My First Academic Conference by Nisha D. '21

and also things I have learned about publishing research in the past few months

During election week, among all the chaos, I got the opportunity to attend something very cool: my very first academic conference! And also as of this week, I am officially a published researcher! WOOOOOOOO!!!!! I’m on Google Scholar and everything!

I submitted some of my research to CHI PLAY 2020, an “international and interdisciplinary conference for researchers and professionals across all areas of play, games and human-computer interaction (HCI)”. Angsting over this research was a long and arduous process that took up a lot of my spring and summer, but I made it! So in this blog post, I thought I’d document the process of my first research submission, and talk about some of the things I’ve learned about publishing research in general over the last few months.

As a disclaimer, I don’t speak for all fields – publishing in human-computer interaction probably works very differently than publishing in medical research, for example!

Doing the Research

Obviously, this *should* be the first step. For me, my research is the UROP project that I’ve been working on for almost two years now (making games is hard oops). It derives from my grad student’s research on playing creativity games with robots, and she’s written a few papers01 Google <em>Can Children Learn Creativity from a Social Robot?</em> for a representative example on how children actually emulate the creative expression of a robot, directly making their actions ‘more creative’.

Now this is pretty cool, because it means that embodied social robots can stimulate creative expression in children if programmed to behave in a way that scaffolds children’s creative behavior. My original task was to see if this same logic would hold for stimulating creative problem solving in children, and my original UROP project was to make a sandbox style game where children could place various objects to traverse through the level, and there are ‘creative’ and ‘non-creative’ ways to do this.

Unfortunately, I didn’t finish this game fast enough for my grad student to include in her thesis (oops), so after a while, she had me take it in whatever direction I desired. Originally, I had landed on the idea of having the social robot play different NPC (non-player character) roles02 There are lots of roles that a non-player character can take; a peer, a supporter, an opponent, a navigator, etc. I had been referring to <em>Autotutor and Family: A Review of Seventeen Years of Natural Language Tutoring</em> within the game, and this is the angle I was working on for quite a while. I still have an entire document of research notes about it. And with this in mind, my grad student was going to have me submit to the Student Game Design Competition in CHI PLAY. The SGDC is a ‘track’ within the CHI PLAY conference, and I’ll talk more about that later.

