn’t going to be concerned so much with exactly what molecules look like or how they react, but rather what their gross properties are and how to optimize these reactions for research and industrial applications.

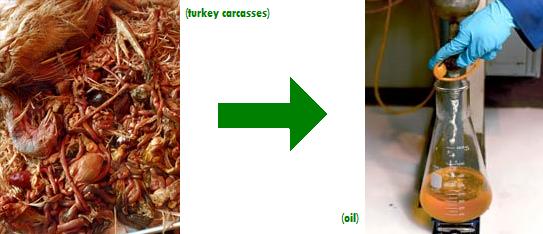

For example, as you might know by now, my job as a chemical engineering researcher is to turn turkey carcasses into oil.

Now, my grad student Andy and I already know how the turkey carcasses turn into oil, kind of… you just heat them to 500 C, magic happens. And we know what’s causing a problem in this process–the normally-delicious Maillard reaction is forming giant brown-black polymers akin to bread crust in the 250 C reactor. However, to solve this problem, we’re not really looking at the Maillard reaction at the molecular level. We’re considering it basically only in the context of glucose + glycine => ugly black polymer. Rather than trying to determine theoretically how we might prevent the Maillard reaction, we’re varying the parameters of the reactor used and measuring the output and composition of the products. Our work is not so much theoretical as practical, and the questions we ask are not “What cofactor could be added to slow down this reaction?” but “How can we detect the presence of glucose and glycine in our final reaction mixture?” or “How can we best model the fuel company’s reactor in our design?”

A lot of chemical engineering is data analysis, it seems. This semester I’ve spent a good four or five hours poring over Excel spreadsheets every week. MATLAB is also a major component of many Course X classes, much to the chagrin of programming-averse sophomores. Accordingly, the classes in chemical engineering emphasize real-world problem solving and situation analysis just as much as they do textbook examples. In 10.301: Process Fluid Mechanics, half the course was spent fitting viscosity data to smooth curves and verifying particle settling rates, while the other half was spent in a theoretical discussion of shear stress. This week in 10.302: Transport Processes, I have just about the most awesome problem ever to solve, involving the design of a ceramic plasma coating implement that operates at 10,000 K with a convective coefficient of 30,000 W / m K. Unlike some chemistry classes, in which you’re just oxidizing your primary alcohols all night, I can always see exactly how what I’m learning might be applied in industry.

And what does a chemical engineer do in the real world? Well, according to career fair, a chemical engineer might work for an energy company like Shell or BP, or a pharmaceutical company, which would be just perfect with a degree in the newly-created Course 10B: Biochemical Engineering. Heck, maybe they’d even work for a chemical company. One thing that’s pretty cool about any engineering major at MIT is that you end up getting, through your required classes, quite a bit of experience with other types of engineering–in particular, a lot of what you see in Course 10 relates closely to Course 2: Mechanical Engineering and Course 3: Materials Science and Engineering. As a result, it’s possible to find a job with chemical applications in areas that would initially seem to be only tangentially related. So, in conclusion, Chemical Engineering at MIT is the most perfect major at any college, ever and opens a million doors to boundless possibilities limited only by your imagination.

Okay, hope that helped, Anonymous… if that it your real name.

BONUS! More adventures in German grammar.

Yesterday in German I we learned how to say number above 20, all the way up to 999,999. Then somebody asked how you say “ten to the sixth.” “Zeun hoch sechs.” apparently.

We’ve got our first major test am Donnerstag, and today was essentially a review for that occasion. About half the class was confused about when to use the accusative case for articles and pronouns until one student, who had spent last summer interning in Germany as part of the MISTI program, came up with this gem of a mnemonic…

Nominative: “Er ist ein student.”

Accusative: “Er isst einen student.”

and x^2 is “x quadrat” and the square root of x is “wurzel aus x” (cubed is “dritte wurzel aus…”) It’s really awesome that you’re learning German. What’s your favorite word in German? About how many students take foreign languages at MIT? What other languages besides German does the institute offer?

w00t!! Es gibt deutsche Klassen an MIT! Sind Fremdsprachenklassen f

My question for the survey: Did you know your initials spell S-A-M!?!?!

Yeah, so uh, what’s your favorite resturant in Boston? Do you like Indian food? What’s your favorite sport?

I read in the paper the other day that the board of education in Harrisburg is pro-intelligent design. Are you?

BoE in Harrisburg is pro ID? I live in PA, that is so not cool!

Response to big section about chemical engineering, just boiled down.

Rather, a question I guess. So, you have your chemical reaction going on, turkey carcasses + heat etc –> oil + malliard byproduct. Your job as the chem. engineer is to fool around with how you carry out the reaction to minimize the ugly malliard, but then you also design the best device to rid yourself of this byproduct? That sounds fun

Who in the world could be pro-intelligent design? I mean, man, if you look at it, intelligent design simply presupposes the supernatural for anything that can’t be explained. Isn’t this being adopting a religious overtone for the world that we’ve already recognized as being governed scientifically? That’s way not cool… those guys in Dover ought to be re-educated.

Ooops.. sorry about that.

Sam: who was your favorite TA and why?

Dear Sum1: Based on my experience, I’d say around 15-20% of MIT undergrads take foreign languages. The classes are a little larger than that, though, because grad students can also enroll in the same classes. MIT offers French, Spanish, German, Japanese, and Chinese. You can also cross-register for pretty much any language you can think of at Harvard, but to be honest, scheduling a language class at Harvard can be a little tricky (you most often have to commit to two semesters, and winter break/spring break/final exams rarely coincide).

Dear Another Anonymous: That is exactly correct, and far more elegantly put than I could have managed. You have a felicitous gift for composition.

Dear Nakki1: I think you asked if there is a language trequirement for graduation. I think. Nein, there is no such requirement. However, you can use language classes effectively to navigate the very tricky HASS (humanities, arts, and social sciences) “distribution” and “concentration requirement.” Unfortunately, this margin is too narrow to contain a full explanation of those requirements

Dear Mike: Not really Harrisburg… Dover Area Schools. It’s like an hour and a half from Harrisburg, but you can’t really label an article as coming from “Amish Country, PA.” More on this intelligent design business later