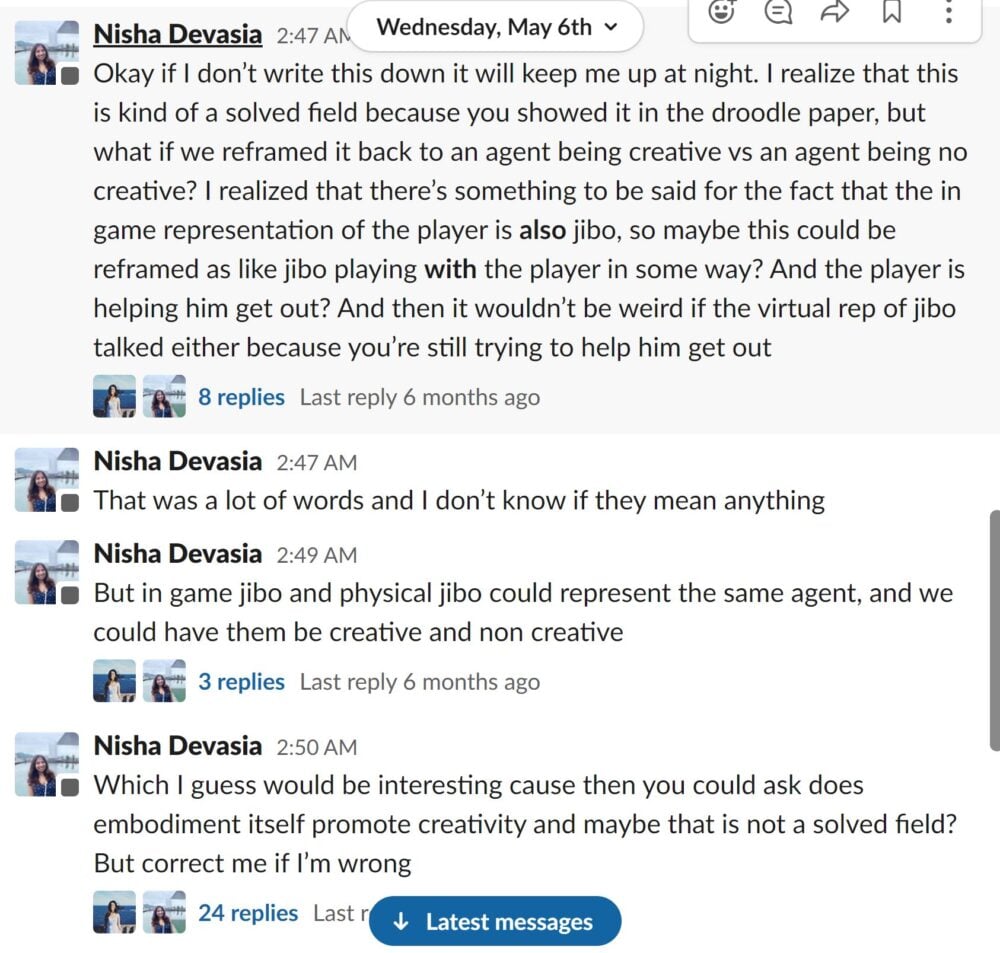

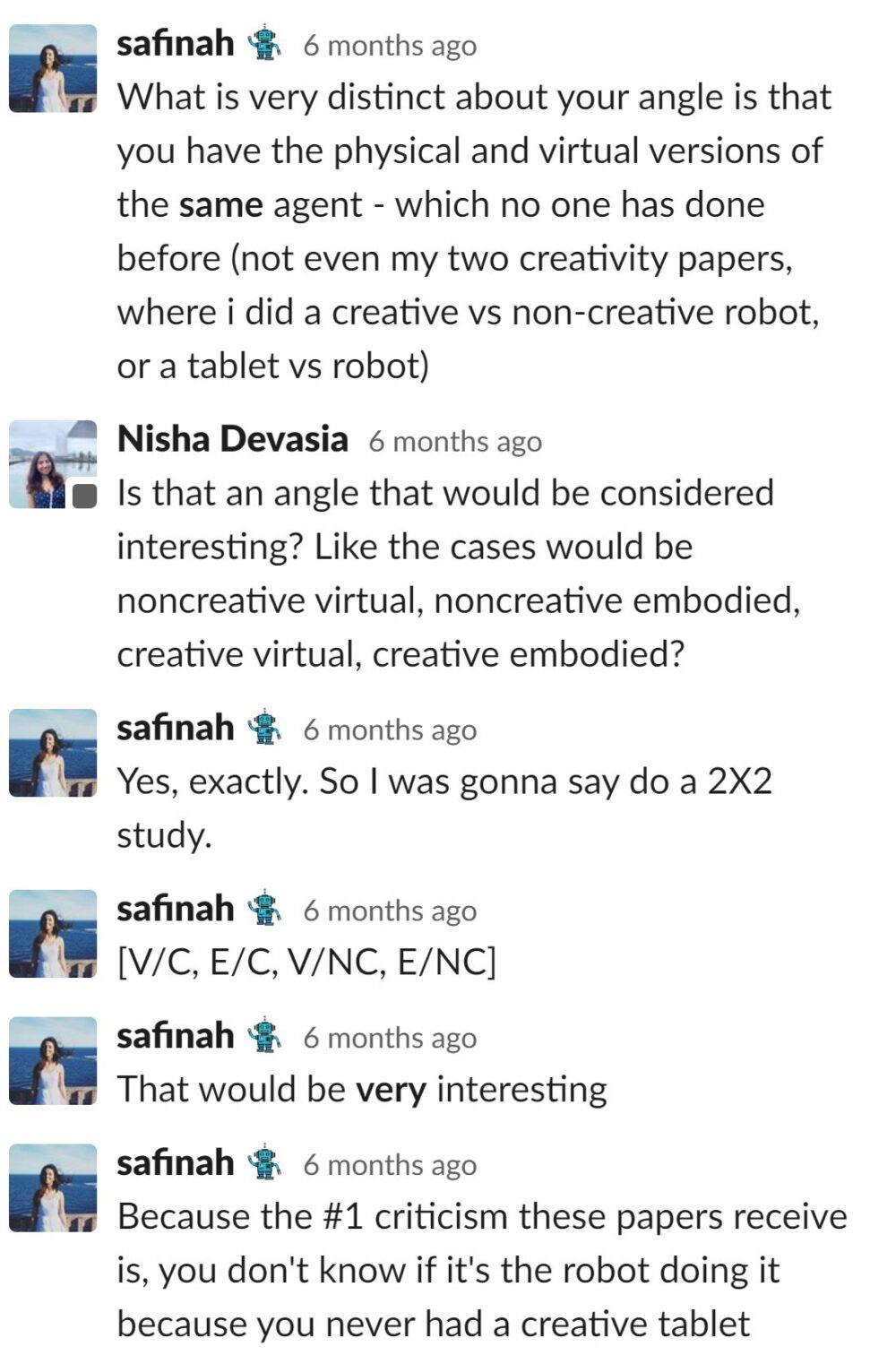

But at some point, before I started actually writing up the paper, I had a reasonably big brain idea, which I actually found documented in my Slack chat with my grad student.

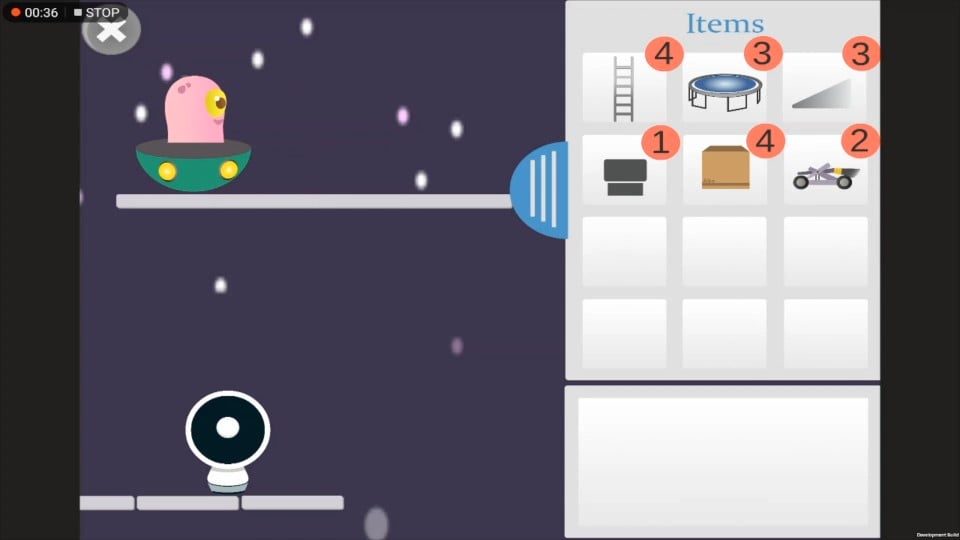

Confused? Well, basically, I was asking my grad student if *embodiment* (the fact that a robot has a physical body) has been shown to promote creative expression. Observe that my game looks like this:

…and Jibo, the robot that we were using as the actual ‘NPC’ in this game setup, looks like this:

They’re the same character! Except one is virtual, and one is a physical robot. Basically, what I was saying in that message was that it would be interesting if we had kids play the game with the virtual version of the robot, and an embodied version of the robot, where both versions have the exact same dialogue. That way, if kids who played with the embodied robot did significantly better than the kids who played with the virtual robot, we could attribute that solely to the fact that the robot was embodied, which was the only difference in those two conditions.

As it turned out, my grad student also thought that this was a big brain idea:

she’s saying here that often, in the field of human-robot interaction, the biggest criticism of saying that a robot has a beneficiary effect on something is that nobody actually compared that robot to a similar virtual agent, so it’s dubious to say that all the benefits were simply because you were using a robot

So now I had a cool angle for my paper!

Writing the Paper

For a paper like this one, where you create something and use it to run an experiment with certain conditions, these are the key sections that you wind up with:

- Abstract: the tl;dr of your paper, where you try to squeeze why you’re doing this study, what you found out, and why that’s important, all in < 200 words

- Introduction: you explain some context in the area you’re researching, what you’re going to be investigating in the paper, and a description of how you’re going to investigate it

- Literature Review: all the cool people who have done work similar to yours; your research is standing on the backs of giants!

- Experimental Design: describe the system components of the experiment and how they’re going to work together

- Study Design: your hypotheses, and where you’re going to recruit people from (and how many), and how you’re going to split them into study conditions, run the study, and evaluate their results

- Results: using your evaluation metrics, dive into the hard data you got and make pretty graphs

- Discussion: what you found interesting from the results, and whether or not you proved your hypotheses

- Limitations: possible confounding factors that could have affected your results, or things that you didn’t quite get to

- Conclusion and Future Work: you end on why your work is important, and what you’re going to be doing in the future

I’m in the process of writing a few more papers right now, and I can affirm that the only parts that I truly feel confident in writing are the first three. The rest is ~real science~ that I still feel marginally incompetent at. I particularly struggled at coming up with evaluation metrics, because if it seems like creativity is a hard thing to measure empirically – you’d be right!

One section that I notably did not have in my paper were results. Does that sound important? Yes, it totally does. But because of COVID-19, my ability to run an in-person study where kids play this game I made with a real physical robot has vanished; MIT isn’t allowing in-person studies allowing kids yet. We’re still trying to figure that one out. But anyways, if you think that the results section is the most important part of the paper…well, you’re right, but there are lots of different ways that you can talk about your work at a conference!

Conferences

Disclaimer: Nobody has actually formally given me an explanation of the research ecosystem, so everything I say is just from my own experience :P

From what I have gleaned, conferences are basically places where you gather with a bunch of people who do similar research to yours and you all talk about it and learn from each other. It’s really interesting to know the kinds of research people are doing in your field, and the benefit of conferences is that you get to talk to them directly about it. Then, when you’re working on your next research project, you might remember that cool person from the last conference you went to who had done some interesting research that you could refer to, and cite them in your paper. Research from conferences gets published in conference proceedings, a lot of which are available online! I learned (very) recently that you can just look up “[conference name][year] proceedings” and get an entire list of research published at that conference, which is pretty dope.

There are also lots of different ‘tracks’ that conferences have to encourage diversity of research. For example – my research didn’t have any results yet, but I was able to submit it to the ‘work in progress’ track so that I got to share my ideas and study design with the research community. The typical track that most people submit to is the ‘full paper’ track, which are papers that usually have a study that yielded results with a novel contribution to the field. When you read conference papers, most of the ones you read will be full papers. Other common tracks are student research tracks (which are specifically targeted at undergrads), or tracks specific to a certain theme.

Submitting a paper to a conference was honestly mildly reminiscent of submitting my college app essays. There are *very* strict page limits, and certain formatting or syntax errors can get you auto-rejected because conference reviewers don’t have time to try to fix your mistakes. I also had to make a video submission explaining the *entire* project in two minutes, which was…stressful. Plus, I had to record very precise demo videos of the game that showcased all of the different mechanics, which took forever. Although I tried to not have it come down to the deadline…it came right down to the deadline.

Getting accepted to the conference was also its own beast (although, naturally, I was pretty psyched to get in). The reviewers leave comments and suggestions for you to update for the final paper, which is referred to as ‘camera-ready’. I love this phrasing, because it makes me feel like I was dressing up the paper for a photoshoot or something. There’s also a lot of specific nonsense involved in making the submission camera ready – subtitling your video, making sure all of the images are greyscale (sad) and a certain PPI value, getting rid of the watermark in the draft, and trying to fit those extra words your reviewers suggested without going over the page limit…

Attending the Conference

Now obviously, if this were the correct timeline, I would have been able to attend this conference in person in Ottawa, Canada. But because we’re in the trashfire timeline, I attended this conference online. It was shockingly unjanky; the conference chairs used a platform called Whova and I basically got to set up a little virtual ‘booth’ where people would visit when it was my block of presentation time. Papers were streamed in sessions based on what topic they fell under, and you basically just visited a Zoom room, watched the authors present, and got to ask them questions afterwards. It was all very smooth.

The one unfortunate thing about a virtual conference is that I wasn’t fully committed to it – because I’m not physically at the conference, I would sometimes tend towards doing work rather than actually attending some of the presentations, which is unfortunate. I probably could have got a lot more out of an in person conference, and networked a lot more with fellow researchers. I’ll keep my fingers crossed for the future.

That being said, there were a lot of super cool papers, and I now follow a bunch of cool researchers on Twitter. Here are some of the papers I found the coolest:

- A Universe Inside the MRI Scanner: An In-Bore Virtual Reality Game for Children

to Reduce Anxiety and Stress - A Cheating Mood: The Emotional and Psychological Benefits of Cheating

in Single-Player Games - HexArcade: Predicting Hexad User Types By Using Gameful Applications

- I Don’t Care as Long as It’s Good: Player Preferences for Real-Time

and Turn-Based Combat Systems in Computer RPGs - Can Children Emulate a Robotic Non-Player Character’s Figural Creativity?

As a long time gaming nerd, and also as just a nerd, seeing research about games is REALLY COOL. I really enjoyed seeing the work other researchers are doing, and it made me think about what sort of research I’d like to pursue myself if/when I go back to grad school someday.

Still Learning

I am still a baby researcher and I have a lot to learn. I haven’t been cited yet,03 Hopefully I will be cited someday so I have no idea how the math around citations works. I still don’t quite understand why publishing in journals is more *prestigious* than publishing at a conference, and journal impact factors. I’m still learning how to write up data analyses and say coherent words about the numbers that I see. I still need to practice the scientific method and learn how to come up with good hypotheses.

But I’m excited to learn, and until I start my full time job in June, I’ll be a researcher in my lab pretty much full time. And sometime in the future, when I feel ready to go to school again, I’ll be back at it in the research world with all the skills that I gained with the undying support of my graduate student mentors.

The next conference I’ll be heading to is EAAI-21 with a team from my lab that I got to develop some really cool learning materials with, and teach them to real actual kids! We wrote a truly slapping paper that we’re excited to share with the world. I’m super excited to keep learning and growing as a researcher, and getting the opportunity to marvel at all the cool things people are doing around me – and hopefully contributing one or two cool things along the way myself.

- Google Can Children Learn Creativity from a Social Robot? for a representative example back to text ↑

- There are lots of roles that a non-player character can take; a peer, a supporter, an opponent, a navigator, etc. I had been referring to Autotutor and Family: A Review of Seventeen Years of Natural Language Tutoring back to text ↑

- Hopefully I will be cited someday back to text ↑